Published in Nikkei Asia 14/11/2024

There could hardly be a greater contrast in investment philosophy and personal style than that of Masayoshi Son, CEO of the SoftBank Group, and Warren Buffett, the Sage of Omaha. Yet, as author Lionel Barber reveals, the two men did meet in 2017 when Masa, as he is familiarly known, flew directly from Tokyo to Buffett’s home ground in an attempt to interest him in SoftBank’s new $100 billion Vision Fund.

This was a Godzilla-sized venture capital vehicle, featuring several companies on eye-popping valuations. The most notorious was “WeWork”, which called itself ‘a provider of co-working spaces’. In reality, it was an office rental business hyped to the skies by its long-haired, egomaniacal founder, Adam Neumann, abetted by Masa’s insistence that he set his sights higher and higher.

Nice T-shirt, Adam

Barber quotes an unnamed SoftBank insider as claiming that giving Neumann such an enormous amount of funding was equivalent to “feeding a monkey alcohol” – and so it proved.

At the peak of the delirium in 2019, SoftBank put another $2 billion into “WeWork”, giving the company the astonishing valuation of $47 billion dollars. Four years later, having endured all kinds of disasters and scandals, it finally gained a stock market listing at a valuation of one percent of its former glory.

Even that was too much. This summer it filed for bankruptcy. The ‘monkey’ did rather better than his investors, being royally paid to go away. Currently, Adam Neumann has a net worth of $2.2 billion, according to Forbes.

Unsurprisingly, Buffett politely declined the opportunity to invest in the Vision Fund. His reputation as the greatest investor of modern times has been built on patient accumulation of undervalued stocks. He eschews leverage, which he compares to an addictive drug.

For decades, he stayed away from technology stocks on the grounds that their future was too unpredictable – though he has recently built a large position in Apple, which he reckons has created an eco-system that will last. An extraordinary man pretending to be ordinary, he is known to eat breakfast at McDonald’s and swill down Coca Cola all day.

Masa is the antithesis of Buffett on all these fronts. Leverage is his lifeblood. In times of crisis, it has taken him to the brink but it has also allowed him to create outsize returns. He invests only in tech companies because he believes he has a superior understanding of future developments.

Often, he seems to act by instinct. Personally, he takes great pains to guard his privacy, though Barber tells us that he has a “starter castle” in California and a huge house in Kansas he has visited just once, for a night, as well as his amazing pad in central Tokyo, with its indoor electric golf course capable of mimicking several of the world’s great courses.

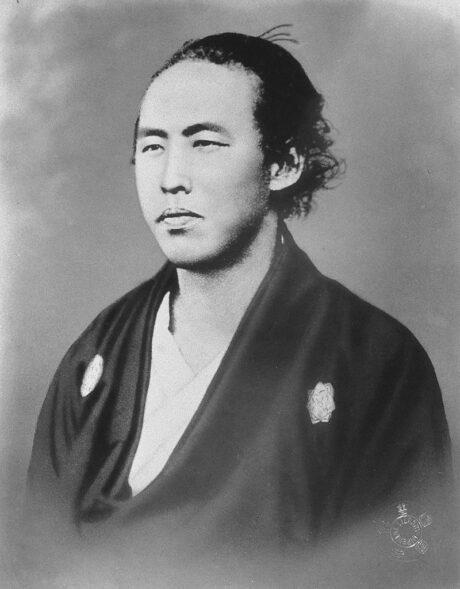

He is an extraordinary man who doesn’t hide his extraordinariness. On the contrary, he likens himself to such figures as Napoleon and Ryoma Sakamoto, the brilliant low-born samurai who mapped a path forward for modern Japan. His favourite beverage is Domaine de la Romanée Conty wine at about $10,000 a bottle for his preferred vintage.

Masa with Indian PM Modi

With “Gambling Man: The Wild Ride of Japan’s Masayoshi Son”, Lionel Barber, the former editor-in-chief of the Financial Times, has produced a definitive and highly entertaining biography of this fascinating figure, who seems to be everywhere yet is strangely elusive.

The author seems to have interviewed every important person in Masa’s life, from his father to the American professor who went “red with anger” when he recalled his dealings with young Masa in 1978. Barber’s book also tells us a lot about the world we live in, how the intersection of technology and finance has created enormous fortunes and changed lifestyles everywhere.

Masa is a natural born entrepreneur but of a very different kind to post-war giants like Soichiro Honda of Honda, Akio Morita of Sony and Kazuo Inamori of Kyocera. Although he runs a complicated conglomerate which includes large-scale wireless networks in both Japan and the U.S., in some ways he resembles a super-aggressive hedge fund manager.

Barber talks of his “unshakeable self-belief.” Indian telecom billionaire Sunal Mittal, who sat on the SoftBank board until he had enough of Masa’s wilful ways, declared that “the man has balls of steel.”

Where did that determination come from? Perhaps two near-death experiences had something to do with it. In 1982, at the age of 24, Masa contracted chronic hepatitis and was in and out of bed for two years before an experimental treatment cured him.

The second scare was of a financial nature. The “Dot Com” stock market collapse of 2000-2003 wiped out 98% of his wealth. Many others licked their wounds and walked away, chastened. Masa doubled down, convinced that technological change would deliver great wealth to those who had faith in it.

His story starts in Japan, but he has made himself a global figure in a way that even Akio Morita never did. Barber describes interactions with Steve Jobs, Donald Trump, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, casino tycoon Sheldon Adelson and Elon Musk.

SoftBank is a Japanese company but many of his senior executives and advisors are – extremely well paid – foreigners. He has poured venture capital funds into promising Chinese, Indian, and of course American companies but not yet, it seems, any Japanese ones.

