Stuck as “it” in a game of hide-and-seek, I grow old

Who shall I seek at the village festival

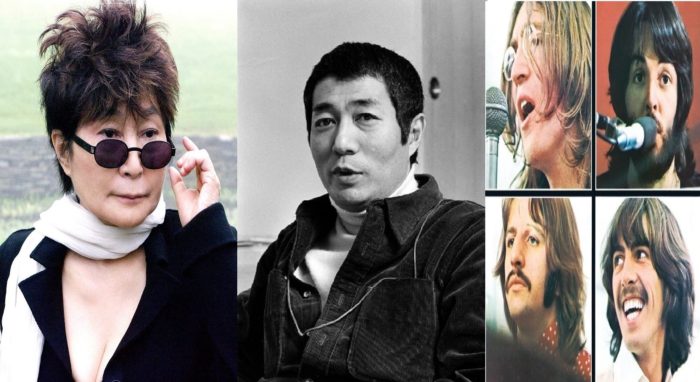

From the tanka poetry collection To Die in the Country, by Shuji Terayama.

Hide-And-Seek Piece

Hide until everyone goes home

Hide until everyone forgets about you

Hide until everyone dies

From Grapefruit, by Yoko Ono.

***

The children’s game of hide-and-seek was one of Terayama’s obsessions. Echoing the traumas of his childhood, he imagined a seeker (the oni, or devil, in the Japanese version of the game) who would never find the hiders. Abandoned and ostracized, he would have to carry on seeking them for the rest of his life..

Yoko is a hider. She knows you can win the game by a) finding the best hiding place, b) outliving all the other players.

Which is, more or less, what she has done.

***

Yoko Ono and Shuji Terayama were born just two years apart, in 1933 and 1935 respectively, but their circumstances could hardly have been more different.

Yoko was a member of the Yasuda clan which controlled the Yasuda zaibatsu (industrial group). Her family was highly international, her father being a senior banker with the Yokohama Specie Bank, which handled foreign exchange transactions in the pre-war era. Yoko moved to San Francisco at the age of two, then to New York in 1940, before returning to Japan as the storm clouds of war gathered.

In Tokyo, she lived in the exclusive Azabu district and was educated at Gakushuin, the Eton of Japan, where the future Emperor Akihito was her classmate. In 1951, she became the first female philosophy undergraduate at Gakushuin University, studying Heidegger and Kierkegaard.

After the economic reforms imposed by the Occupation authorities, the Yasuda family no longer controlled the Yasuda industrial group, but nonetheless they were very comfortably off. Yoko could do what she wanted – which was to attend college in New York, where her parents had re-established themselves, and get involved with the burgeoning avant garde in its new global capital.

In stark contrast, Shuji Terayama came from one of the poorest and most remote parts of Japan. He liked to claim that he was born aboard a moving train and thus had no hometown. In reality, he was born in Hirosaki, a market town in Aomori Prefecture, in the far north of Honshu, Japan’s main island.

Even in the 1960s, Aomori was a twenty hour train ride away from Tokyo. Throughout his career, Terayama deliberately stressed his local accent which he considered a badge of authenticity, in contrast to the lifeless language of authority that was standard Japanese..

Terayama’s father was a policeman who died of disease in South East Asia after being conscripted into the Japanese army. Terayama and his mother were burnt out of house and home by the American air-raids of July 1945.

After the end of the war, Terayama’s mother went to work as a cleaner on the American airbase in nearby Misawa. Then, when he was thirteen years old, she moved to an American base in far distant Kyushu, leaving him in the care of a relative who operated a cinema.

Japan’s war destroyed Terayama’s family and almost killed him. He also personally experienced the stunning reversal of values that followed – in a few months the Americans went from hated enemy to his mother’s economic lifeline.

What had seemed to be solid reality (Japanese Imperialism, Emperor-worship, martial virtues) suddenly melted away like a bad dream. In its place a totally different reality (democracy, pacifism, equality) had appeared.

Or was that a fiction too?

Yoko’s war experience was much less visceral. Upscale Azabu, where her family lived, was never bombed. In the later stages of the war they fled to the comparative comfort of Karuizawa, a picturesque town in the foot-hills of the Japanese Alps which served as a summer getaway for Tokyo’s high society. Yet her civilian father was absent too – stationed in Vietnam, then interned there.

Even in Karuizawa, where Yoko was to holiday with John Lennon in the 1970s, food was hard to come by. Yoko’s aristocratic mother was reduced to bartering foreign-made household implements for supplies of rice. When her younger brother complained of hunger, the pre-teen Yoko would get him to “imagine” a lavish meal for them both to eat.

This prefigured the Imagine instruction pieces in Grapefruit and, indeed, the song Imagine itself, which is now credited to “Lennon-Ono.”

The annihilative destruction of modern war can have powerful cultural consequences, sweeping away pre-existing values and ushering in new artistic movements – such as surrealism, Dada and literary modernism after the First World War.

A similar current swept through Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, taking inspiration from the original European avant garde and native traditions, and adding post-war inventions such as ankoku butoh (“the dance of darkness”).

When reality collapses, imaginary worlds suddenly seem more dependable.

To be continued.