Published in Nikkei Asia 23/11/2020

Can you imagine best-selling novelist Haruki Murakami leading a coup attempt against Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga? Or Booker Prize winner Ian McEwan taking a top general hostage in a British army base and inciting a rebellion against Boris Johnson’s government? Or any of the legions of writers and artists who regularly hammered President Donald Trump on social media choosing to die for their cause?

Probably not, but that would be the modern equivalent of what happened on Nov. 25, 1970, when the brilliant Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima and four accomplices invaded the office of the commander of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, called on his troops to topple the government of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, and then committed seppuku, or ritual disembowelment (vulgarly known as hara-kiri).

Mishima had been nominated three times for the Nobel Prize for Literature, but he was not just a writer. He was a major celebrity in Japan, the first to be described as a supasuta (superstar) by the media, and one of the best-known Japanese writers abroad. In the late 1960s the magazine Heibon Punch nominated him the “coolest male” in Japan in its “Mr. Dandy” awards, ahead of movie star Toshiro Mifune and baseball hero Shigeo Nagashima.

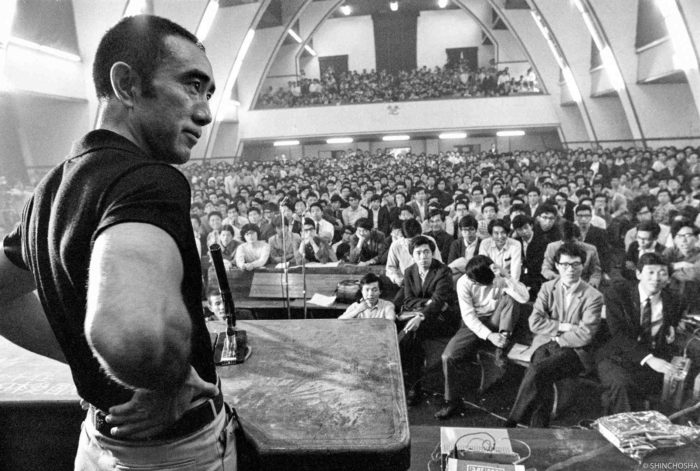

Since his shocking suicide, establishment Japan has preferred not to dwell on the “Mishima incident,” and only ultra-rightwing groups have seemed happy to mark the various anniversaries of his death. For the 50th anniversary, though, the vibe has been different. A few days ago, I managed to catch Mishima: The Last Debate, a documentary that uses recently discovered footage of a face-off between Mishima and hundreds of radical students during violent street protests in 1969.

The film was released in March, but was still screening in Tokyo’s central Shibuya district. I half-expected the audience to be dominated by elderly rightists in combat gear. I was wrong. There were women in their 20s and 30s wearing designer masks, some students, ordinary looking couples and solitary intellectual types. Although the film was advertised as a tense confrontation between violence-prone right and violence left-wing groups, the debate was mostly respectful on both sides, with Mishima’s wit drawing gales of laughter from the students and, indeed, the cinema audience.

Other films about Mishima have been made this century. The late Koji Wakamatsu, a radical left sympathizer once known as the “Kurosawa of pink [erotic] movies,” directed 11.25: The Day He Chose His Own Fate (2012). This biopic offers a straightforward factual account of Mishima’s last months. There is also a film version of Spring Snow, the first and best volume in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy.

His books are still popular too. Mishima wrote intense, heavyweight novels conveying his philosophical ideas, but also less serious fare as entertainments for the mass market. Interestingly it is the latter that have been doing particularly well these days. A light novel called Yukio Mishima’s Letter Writing Class has consistently ranked in Amazon Japan’s Top 10 for Japanese literature. Another entertainment called Life for Sale was the top seller of 2016 in the Japanese literature department of Kinokuniya, Japan’s largest bookshop, with total sales topping 250,000.

At least 30 novels and essays have been translated into English, including Life for Sale. There are also two more biographies. Persona is a meticulously researched doorstopper by Naoki Inose, novelist and ex-governor of Tokyo, and Hiroaki Sato. Yukio Mishima is by British author Damian Flanagan.

Another British Mishima enthusiast was the rock star David Bowie, who appears to have planned his own death in 2016 with Mishima-like artistic precision. Bowie painted a portrait of Mishima, which he hung on the wall of his Berlin apartment in the late 1970s. In the 1990s, he bought a bronze bust of Mishima by British sculptor Sir Eduardo Paolozzi at Sotheby’s. More recently, he referred to the opening of Spring Snow in his 2013 album The Next Day: “Then we saw Mishima’s dog / Trapped between the rocks / Blocking the waterfall.”

The accent on the lighter, more humorous side of Mishima may have contributed to what seems to be a subconscious reassessment within Japan. There is also the fact that some of his political stances — on validating the constitutional status of the Self-Defense Forces, on protecting Japan’s traditional culture — no longer seem extreme.

Another impression came to me forcefully while watching the debate between Mishima and the radical students who were occupying the Tokyo University lecture hall. The cinema audience was agog at the huge moral issues that were being argued in a way that could never happen in today’s world.

In his much-misunderstood book, The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama uses the ideas of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche to speculate about what kind of landscape the post-historical “last men” will inhabit, once liberal democracy has triumphed everywhere. The answer is a world devoid of great art, struggle, risk, wisdom and self-knowledge. The last men, Fukuyama posits, “will be concerned above all for personal health and safety … content to sit at home congratulating themselves on their own broadmindedness and lack of fanaticism.”

Mishima’s dislike of Anglo-Saxon liberal democracy came from Nietzsche. According to Flanagan, “Mishima’s bond with Nietzsche was described by Mishima’s father after his son’s death as of an intensity beyond imagination.”

Mishima committed seppuku just 25 years after the end of World War II, much too soon for him to escape being dismissed as an unbalanced reactionary throwback to the age of militarism. Fifty years on, the last man is here, placidly enjoying his lockdown thanks to Zoom, Netflix and Uber Eats, totally comfortable with the prospect of a future controlled by artificial intelligence and big data.

Perhaps we need a Mishima to shock us out of our complacency.