Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 2/5/2016

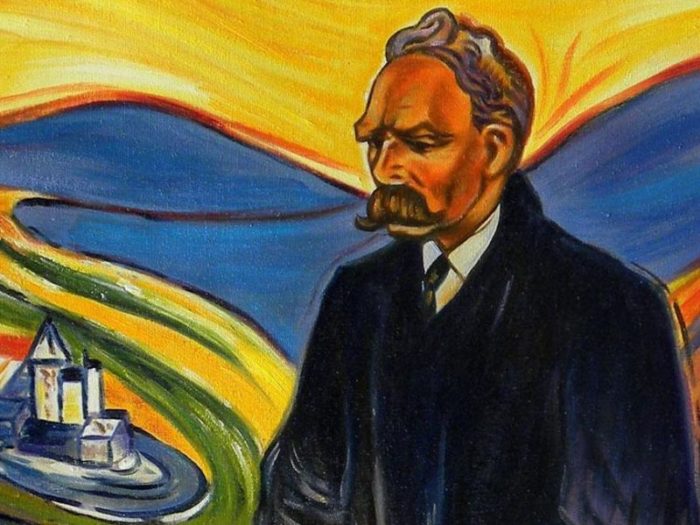

That which does not kill us makes us stronger, as German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once famously observed. The precept could be applied to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s policy agenda. Recent months have seen a series of setbacks and disappointments for the inventor of Abenomics. But if a clear-headed appraisal is made of what went wrong, there is every chance that flagging confidence in his leadership can be restored and indeed strengthened.

For the first three years of his tenure Abe had fortune on his side, but now reality has become much less co-operative. A symbolic event was Japan’s surprise loss in the bidding competition for Australia’s next generation of submarines, a megadeal worth $50 billion.

Most observers believed that Japan’s offering was technically superior, but after Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull ousted his strongly pro-Japanese predecessor Tony Abbott, Japan’s Soryu-class submarine went from favorite to bottom of the class. It was France that won the bid.

The Global Times, the English-language mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, was in no doubt about the geopolitical implications. In an article headlined “Canberra submarine deal tilts security balance,” it crowed “Australia is different from Japan. The former is more willing to show its effort of balance between China and the U.S., while the latter boasts of its partiality to the U.S.”

BE MORE FRENCH

Whatever the reasons behind the Australian volte-face, it seems likely that Japan invested too much in the personal relationship between Abe and Abbott and paid insufficient attention to the non-technical aspects of the deal, including the willingness to share technology and meet Canberra’s other requirements. In contrast, the French are past masters in navigating the murky waters of the global arms trade.

Until now the Japanese defense industry has been an example of the “Galapagos syndrome,” whereby products evolve in an insular domestic market that leaves them ill-suited to global standards. The major companies that supply Japan’s Self-Defense Forces are in varying degrees of disarray as their other business lines have become chronically unprofitable. Without the improved scale that export markets bring, they are likely to fall further behind global competitors, with implications for Japan’s long-term security.

Abe was right to break the taboo on arms exports – which never had any legal foundation – and provide governmental support to the defense industry as many other countries do. But defense technology cannot be sold just on price and quality, like cars or cameras. There are other requirements that must be satisfied and other incentives that can be brought to bear. The commitment to success must be total, as France clearly understood. If Japan takes this on board, it still can become a significant player.

KURODA’S ZEN MOMENT

Financial markets are proving similarly unhelpful. Specifically, the yen has soared from 125 to the U.S. dollar nearly a year ago to a recent high of 106, taking stock prices down by 25% and stymieing the reflationary dynamic that is at the core of Abe’s economic program. A sharply rising currency amounts to a tightening of financial conditions, the opposite of what is required in a slow growth, deflationary world.

Corporate profits are already suffering and both the inbound tourism boom and prospects of “re-shoring” Japanese production from overseas will be hurt by the loss of competitiveness that the resurgent yen has wrought.

Ironically, the once popular disaster scenario for Japan – dubbed Abe-geddon by the chief investment officer of UBS Wealth Management – predicted a collapse in the yen and an explosive surge in bond yields as the country “went bankrupt.” What we have now is the reverse. The yen rises because it is considered a “safe haven” while the yield on Japan’s 10-year government bonds has fallen below zero as institutional investors refuse to sell. Japan’s problem is that its credit is too good.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda was widely expected to respond to these events with new easing measures at the end of April. Instead, rather like a Zen master shattering the preconceptions of his acolytes, he shocked the markets by doing precisely nothing.

This was fully in character. Every change in monetary policy that Kuroda has enacted so far has come as a surprise to the market and probably the next will be no different. He still has plenty of cards to play – including increased purchases of bonds and exchange traded funds, and offering loans to the banking system at negative interest rates.

Kuroda’s decision not to act this time may have been intended as a way of allowing space for new fiscal initiatives to emerge. It is clear that there are diminishing returns to monetary policy in Japan as in the rest of the world. Monetary easing is likely to have much more economic impact if coupled with an easing of fiscal policy, instead of acting as a counterweight to fiscal tightening.

Financing should not be a problem. The Japanese government could follow Ireland and Belgium in floating 100-year bonds, with a coupon of below 1% being quite feasible.

The BoJ has stated that it is still gauging the effects of negative policy rates introduced in January. And indeed the recent survey of loan officers’ views reveals a significant rise in credit demand from households. Yet such improvement is likely to be overwhelmed by the violent moves in financial markets.

Economic policymakers cannot afford to wait much longer. They need to retake control, with the G7 summit Japan is hosting at the end of May providing a perfect stage for new inititiatives.

T.I.N.A. (THERE IS NO ALTERNATIVE)

There is no question that Abe has achieved major economic successes. Last year saw the best growth in Japan’s nominal gross domestic product in 20 years and the public debt to GDP ratio fell for the first time since 1991. Among the 34 members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Japan’s “misery index” (the sum of the unemployment rate and the inflation rate) is bettered only by that of Switzerland.

Politically, Abe still holds the strong cards too. According to a recent Tokyo Broadcasting System poll, even the national security legislation that proved so contentious nearly a year ago is now supported by 45% of the public, compared to 34% who oppose the laws. Yet he cannot afford to let the absence of credible opposition lead to complacency and failure to address obvious weaknesses.

In the case of the submarine deal, what is needed is an objective review of what went wrong and a commitment to do whatever it takes to ensure Japan wins next time. In the case of macro-economic policy, monetary and fiscal measures need to be integrated and deployed for maximum reflationary effect. Tax hikes should be off the table for the foreseeable future.

The strategic logic of the Abe agenda remains intact. In fact “there is no alternative,” to quote a phrase associated with former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Plenty of time and opportunities remain for Shinzo “Tina” Abe to mould Japan’s future.