Published in Nikkei Asia February 27 2025

It is hard to imagine the brilliant novelist Yukio Mishima taking a driving test, but he did in 1962, eight years before his sensational ritual suicide.

At the somewhat mature age of 37, Japan’s greatest “sacred monster” showed up at a smelly out-of-town test center and, along with 200 other applicants, answered a series of pernickety multiple choice questions about road safety.

We know this because he crafted an amusing short story about the episode, with himself as a nihilistic dandy who sets his sights on a much younger lady driver – and pays the price.

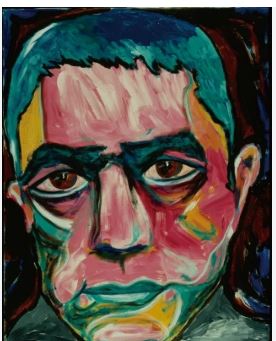

David Bowie’s painting of Mishima – 1975

“Cars” is one of the stories, translated into English for the first time, that make up this collection of pieces written in the last decade of Mishima’s life. The publication by Penguin U.K. of “Voices of the Fallen Heroes and Other Stories” also marks the 100th anniversary of his birth on Jan. 14, 1925.

Even for readers familiar with Mishima’s acclaimed novels, what stands out immediately in the short stories is the prodigious range of the author’s talent. Among the tales we find a surrealist ghost story set in Dickensian London; a factual account of a midnight break-in by a demented fan (“he came from inside me”); and the pathos of a father-fixated teenage girl confronting reality. Most of them dwell on Mishima’s favorite themes of beauty, death and sex.

The painstaking level of detail helps to make his fictional world so convincing. In “Cars”, the characters discuss Colin Chapman’s design for the Lotus Elite and praise the MGA 1600 MK1, the latest model from British auto maker MG.

In “Moon”, the young delinquents listen to “Yaya Twist” by Richard Anthony, an obscure French singer who did covers of R&B hits. Set in an abandoned church, the story, which is full of religious symbolism, features a teenager nicknamed Hymino. Hyminal was the term for the recreational drug methaqualone, known in the West as “’ludes” or “mandies”.

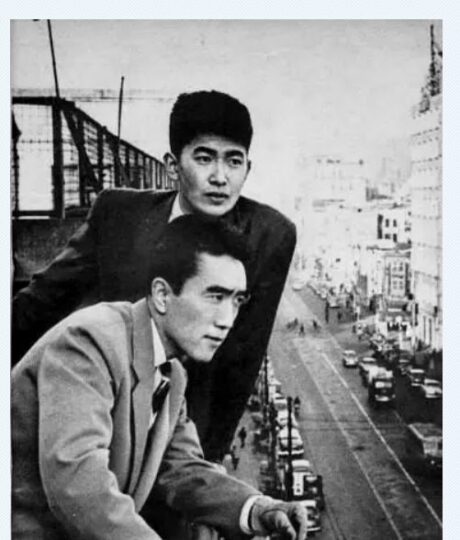

The drug, not illegal at the time, was used by Mishima and his young friend Shintaro Ishihara, later to become a three-term Governor of Tokyo.

Mishima with fellow novelist Ishihara

Despite the non-stop whirl of activity which Mishima threw himself into – acting in gangster and samurai films, travelling in Europe and America, debating violent radical students, hanging out at discos, and setting up his private army (likened by some to a troop of Boy Scouts) – there was no diminution in the quantity and quality of his output.

“The Flower Hat” is one of the most extraordinary – and shortest – of the pieces. It has a Mishima-esque narrator sunning himself in San Francisco’s Union Square after buying some snazzy clothes. Suddenly, amid the prosperity and ease, he experiences a terrifying vision of the end of the world.

This was written well before the Cuban Missile Crisis but Mishima somehow intuited the fragility of what we call everyday life. It is a token of his enduring appeal as a writer that the story was carried in full in Britain’s Daily Telegraph earlier this year and described as “a masterpiece” in The Spectator.

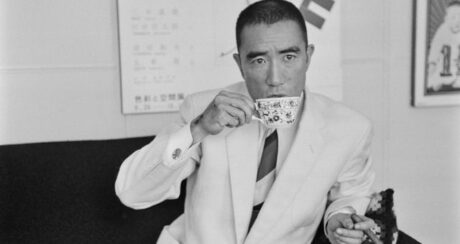

Mishima takes tea

The title story, “Voices of the Fallen Heroes,” is the piece de resistance. By far the longest story, it is influenced by traditional Noh theater, which Mishima knew well, having written a number of well-received modern-day versions of the genre.

It is also likely to be the most controversial, especially if taken with Mishima’s exaggerated reputation as a bellicose militarist. If read carefully, though, it comes across as a remarkably subtle piece of work which criticizes Emperor Hirohito directly and carries a possibly semi-conscious anti-war message.

The spooky set-up takes place on a stormy night with rain slashing down and trees groaning and writhing. The narrator has been invited to take part in a kind of séance at a Shinto shrine but has no idea what to expect. The head priest plays a stone flute, and a young, blind acolyte acts as the medium. The first batch of spirits arrives, filled with anger and sarcasm at being betrayed.

They are the young officers who mounted a coup d’etat in 1936, so distressed were they by the dire conditions in the impoverished villages where their families starved and their sisters were sold into prostitution. The Emperor and his coterie of advisors rejected this dangerously populist and progressive movement, and the coup participants were tried for treason.

