Published in Japan Forward June 27 2o24

In July 2024, a completely new set of Japanese banknotes will go into circulation. Like many countries, Japan refreshes the designs and the famous people featured on the obverse from time to time, but the person featured on the highest denomination note has only been replaced once since 1946.

That happened in 1984 when nineteenth educator and intellectual Yukichi Fukuzawa took over from the seventh century administrator and promotor of Buddhism, Prince Shotoku.

So familiar has Fukuzawa’s portrait become subsequently that “Yukichi” has sometimes been used as a slang term for the ten thousand yen banknote, like “Benjamins” in the United States. Now, though, Fukuzawa is about to give way to Eiichi Shibusawa, a serial entrepreneur who was born five years later and lived much longer.

The new note employs hologram technology

Banknotes are used less frequently these days, even in Japan’s cash-based retail economy. Yet even if they are replaced by digital money, there will surely be room for superior design and interesting choices of historical figures. Banknotes tell a story about the country that issues them. Through time, Japan’s highest denomination banknotes have depicted different versions of Japan itself.

So the switch from Fukuzawa to Shibusawa is intriguing and potentially significant. What kind of Japan will be ushered in by Eiichi Shibusawa?

Shibusawa’s main claim to fame is that he founded and invested in over five hundred companies, from banks and insurance companies to breweries and haberdashers, many of which are thriving today. If you take tea at the Imperial Hotel, you are patronizing one of Shibusawa’s start-ups.

Management guru Peter Drucker, writing in the 1970s, considered Shibusawa to be the greatest venture capitalist of modern times. Unlike the hard-nosed Yataro Iwasaki, the founder of the Mitsubishi Group, he had no interest in assembling a huge zaibatsu conglomerate, but would usually sell out of the companies he had sponsored when they could stand on their own two feet. A believer in ethical capitalism, rather like philanthropic businessmen such as Josiah Wedgewood and the Lever brothers, he sought “to maximise talent, not profits” as Drucker put it.

Shibusawa was a doer, rather than a thinker or writer, which is probably why he is less well known overseas than Fukuzawa. He was the first Japanese to drink coffee, which he took with milk and sugar, during his journey to France in 1867. While there, he became the first Japanese to invest in foreign securities, and his flutter in the Paris bourse turned a useful profit.

Back in Japan, he was recruited to the newly created Ministry of Finance as he was one of the few people who understood double entry accounting. After a year, he left and founded the appropriately named Daiichi Bank (“Number One Bank”) which today is part of Mizuho. The traditional slogan kanson minpei – “respect bureaucrats, despise the people” – was not for him.

Fukuzawa (1835-1901) and Shibusawa (1840-1931) knew each other and in some ways were similar. Both men had little standing in the feudal system into which they were born. Fukuzawa came from an impoverished samurai household, and Shibusawa from a peasant family that had done well by producing and trading indigo.

Both participated in official trips to Western countries in the years leading up to the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Both greatly valued education and founded famous universities – Keio in the case of Fukuzawa, and Hitotsubashi in the case of Shibusawa – as well as promoting women’s education.

Yet there are significant differences between them. Fukuzawa was not the enlightened proto-democrat that he has sometimes been painted as. According to historian Earl Kinmonth, Fukuzawa believed “the former samurai were still, in his opinion, the source of everything good and edifying in Japan. He declared that even when the shizoku (former samurai) went into unfamiliar occupations such as business or agriculture, they did better than merchants or peasants, thanks to their natural superiority”.

It is unclear whether Fukuzawa authored the anonymous essay “Datsu-A Ron” (“Goodbye Asia”) which recommended Japan to abandon Asian cultural norms in favour of the West. It was, however, in line with his thinking, as expressed in his prolific writings.

Indeed, Shibusawa initially had a poor impression of Fukuzawa who seemed an uncritical admirer of Western modernity. Specifically, the elder man considered the Analects of Confucius worthless, whereas Shibusawa always revered them, writing a book called “The Analects and the Abacus” late in life.

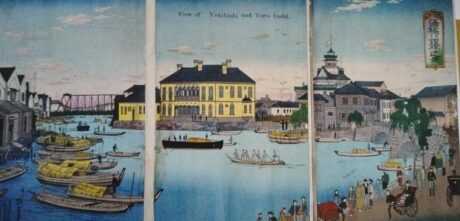

Print of Shibusawa’s residence in Nihonbashi

In 1984, when Fukuzawa took his place on Japan’s most prestigious banknote, it was still possible to describe the world in terms of the West and the Rest, with Japan as a honorary Westerner, thanks to its high level of economic development. The crisis-plagued “third world” was going nowhere on a GDP per head basis, and although a few small Asian countries were growing strongly, China had yet to recover from the ravages of Mao-ism, India seemed somnolent and the other large Asian countries were wracked with political and economic instability.

