Published in Japan Forward 12/05/2023

“We’re not done investing in Japan yet.”

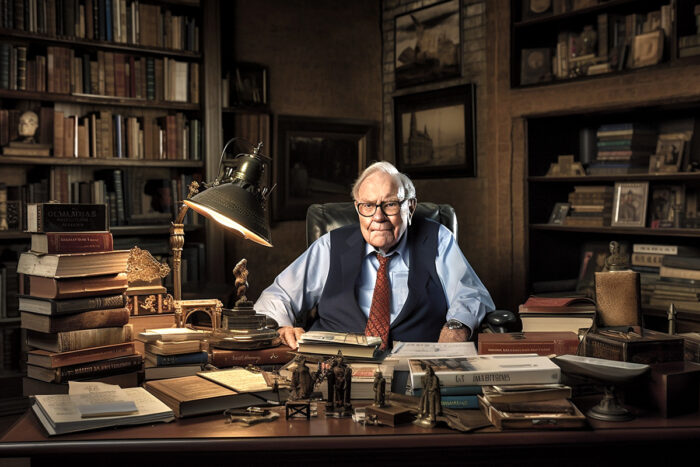

That was one of the headlines that came out of Warren Buffett’s recent annual shareholder’s meeting in Omaha. Coming shortly after his trip to Tokyo in April, it suggests that the great investor has become a long-term bull of Japan.

Now that Buffett has sold his position in Taiwan Semiconductor and is exiting Chinese electric vehicle company BYD, his investments in the big five Japanese trading houses constitute his only significant non-US positions.

So far, these have worked brilliantly for him. From his initial purchase in 2020, the stocks of Mitsubishi Corp, Itochu, Marubeni, Sumitomo Corp and Mitsui & Co. have soared to all-time highs and collectively more than doubled.

At the investment jamboree, Charlie Munger, Buffett’s 99-year old business partner, asked him to explain the rationale behind the purchases. He responded that it was a simple decision – the companies were “very substantial” in their operations and had been buying back shares and paying generous dividends.

In another interview, he declared that the wide range of their activity reminded of his own company, Berkshire Hathaway, and that he hoped to remain an investor in the trading houses for at least ten years. Buffett is now 92, but he took his designated successor, the 60 year old Greg Abel, with him to Tokyo. Abel described the trading houses as “fantastic investments” so there is no reason to doubt Berkshire Hathaway’s commitment.

Buffett is considered, for good reason, to be the most successful investor in history. If you’d put a thousand dollars into his company in 1980, you’d be sitting on more than $1.7 million today. He has accomplished this by patient long-term investment – his favoured holding period is “forever” – based on solid value principles.

People pay close attention to his comments, and he knows it. The event in Omaha was attended by an audience of 40,000 and was broadcast in its entirety on CNBC. So it is interesting to see the effusive remarks he has made about these companies and Japan itself. When asked about the timing of the recent trip, he answered as follows.

“It has nothing to do with whether we think the stock market is going to go up or down next year, three years from now or five years from now. But you have a very strong feeling that Japan, 20 years from now, 50 years from now, and the United States 20 years from now, they will be bigger. And we feel that these five companies are a cross section of not only Japan but the world.”

This is quite a counter-intuitive call. Pessimism is the default mode for many observers of Japan, who cite the aging population, insufficient entrepreneurship, lack of opportunity for women etc. etc. etc. But Buffett didn’t become the fifth richest man in the world by following the conventional wisdom.

We know that he has recently become sensitive to geopolitical issues because he cited them when Berkshire Hathaway, very uncharacteristically, dumped the stock of Taiwan Semiconductor just a few weeks after making the initial purchase. The likelihood is that one of Buffett’s team made the investment on fundamental grounds but Buffett himself considered the geopolitical risks too high and recommended a speedy exit.

At the Omaha event, Charlie Munger deplored the breakdown in relations between the United States and China, laying blame on both sides “for being stupid”. Buffett, ever the realist, declared “we’re just at the beginning of this, unfortunately.”

Could it be that Buffett sees a more cosmopolitan Japan filling a crucial new role, part technological, part diplomatic, part military, part cultural, in this divided world? A Japan that is the antithesis of Xi Jinping’s China, that attracts investment and people, that has its own sphere of influence?

That’s not how Buffett felt twelve years ago when he made his first visit to Japan. Then he was reviewing the tsunami damage at the Japanese subsidiary of an Israeli company that he had recently bought in a private equity deal. He offered plenty of sympathy and praise for Japan’s response to the devastating natural disaster of March 2011, but what he did not do was make any investments.

Why would he? At the time, the corporate confidence indicator was stuck in negative territory, where it had been for most of the previous 15 years, and profitability was fragile. Not helping at all were an overvalued currency of 80 yen to the dollar and a deflationary mindset instilled by hard money advocates in the central bank. Small wonder the Nikkei Index was no higher in 2012 than it had been in 1983.

All that changed under the aegis of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe who whose reflationary agenda immediately improved corporate margins and animal spirits. Early in his premiership, he visited the trading floor of the New York stock market, where he rang the bell and gave a bullish pitch which ended “buy my Abenomics!”

It was a bold move, establishing that the performance of the Tokyo stock market would be a key measure of his success. No previous prime minister had elevated the stock market in such terms. Indeed, politicians in most countries are leery of commenting on stock markets precisely because their gyrations are so unpredictable. But Abe knew that if the Nikkei Index sank back into the doldrums, it would mean his project had failed.

He had to follow up and he did. A rolling series of reforms “encouraged” Japanese companies to pay much more attention to the interests of their shareholders. Likewise, Japanese financial institutions were nudged into taking their governance responsibilities much more seriously.

As a result, the relationship between investors and corporate managers has evolved out of all recognition. Hence, the increasingly common phenomenon of companies returning significant amounts of cash to shareholders via dividends and share buybacks, cited by Warren Buffett as one of the reasons he decided to invest.

Japan’s trading houses have changed too. They have always had top quality personnel, but for a long time they seemed to act as an arm of Japanese foreign policy, leading to debacles such as the half-built Bandar Imam Khomeini petrochemical complex which was destroyed in the Iran-Iraq war. In the 1990s, one venerable trading house failed to control a rogue trader and made huge losses in the copper market. Historically, several have exhibited bad timing in getting into and out of deals.

More recently, however, Japan’s trading houses have become more commercially minded and disciplined in their use of capital. They have also developed their own specialities, diversifying into downstream businesses such as retail, renewables, health care and IT.

Their willingness to co-operate with Buffett on joint projects would be a confirmation that they, and Japan, have changed dramatically. Put together the resources and capabilities of Japanese trading houses and the investment skill and foresight of Berkshire Hathaway and you would have a real dream team.