Not even allowed the honorable death of ritual suicide, they were “fastened to crosses” – the Christian reference is deliberate – on a parade ground and shot, leaving the way clear for General Tojo and the military top brass to rule and ruin Japan.

The emperor – supposedly “rich in compassion” and a “loving mother” to the inexperienced troops – had condemned them with his own words.

The spirits declaim their fate. “At this point the Imperial forces commanded by His Majesty, our Generalissimo, ceased to exist, and the grand righteousness of our imperial land collapsed. On the day when pure-hearted warriors became ‘traitors,’ the dominant military faction, quasi-Nazis filled with malice, opened up the road to war with no obstacles of any kind.”

The smell of the ocean tide ushers in another group of betrayed spirits. Handsome and younger, these are Kamikaze pilots who died in the last year of the war. Clearly aware that the cause was hopeless, they were willing to die because they believed they would be mystically united with their divine Emperor.

“Only a god could complete and perfect our genuine tragedy – this irrational death, this solemn slaughtering of our youth. Were this not so our deaths would become nothing more than a foolish sacrifice… Ours would be the death not of a god but of a slave.”

Yet the Emperor, answering “a suggestion” from the victorious American occupiers, declared himself an ordinary human – just months after he had been praising the Kamikaze pilots for turning themselves into balls of flame.

Now the howling storm reaches its climax. The voices become increasingly agitated, and the medium can communicate only scraps of their words. “Ah, how lamentable! How outrageous… When His Majesty declared that he was only human, the spirits that died for the sake of a god were stripped of their honorable name… they know no peace… no matter how much force was used… no matter how great the threat of death… His Majesty should not have said that he was no more than human… never stating that it was a ‘false’ conception or a lie… even though in his heart he might have thought it so …” The story ends with a shocking but highly appropriate coda.

In reality, could the Emperor have got away with the “noble lie,” as proposed by that last spirit? It is unlikely. Whether deliberately or not, Mishima the right-wing firebrand has written a story that pulls the rug from under Japan’s Imperial Institution.

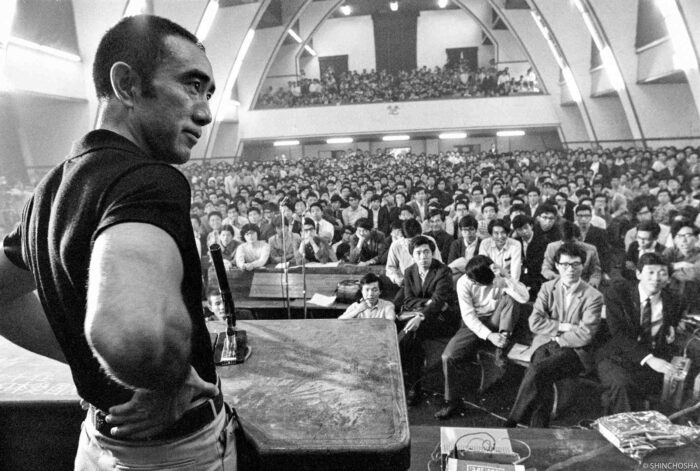

Mishima in New York

Mishima was a complex and contradictory figure, and the spectacular act of performance art with which he ended his life has inevitability colored his posthumous reputation.

Interestingly, Philip Shabecoff of the New York Times, who interviewed him in early 1970, had this to say after his death. “Although his private army — the Tate no Kai (or Shield Society) — led many Westerners to believe that he sought to revive Japanese militarism, he actually loathed the militarism represented by the Japanese Army of pre-World War II years. He regarded that militarism as a foreign import alien to the Japanese spirit. What he was really seeking was a return to the samurai tradition.”

Mishima also told the journalist, half-seriously, that he worked so hard at bodybuilding because he did not want to live beyond 50 and hoped to leave a good-looking corpse.

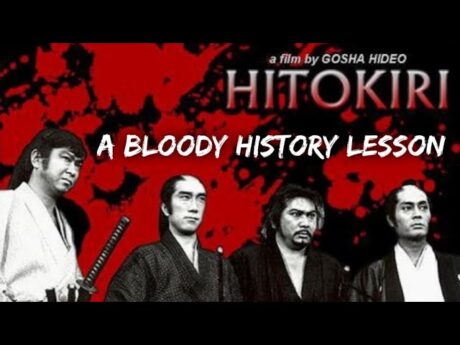

In 1969 Mishima took a leading part in the in the star-studded samurai movie Hitokiri. Mishima is second from the left.

In recent years, many more of Mishima’s works have been translated into English, including several of the “entertainments” that he wrote quickly for money. Lighter novels like “Life for Sale” and the science fiction-themed “Beautiful Star” (Mishima was a member of the Japan UFO Society) are funny and affecting and give a different perspective on the man and his works.

That is congruent with the recollection of Paul McCarthy, an American translator and writer who translated the title story and two others in this collection. He knew Mishima and found him to be modest, kind and witty.

According to John Nathan, translator and scholar, who wrote the introduction to the book, Mishima wrote 170 short stories altogether. As only 20 have been translated so far, it is more than likely that there are plenty more surprises in store for English language readers.

Voices of the Fallen Heroes and Other Stories