I’m sitting in a dingy jazz club in Shimo Kitazawa. A young alto sax player is performing a ninety minute solo improvisation which involves moving around the room, testing the sonorities of walls, glasses, piano-strings.

A plastic bottle of hand disinfectant sits on the counter, but none of the half-a-dozen listeners is wearing a mask. Neither is the club’s ‘master.’ Neither, of course, is the alto player.

Neither am I, for that matter. A mask would impede the free flow of sake from cup to stomach. But I do have one in my pocket, reasonably clean and ready for use.

Most experts say ordinary masks, intended for hay-fever sufferers, have little efficacy against the virus. In any case, the shape of my nose creates vents on either side of it, which means I inhale a good amount of unfiltered air.

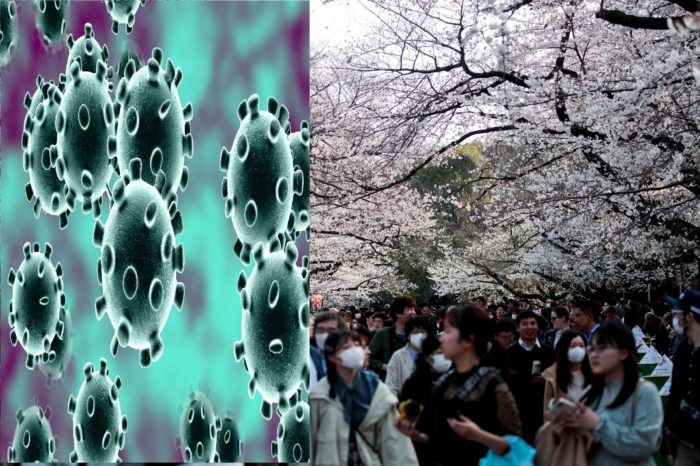

The mask has become a social signifier. It shows you are part of the team, that you accept the need for solidarity. Foreigners visiting Japan used to think that mask-wearing was a strange, even comical Japanese custom. They’re not laughing now. People all over the world are masking up. If they can, that is. It turns out that China accounts for 99% of mask production and puts its own needs first.

Here in the jazz club, though, there is another dynamic at work, which is “the show must go on.” The jazz economy is intensely fragile. If the customers don’t appear, the clubs will quickly go bust and the musicians will have no income.

The same goes for many other businesses and sectors, of course, in Japan and elsewhere. A prolonged enforced halt to economic activity will have a devastating human and social cost.

So as the alto player wanders back and forth, no doubt projecting tiny droplets of saliva into the air, we keep our masks in our pockets. We’re on his side – for the moment, at least.

Walking back through Setagaya, I come across small knots of local people enjoying yozakura, cherry blossom viewing by night. They sit around trestle tables, chatting, drinking beer, nibbling yakitori. No tourists, no karaoke singing, no stressed-out cops yelling through bull-horns.

This could be the best cherry-blossom viewing in years.

***

I’ve a feeling I may have been infected with the coronavirus already. Back in Britain in late December and early January, my elder daughter and younger son suffered from a flu-like illness characterized by a fever and a dry cough. My wife had a long-lasting cough too. I had neither, but felt lousy for ten days. Could that have been it?

At the time, nobody in the UK was talking about the virus. Everybody was talking about Brexit. Nobody talks about Brexit any more. The only news, the world over, is coronavirus news.

***

The peppermints had disappeared from pharmacies because a lot of people sucked them as a defence against infection.

From The Plague, by Albert Camus

***

One of the first casualties of this pandemic is John Stuart Mill. The British philosopher, considered to be the founding father of classic liberalism, developed the harm principle: individuals’ actions should only be limited when harm is caused to other individuals. That has been left far behind. Fear of infection, like fear of invasion, drives a more fundamental, tribal morality.

In a few short weeks, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government has suspended freedom of assembly and movement and confined citizens to their homes, with stark warnings about unauthorised gatherings.

Busybodies are snapping at young adults for not observing the prescribed two yards of social distancing, and the police are overwhelmed with citizens snitching on each other. Hoarding is blasted as a villainously anti-social crime, yet almost everyone does it.

According to a YouGov survey, 63% of the UK public want food rationing, and 58% want to stop all travel to the UK.

To ram home the wartime parallels, Vera Lynn, the “forces’ sweetheart” of the early 1940s, has been wheeled out at the grand old age of 103. Her record company has created a new video, now available on YouTube.

Supra-national organizations like the EU and the World Health Organization have declared that travel restrictions between countries will have no effect in slowing the spread of the virus. Nobody is listening. Travel restrictions are in place all around the world, even in the countries that make up the EU’s Schengen area, which is supposed to be border-free.

In times of peril, the nation-state is all you’ve got. In most cases, its leaders – such as Johnson, President Trump, Prime Minister Abe and President Macron – are experiencing sharp rises in their popularity.

