Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 5/9/ 2014

Is Abenomics a busted flush? You might think so from the splurge of negativity in the domestic and foreign media. Tabloid headlines blast Prime Minister Abe on a daily basis while overseas commentators announce the death of his “voodoo economics.”

There’s no smoke without a fire. Recent data have been poor, notably the awful print for second quarter GDP. There have been policy missteps, some excusable, some less so. As a result the Abe administration’s poll ratings have fallen from the stratospheric to the merely high. The recent underwhelming cabinet reshuffle is an attempt to regain momentum, but the effect is unlikely to be lasting.

Even so, the achievements of Abenomics are real and tangible. Since Prime Minister Abe took office in December 2012, employment has risen by one million to 63.5 million. Job openings are the most plentiful in two decades. In 2013 the Tokyo stock market had its best year since 1971 – adding a trillion dollars to the national wealth. Dearer to the hearts of home-owners are real estate prices, which are also on the move, thus relieving the curse of negative equity. Meanwhile foreign travelers have been flooding into Japan, putting the tourism account in the balance of payments into the black for the first time since 1969.

Crucially, the new regime at the Bank of Japan has succeeded in raising both actual inflation and inflationary expectations. Now real interest rates are negative for the first time since Japan’s economic bubble imploded a quarter of a century ago. Slowly but surely the balance of advantage is shifting from the risk-averse to risk-takers.

Why then the sudden bout of summertime blues? There are two main reasons. First the Abe government underestimated structural factors that make the work of reflation more difficult, but are ultimately signs of positive change.

Exports have flat-lined despite the weaker yen because Japanese companies have become more competitive, not less. Having shifted production of low value added items off-shore, managements no longer need to slash prices to secure market share. Instead they can simply reap the fatter profit margins – which is good for stock prices, but bad for economic activity.

Likewise the tight labour market has yet to translate into substantial wage gains because participation – mainly part-time and female – is soaring. In other words the labour market has become more flexible. A Japanese woman aged between 25 and 54 is now more likely to have a job than an American woman of the same age or a Spanish male.

The second factor was a straightforward policy blunder. This spring Mr. Abe pushed through a 3% hike in the consumption tax on the recommendation of his financial bureaucrats, the rating agencies, the IMF and several prestigious overseas publications. How could such experts be wrong? Quite easily – in fact their track record has been consistently dismal. Tax revenues are now running lower than a year ago.

Mr. Abe should use fiscal policy to stimulate final demand, not crush it. One idea would be to copy the South Korean plan of taxing excess corporate cashflow, thus incentivizing managements to use the money on wages, investment and dividend payments.

The BoJ will need to do more too. Both the US and the UK had to implement several rounds of quantitative easing. Critics claimed there would be no effect or alternatively that hyper-inflation was on the way. Not coincidentally, though, these are the developed countries with the best growth profiles today.

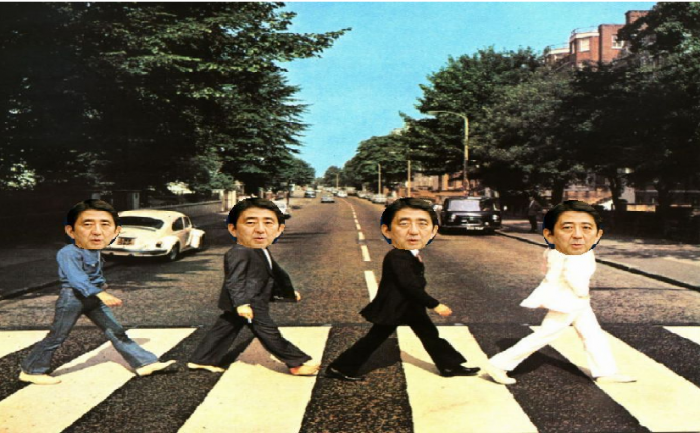

Abe the Voodoo Chile

All in all Mr. Abe’s achievements overshadow the efforts of his predecessors, including the globally celebrated Junichiro Koizumi. His greatest failing so far is not that he has been too extreme, but that he has been too respectful of the consensus. The recent reshuffle, with its doling out of key posts to bigwigs from the party factions, is another indicator of this tendency.

What Mr. Abe needs to do is recover his original radicalism. He needs to redouble his efforts to revive the economy, overruling his timorous officials where necessary. Instead of “re-interpreting” the pacifist constitution to allow a more active Japanese military, as has been done many times before, he should kick off a formal process of constitutional reform.

Then when the stock market is well into its next bull run and the streets are a-buzz with the feel-good factor, he should call a snap ”love me or leave me” general election, just as Junichiro Koizumi did in 2005. But unlike the eccentric Mr. Koizumi, he should serve the additional term and turn the promises into policies, thus cementing his status as a transformational leader.

Criticism is to be expected, especially when the policy focus expands from economic revival, a goal which commands broad support, to include more contentious issues of security policy. But it would be weak leadership to leave such serious matters unaddressed. Some of Mr. Abe’s hardcore foes are against the very idea of a self-confident Japan playing an active regional role. In response he can point to his recent summit with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a vindication of his strategic vision.

As for voodoo economics, contrary to the depiction in Hollywood B-movies, voodoo is a complex spiritual system that encompasses many areas of human experience. There’s no reason why economic activity should not be included. Keynes emphasized “animal spirits” and monetary theorists talk about moulding expectations. “Strong spirits” happens to be the Japanese term for bullishness. Inducing that psychology is vital to Mr. Abe’s further success.