Much has changed since then. The “G7” world is now a shadow of its former self, with per capita growth flatlining in many Western countries and political fissures becoming ever more visible. Meanwhile, “the Rest” are doing much better, with China having reached a high level of technology and India, Indonesia and other countries sustaining rapid growth.

No surprise, then, that American strategist and think tanker Elbridge Colby is advocating a kind of geopolitical “Datsu-O”, or “Goodbye Europe”. His thinking is straightforward. America’s superpower status is dependent on its presence in this booming and increasingly wealthy part of the world. As the U.S. can no longer confront challenges in both Asia and Europe, it must choose the more important – which is clearly Asia.

SHIBUSAWA & DAIKOKUTEN

Most countries use their banknotes as signifiers of the culture and values they hold – or aspire to hold. American banknotes, bearing the images of long-dead presidents and imposing buildings in Washington, tell a story about America’s brand of democracy.

English banknotes bear the image of the sovereign on the obverse side, and the reverse side features famous writers, inventors and national heroes such as Jane Austen, Adam Smith and the Duke of Wellington.

Euro banknotes, by contrast, bear no human images, presumably because that might privilege one of the pre-existing nation states. Instead, fittingly, they depict a series of bridges which cannot be found anywhere because they are imaginary. Perhaps one of the signs of the success of the EU project will be when those non-existent bridges are replaced by Dante, Archimedes and Mozart.

The story told by Chinese renminbi banknotes is a lot clearer and more disturbing. Since 1999, all denominations have depicted the figure of Mao Zedong, the author of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. At least, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has not decorated its banknotes with pictures of a young, handsome Josef Stalin.

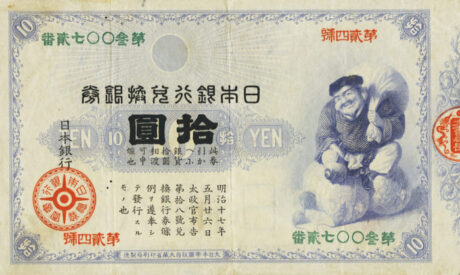

Japan’s monetary history is well displayed in the Bank of Japan’s Currency Museum in Nihonbashi. The first banknote of the modern era is one of the most remarkable. In contrast to the austere administrators and intellectuals that were to follow, it features a plump, merry, short-legged fellow called Daikokuten.

Japan’s first banknote

One of the Seven Gods of Good Luck, Daikokuten was particularly associated with prosperity, fertility, sexuality, farmers and bankers. He came to Japan by way of India and China.

In the immediate post-war period, Prince Shotoku was the ideal front man for Japan’s most valuable banknote. Under militarism, Buddhism had been downgraded in favour of State Shinto, and in some cases devotees had been harshly treated. The Prince evokes the long history of Buddhism in Japan, pacifism and good relations with China.

Likewise, Fukuzawa was the man to symbolize the Japan of the 1980s that had Westernized so successfully that its auto and consumer electronics companies had outcompeted its rivals.

Shibusawa is very different. Indeed, he embodies several of the associations of the mythical Daikokuten. Born into a farming family, he set up multiple financial companies, including banks. In terms of the companies he fathered, he was highly fertile – and he also produced thirty eight children of his own. Most of all, he stands for shared wealth. Not for nothing has he been dubbed “the father of Japanese capitalism”.

His appearance on the ten thousand note promises a different Japan, more entrepreneurial and cosmopolitan, both Asian and Western at the same time. It should be a fascinating era.

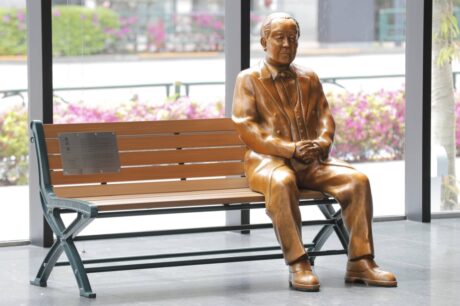

Statue of Shibusawa at the Tokyo Stock Exchange – which he helped to found