With Steve Jobs

Masayoshi Son was born into an ethnic Korean family that had been living in Japan since the early years of the twentieth century. The family started off poor but became wealthy in the 1960s thanks to pachinko, a slot machine game that gives bored housewives and frazzled salarymen a chance to win modest prizes. Masa’s father was the pachinko kingpin of Kyushu, Japan’s third largest island, and drove a Mercedes.

Many ethnic Koreans have officially taken Japanese names. As Barber notes, Masa waited until the rules were relaxed in the 1980s and it was possible to become a Japanese citizen without adopting a standard Japanese family name. His use of the surname ‘Son’ marks him out as an ethnic Korean but his personal name is as Japanese as you can get. He‘s a one off, almost certainly the only ‘Masayoshi Son’ on the planet.

It was obvious that the pachinko halls of northern Kyushu were never going to be a big enough stage for the ambitious youngster, and he persuaded his family to let him finish his education in California. There, in the late 1970s, he came across the nascent world of personal computers and what was to become “tech”. That was the big idea he had been searching for, and it would be the lodestone of his entire career. Expressing what kind of person he wanted to be, he drove a Porsche.

The young Masa

Back in Japan, he founded SoftBank in 1981. As is often the case with successful entrepreneurs, early partners tell stories of dodgy dealing and broken promises. But though he was clearly a one man band, he was supported by some senior Japanese who recognised his charisma and drive.

If Masa is a gambling man, he is a very skilled and selective one. In the late 1980s, Japan went through a maniacal real estate bubble which led to the grounds of the Imperial Palace having a theoretical valuation greater than the entire state of California. It was said there were one hundred million real estate speculators (Japan’s adult population, roughly) in the country.

Masa, who had no interest in sectors other than technology, was not one of them. Unfortunately, his father, a much less discriminating gambler, racked up a huge amount of debt on bad land deals and had to be bailed out by Masa.

SoftBank became a listed company in 1994, its main assets being Masa’s ingrained techno-optimism and fireproof confidence. One year later, he made the first of his four transformational acquisitions, inserting himself into the Dot Com world at an early stage by taking a 40% stake in Yahoo.

Showing that he needed no lessons from Donald Trump on the art of the deal, he acted both ‘good cop’ and ‘bad cop’, telling the two founders how much he liked their business but also that he would sink them by financing their number one rival if they refused his proposal.

Early days of SoftBank

It worked. By the end of the century, SoftBank had become the dominant force on the Japanese internet, largely owing to the popularity of wholly-owned subsidiary Yahoo Japan. Masa’s ambitions already stretched well beyond Japan and even beyond America, as he showed with his second bold acquisition, which turned out to be the moonshot of a lifetime.

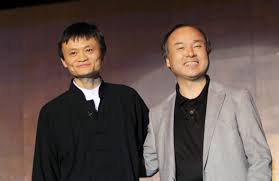

At a venture capital “speed-dating” event in Beijing in 1999, he overrode the objections of his colleagues and indicated that that he would invest in the sketchy plans of a diminutive Chinese man who had previously been an English language teacher.

Masa already knew that the internet favoured winner-takes-all economics, and with China growing at double digit rates, successful online businesses could scale up to unimaginable size. And at this stage, he could buy a significant stake for what amounted to chump change.

But why did he ignore the more polished presenters and plump for Jack Ma and Alibaba? Lionel Barber’s answer: it was “the animal smell of a fellow underdog.” Despite the vagaries of Chinese politics, SoftBank’s 30% stake in Alibaba has been an enormous winner. The company’s current market capitalisation stands at a gigantic $230 billion. SoftBank has sold most of its investment but remains the largest holder.

With Jack Ma

Masa’s third crucial deal was highly strategic, turning him from a talented improviser to a businessman whose product was used by millions of Japanese citizens everyday. By purchasing Vodaphone’s Japanese telecom business, he accomplished a number of goals. He now had regular cashflow, not just illiquid stakes in other people’ s enterprises. By entering the world of telecommunications, he had gate-crashed the inner sanctum of Japan Inc. where matters of national security were involved. No longer could he be considered a marginal figure.

Better still, the other two telco operators had been government agencies until the mid-1980s. NTT, in particular, was highly bureaucratic and uncommercial, as it proved by refusing to accept Apple’s terms for the i-phone, thereby giving SoftBank an open goal. Masa could not compete on technology or capital but he was far ahead on business acumen.

The last – so far – of Masa’s transformational acquisitions is the full purchase of the British chip design firm ARM in 2016 for the sum of $31 billion. At the time, many believed he had overpaid but subsequently the company’s skillset has been deemed important to the field of generative AI.

The new target

As a result, ARM’s market capitalisation has quintupled. To put that into perspective, Masa has made two and a half times as much money from ARM as he lost from the disaster of WeWork. Not bad odds for a gambling man.

Masa’s ability to bounce back from setbacks, usually of his own making, is awe-inspiring. But it should be noted that his two heroes came to sticky ends, Ryoma being brutally assassinated on the eve of the Meiji Restoration and Napoleon meeting his Waterloo, after which he was stuck on a tiny island for the rest of his days.

The great Ryoma Sakamoto

Masayoshi Son’s “wild ride” is far from over. AI may fail to deliver the high value products that are required to justify the vast investments that are being rolled out. Or there might be another financial crisis that crushes highly leveraged players like Masa. Or he may simply go from strength to strength, being recognized as the world’s greatest venture capitalist, just as Warren Buffett is recognized as the world’s greatest investor.

What ever happens, it promises not to be boring. Lionel Barber’s thoroughly researched biography will likely need many more pages in future editions