Published in Nikkei Asia 8/2/2023

Could videodiscs make a comeback one day, if only for a specialist audience? At first glance, it would seem an unlikely prospect. The streaming services offer you a huge variety of films to watch at low prices without the inconvenience of leaving your couch. Why bother to resuscitate a dying medium from the pre-internet era?

Yet, much the same could be said about vinyl records, which I collect myself, both second-hand copies of classic albums and the new releases that are becoming increasingly numerous. Why do I do it? Many vinyl fans would cite the sound quality, and indeed there is a night-and-day difference when compared with Spotify etc. But that is not all, or even the main reason for me.

More important is the connection with the physicality of the object – the artwork on the LP cover, the sleeve notes, the ritual placing of a shiny black disc on the turntable and watching it rotate. That’s all part of the experience. What’s more, the thing does not belong to some giant tech company that stores it in the form of bytes in a server farm in the middle of nowhere. It belongs to me, to lend to friends or do what I like with. It forms a tiny piece of my identity.

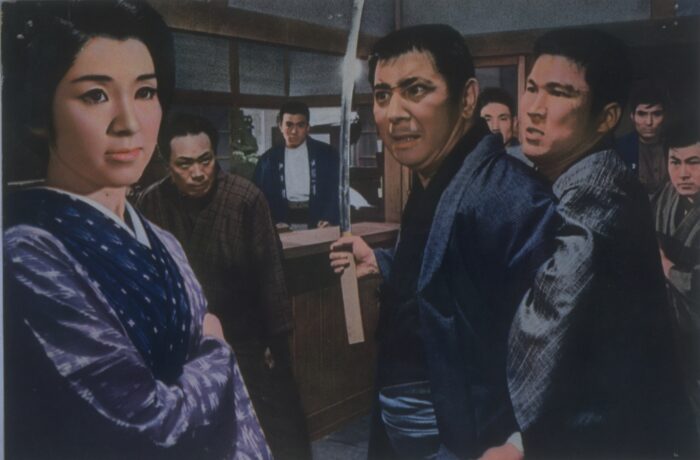

Such thoughts came to me after viewing “Big Time Gambling Boss” (1968; directed by Kosaku Yamashita), a yakuza movie recently released on Blu-Ray by UK company Radiance Films in a limited edition of 2,000 copies. Blu-Rays are similar to DVDs, but make use of superior technology. The retail price is not cheap at £16.99 ($22.99 from Amazon.com), but it’s worth every penny in my opinion.

Much care has been taken with the presentation, a key drawing point for the intended audience. The cover is reversible and features the original and newly created artwork. A 24-page booklet includes an essay by Stuart Galbraith IV, author of a magisterial double biography of Akira Kurosawa and star actor Toshiro Mifune, and a rundown of the main actors by freelance film writer Haley Scanlon.

There are more extras on the disc itself. Mark Schilling, long-time film critic for the Japan Times and author of several books on Japanese cinema, gives a video talk on the yakuza film genre. Punk rocker and Japanese cult film expert Chris D. goes into detail about the 10-film series of which “Big Time Gambling Boss” was the seventh to appear. All these contributions add value and help to put the film into context. New subtitles have been added and the visuals are pleasingly clean, thanks to the high-definition digital transfer.

This hard work would be in vain if the film were just another example of the “ninkyo” (chivalry) yakuza genre, hundreds of which were churned out in the nineteen sixties. Happily, that is far from the case. It is arguably one of the best yakuza films ever made.

Most of the “ninkyo” films are corny and sentimental, featuring implausibly noble gangster heroes. Later, in the 1970s, yakuza movies became more violent and realistic, as exemplified by the “Battles Without Honour and Humanity” series, directed by Kinji Fukasaku.

That era is justly celebrated as the heyday of the yakuza genre, yet the films, though gripping and superbly written and acted, never get close to the greatness of Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather series. Modern-day yakuza movies are generally over-reliant on Tarantino-esque shock tactics and end up no more realistic than the formulaic 1960s product.

What is missing is inner conflict and character development. “Big Time Gambling Boss” delivers that in spades, largely thanks to director Yamashita, script writer Kazuo Kasahara and leading actor Koji Tsuruta. Right from the opening scene, we are plunged into a moral dilemma, as the gambling clan is asked to join a united patriotic front of yakuza groups (the story is set in pre-war Japan) tasked with peddling drugs on the Asian continent. That is just a prelude to the unavoidable human tragedy that slowly builds momentum through the film, engulfing the main characters in desolation and disaster.

In his essay, Stuart Galbraith IV nails the source of the film’s power. “Yamashita confidently lets scenes play out in long static cuts, allowing his audience to focus their attentions on the unspoken thoughts of his characters.” This technique is common in the works of a master of subtilty like the great director Yasujiro Ozu. It is rare in yakuza movies.

Strangely, the film was not particularly successful on release. It was only when a rave review by novelist and right-wing provocateur Yukio Mishima appeared in a specialist film magazine that the cinema-going public sat up and took notice. More publicity was generated when Weekly Playboy (no connection with the U.S. magazine) published a dialogue between Tsuruta and Mishima in July 1969. Mishima was a long-standing fan of the handsome Tsuruta, who was just one month older than him, but, unlike the novelist, had served in the war.

A genuine tough guy, Tsuruta was famous for having stood up to real life yakuza on several occasions, displaying notable cool in the presence of Japan’s most fearsome gangster boss. Although he despised the war leaders and considered the kamikaze strategy a horrible idea, having himself “sent off” young pilots to their death from the airbase where he was stationed, he was almost as right-wing as Mishima in his own way.

In the dialogue, he agrees with many of Mishima’s criticisms of contemporary Japan, even declaring that he would get his sword ready if radical political action was planned. Mishima ended the conversation with an admiring “you are exactly the man I hoped you would be.”

The friendship continued, with Mishima inviting Tsuruta and his wife to dine to dinner on several occasions. But Mishima did not involve Tsuruta when he sensationally committed ritual suicide in the headquarters of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces in November 1970, having failed to persuade soldiers to back a coup d’état. When Tsuruta heard what had happened, he unsheathed his ceremonial sword and wept.

Yukio Mishima is not the only famous admirer of “Big Time Gambling Boss”. It has earned high praise from Paul Schrader, who wrote the script for Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” and directed a fine film about Mishima, amongst other achievements. But who would have known anything about this neglected classic if Radiance had not released it? Certainly not me.

So is the videodisc on its last legs as a medium, or does it have a future as a niche product like the vinyl record? The latter, I hope. And if so, Japan may well play a crucial role. For Japanese consumers never gave up on vinyl, even through the long ascendancy of CDs, when retailers like Disk Union served as an invaluable source of product and information. Meanwhile, Tower Records still exists in Japan and does a thriving trade, more than twenty years after every other branch in the world disappeared from the map.

Obsolescence is by no means inevitable, despite Big Tech’s ambition to own everything. There is always demand for a quality product, at least in Japan.