Published in Japan Forward 10/11/2022

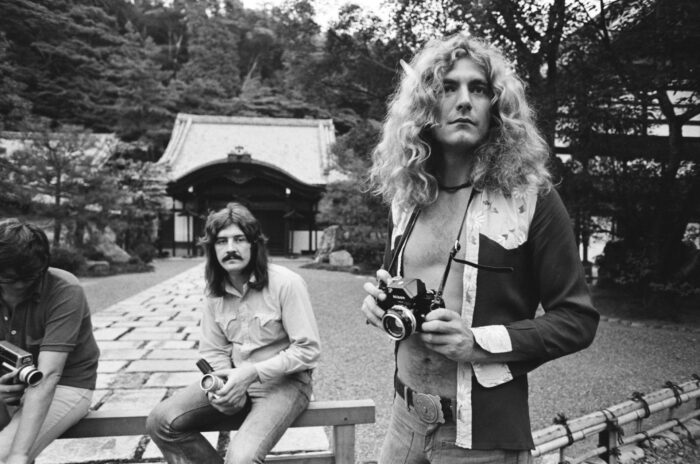

On their first tour of Japan in 1971, hard rock maestros Led Zeppelin came up with a generous gesture. In addition to their scheduled concerts in Tokyo and Osaka, they decided to add a benefit performance in Hiroshima.

The event was a success, with vocalist Robert Plant giving a moving speech about the healing power of music and seven million yen (about $150,000 in today’s money) being raised for the victims of the atom bomb.

Later in Osaka, drummer John Bonham, a heavy drinker with a violent streak, ran wild with a samurai sword he had bought, slashing everything in his suite to ribbons including pillars and decorative scrolls. The damage: seven million yen.

This anecdote encapsulates the contradictions and absurdities that surround the encounter between Western rockers and modern Japan, as described by author Chrisopher Keaveney in his book Western Rock Artists, Madame Butterfly and the Allure of Japan.

The intellectual key he uses is “orientalism”, cultural critic Edward Said’s term for the depiction of eastern cultures as exotic, alien and inferior. The template is Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly, which tells the tale of a relationship between Lieutenant Pinkerton of the U.S. Navy and a young geisha in Nagasaki.

Keaveney is an Assistant Professor at Rikkyo University, but also an ardent fan of “the golden era of album rock” who played in several cover bands himself. A barometer of his musical taste is that he describes Cheap Trick Live at the Budokan as a “legendary” album and reveals that his first live rock show was Queen in New York in 1977.

It is fair to say that there is a tension between his obvious love of this brash, unruly music and the contemporary academic’s sensitivities to gender, race and power relations.

Does Deep Purple’s Woman from Tokyo really “draw liberally from conventional orientalist expectations of the geisha figure”? This is Deep Purple we are talking about here! Their best-known song is about a Swiss chateau burning to the ground. Another famous number of theirs compares a girlfriend’s physical attributes to those of a high-performance sports car.

In comparison, Woman from Tokyo – recorded before the band had ever visited Japan – is rather sweet.

Rising from the neon gloom

Shining like a crazy moon

Yeah, she turns me on like a fire

I get high

My woman from Toh-kee-O

She makes me see

My woman from Toh-kee-O

She’s so good to me

So influential was the song that most foreign bands have followed the three syllable pronunciation of Tokyo, as did J-pop megastar Kenji Sawada in his 1980 hit song Tokio.

Probably the first meeting of modern rock and modern Japan occurred in 1965 when a young Japanese music journalist called Rumiko Hoshika showed up at the Abbey Road studios in London where the Beatles were recording the Rubber Soul LP.

She won the band’s full attention because she was wearing a brightly coloured kimono. She had the full attention of Brian Epstein, their gay manager, because she had brought him a samurai sword and he was a major fan of the films of Akira Kurosawa.

In the world of cultural studies, this is known as “self-orientalism” and is considered rather disgraceful. Keaveney goes as far as to say that Japanese people themselves are “complicit in the construction of Orientalism” if they offer a western visitor an unusual regional cuisine or a traditional souvenir like an uchiwa fan.

Back in the real world, Hoshika’s gambit worked wonders. Her meeting with the Fab Four went on for three hours and she was to interview them every year until the band broke up. She is still going strong today, hosting all kinds of Beatles events.

Keaveney does dig up some unpleasant and borderline racist material from a Swiss heavy metal band, as well as cliché-ridden stuff from 10cc and some forgettable British “new wave” bands of the 1980s. More valuable is his commentary on Styx’s song Mr. Roboto, with its Japanese language opening and super-catchy refrain of “domo arigato, Mr. Roboto”.