***

The cherry trees lining the Meguro River are of the Somei-Yoshino variety, the most common in Japan and widely celebrated for its pale, five-petalled flower.

All Somei-Yoshino cherry trees in Japan, and indeed elsewhere in the world, are descended from the same ancestor which was created by splicing in early eighteenth century Edo (now Tokyo).

Small green leaves appear only after the flowers have fallen.

***

The world around us

Has become nothing other

Than cherry blossoms

Ryokan

***

While supposedly individualistic and sceptical Westerners give up their civil liberties without a murmur, the “conformist” Japanese have been hesitant about relinquishing their usual enjoyments.

The day after Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike called for people to work from home was a fine one. A steady stream of people came to enjoy the cherry blossoms along the Meguro River. The numbers were less than ten percent of what they are in a normal year, but people seemed relaxed as they strolled across the bridges.

Kimono-clad young ladies take selfies; a chap in a flat cap walks three enormous Afghan hounds; middle-aged shutter-bugs armed with tripods and zoom lenses get right up close to the profusion of blossoms.

Signs remind us that this is by no means an ordinary year.

“Let’s stick to the coughing etiquette.”

“Please be restrained in your blossom-viewing”

“Street-stalls are forbidden.”

In reality, there are plenty of street-stalls selling sweet potatoes, hotdogs, fried chicken, beef skewers, salted tongue, sweet sake and limited edition cherry blossom beer. There are even some Turkish gentlemen offering mystery meat kebabs.

Later in the evening, a twenty piece big band plays in an Akasaka jazz club. The musicians are more numerous than the audience, but play their hearts out as if on stage at the Newport Jazz Festival.

***

My friend Kenta believes that WHO is in the pocket of the Chinese government, hence its tardiness in issuing the declaration of a pandemic, hence its refusal to discuss Taiwan’s success in combatting the disease.

I don’t know about that, but WHO did seem to let political correctness get in the way of speedy and effective virus control. Its press releases in February warned people about using “stigmatizing language” such as “suspect case”, “transmitting COVID19” and ”infecting others.”

It went on to recommend the use of social influencers to engage in such gestures as “shaking hands with a leader of the Chinese community.”

What if the Chinese authorities had shared information with foreign governments as soon as they realized how serious the outbreak was? What if WHO had issued an early clarion call, recommending tight travel restrictions with China, just as China did itself with Wuhan? Perhaps the spread could have been delayed and slowed down. Perhaps Italy’s agony could have been avoided.

***

Today it snowed. It’s the first time I’ve seen snowflakes falling amongst cherry trees in full bloom. Apparently, there is a haiku season word for this phenomenon, used only in certain regions of north Japan. It is sakura kakushi, which means “concealing the cherry blossom.”

Unseasonable snow was falling on the cherry blossoms in la1e March 1860 when Ii Naosuke, the Shogun’s chief minister, was hacked to death by samurai of the Mito clan. That direct challenge to the ruler’s authority ushered in a period of turmoil that culminated in the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

An omen?

A detail from Yoshitoshi’s “Blossoms Falling in the Snow”, depicting the assassination of Ii Naosuke.

***

There is much conjecture about the Japanese experience of the coronavirus crisis. At time of writing, the number of related deaths is around 54, or 0.4 per million of population. This is a low number, far less that the 3.0 of South Korea, which has been highly praised in some quarters for its success in combatting the disease.

On the face of it, Japan should be a prime candidate for a disastrous outcome. It has the oldest population in the world by far, and aged people are extremely vulnerable to the virus. It has huge numbers of Chinese tourists and was late in putting any entry restrictions in place. People journey to work in jam-packed commuter trains. Compared with many other countries, it has done little testing and there has been no lockdown yet.

Some critics believe the surge has yet to come. Others claim that there has been some trickery with the numbers. Yet the virus has been at large in Japan for at least eight weeks already, and if there were a Lombardy-style catastrophe happening, it would be impossible to hide.

Perhaps Japanese social customs have been a factor. Many enforce hygiene and social distancing – bowing instead of shaking hands, taking off your shoes before entering a home, washing before entering a bath, etc. People are habituated to wearing masks from an early age – pre-teen schoolkids use them when serving lunch to their schoolmates.

It is also the case that elderly Japanese rarely suffer from obesity, hypertension and heart problems, conditions which are often co-morbidity factors for coronavirus in the West.

No doubt such questions will occupy researchers for years to come. In the meantime, Japanese people may well remain rationally blasé about the risks, eating and drinking in their favourite spots, listening to their favourite music, enjoying what remains of the cherry blossom season.

On the other hand, a surge in fatalities could change everything.

***

Scattering blossoms

Blossoms left also become

Scattering blossoms

Ryokan