“For a Western audience,” Keaveney notes, “Mr. Roboto, a song about the cold efficiency of robots in a dystopian future and the association between this future and Japan, had a particular resonance. It is hard now to imagine the sense of anxiety, approaching, panic produced by Japan and felt in the West as Japan’s economic might steadily grew in the 1980s.”

Indeed. A year after the song was released in 1981, a Chinese-American man was beaten to death in Detroit by two auto workers who mistook him for a Japanese. This kind of paranoid Japan-bashing rock seems a good deal more objectionable than Deep Purple’s “Fly into the rising sun / Faces smiling everyone.”

It is a pity that the author did not spend more time on David Bowie, a long-time Japanophile with a particular interest in Yukio Mishima. During his stint in Berlin, Bowie painted a portrait of Mishima and in the 1990s acquired Sir Eduard Palozzi’s bronze bust of the Japanese novelist at Sotheby’s. In his 2013 album The Next Day, Bowie referenced an episode from Mishima’s novel, Spring Snow.

Then we saw Mishima’s dog

Trapped between the rocks

Blocking the waterfall

David Bowie’s Japan was very different to Deep Purple’s, let alone Styx’s.

Likewise, rather than dwelling on obscure or boring artists, Keaveney could have analysed Japan-related songs by more interesting songwriters such as Nick Lowe’s Gaijin Man or Elvis Costello’s Tokyo Storm Warning. Then there are these curious lines in Bob Dylan’s Tight Connection to My Heart –

Madame Butterfly, she lulled me to sleep

In a town without pity where the waters run deep

She said be easy, baby

There ain’t nothin’ worth stealin’ round here

The rest of the song has nothing to do with Japan, but the associated music video plays amusingly with Orientalist fantasies. Shot in pre-bubble Tokyo, the story, insofar as there is one, has Dylan being busted for drug possession by singing policemen (perhaps a nod to Paul McCartney’s arrest at Narita Airport a few years before), then wandering around the Roppongi entertainment district.

There, the future Nobel laureate finds himself torn between a jealous America girlfriend and a mysterious Japanese beauty, played by Mitsuko Baisho. Unwilling to take sides, he seems to end up with both. Why didn’t Lieutenant Pinkerton think of that?

The book’s final chapters take us into the twenty first century, where rock has been dethroned by other musical genres like rap and pop and the market for CDs has collapsed. The two phenomena are linked since rock, with its thunder and theatrics, is ill-suited to streaming, which is for people to listen to while doing something else.

Japan’s image has changed too. Instead of Kurosawa movies and Zen temples, it’s all about anime, monster movies and cosplay. Contemporary rock band The Flaming Lips captured the zeitgeist brilliantly with their album Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots and elaborate live stage show.

Needless to say, there is no more running naked through hotel lobbies or wielding of samurai swords. The new breed of artist has to be super-sensitive to the ethical dimension of everything said and done or face the wrath of the social media police.

Keaveney’s hero is Rivers Cuomo, frontman of the band Weezer. In the 1996 album Pinkerton he gives a guilt-ridden account of dysfunctional relationships, struggles with identity and loneliness and likens himself to the “asshole America sailor” of Puccini’s opera.

On the other hand, Keaveney takes pop stars Gwen Stefani and Avril Lavigne to task for “cultural appropriation” in their Japan-themed music videos, echoing the condemnation of Asian-American activists at the time. Yet there was never any criticism of Harajuku Girls and Hello Kitty in Japan itself. Indeed, the songs were well received by the Japanese public, a fact that Keaveney finds perplexing and disappointing.

“One of the abiding ironies of criticisms in the West of the Orientalist representations of Japan by Western artists is how rarely Japanese traditionally have taken offense,” he comments. “What are seen as acts of inappropriate racial appropriation and stereotyping in the West often have been regarded by the Japanese as flattering.”

When Keaveney mentions the West, he really means the United States and the sliver of its population that obsesses about such issues. As for so-called “cultural appropriation”, that has been Japanese national strategy for the last 170 years.

Japan has also appropriated Led Zeppelin. Drummer John Bonham, who died of alcohol poisoning in 1980, was nobody’s idea of a role model, but the band is much loved in Japan, despite his appalling behaviour. Numerous tribute bands keep Zeppelin’s legacy alive, with the oldest, Cinnamon, now in its fiftieth year.

There is even a piano trio made up of top-notch Japanese jazz musicians which plays the music of Led Zeppelin and nothing else.

It’s unlikely that Weezer, or Gwen Stefani or Avril Lavigne or any other contemporary artist, will be attracting a similar following fifty years on.