Published in Nikkei Asia on April 24 2025

This April marks Shuji Terayama’s ninetieth birthday. He is not around to celebrate it, having succumbed to chronic nephritis in April 1983, but it is interesting to speculate what he would have got up to if he had lived.

For those who are unfamiliar with the name, Terayama was a huge figure in the Japanese counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. Originally a poet specialising in the thousand year old tanka form, he was the founder, producer and main playwright of an outrageous avant garde theatre troupe called Tenjo Sajiki, also a maker of disturbing experimental films, a novelist, a horse racing columnist, a songwriter, a boxing fan and one of the few Japanese intellectuals to “get” the Beatles when they played the Budokan in 1966.

Throw Away Your Books

Adventurous young people followed his activities avidly, and many hung around hoping to join his troupe, some succeeding. Such slogans as “run away from home” and “throw away your books and run into the streets” gave him the reputation of a countercultural Pied Piper.

These reflections come to mind after watching “Japanese Avant Garde Pioneers”, an inspiring new documentary created by French director Amelie Ravalec. In its hundred minutes of running time, the film provides the viewer with a portal into a phantasmagorical world that is grotesque, full-on erotic, dangerous and as absurd as “Alice Through The Looking Glass” – yet comical, exciting and unforgettable.

And where is this place to be found? In Japan, of course – but in kind of an alternate reality that turns on its head every cliché you have heard about the country and its inhabitants.

From “Laura”

Ravalec, who has delved into other sub-cultures, was able to get access to important participants such as innovative photographer Daido Moriyama, famed for his “grainy, blurry, out-of-focus” style, and contemporary artist Tadanori Yokoo, whose psychedelic theatre posters prepared audiences for the wild and crazy happenings they were about to experience.

She also makes good use of archival footage of Terayama and other leading lights of the era in their prime. Rightfully, the emphasis is on the visuals, which are extraordinary. No more time than is necessary is given to non-Japanese talking heads, of which I must reveal I am one.

Inevitably, many major figures are no longer with us. Eikoh Hosoe who befriended Yukio Mishima and photographed him in a series called “Killed By Roses”, passed away in September. Graphic artist Keiichi Tanaami died last summer, on the eve of his magnificent retrospective at the National Art Center in Roppongi.

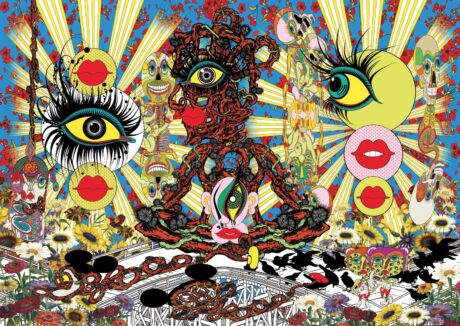

Tanaami’s world

Of course, there are some active survivors who seem ageless. In 1969,Carmen Maki scored a million selling hit song with the Terayama-penned “Toki ni wa Haha no Nai Ko no Yō ni” (“Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child”, not the same as the black spiritual with a similar title.) From folk singer she morphed to Janis Joplin-style blues belter, then rock diva, and, more recently, interpreter of art songs and spoken word pieces by Terayama and others.

Likewise, the raggle-taggle free jazz orchestra called Shibusa Shirazu (“Never Be Cool”), continues to shake the rafters of the Pit Inn jazz club once a month with its retinue of Butoh dancers and glamourous female performance artists. It tours overseas frequently, and has played the UK’s Glastonbury Festival four times in a row.

My Dear Lady Jane

More typical these days is the demise of “Lady Jane”. Named after the Rolling Stones song, it is a bar, meeting place and music venue in the Shimo Kitazawa district, not far from Shibuya. The owner, Yutaka Oki, was involved in the “angura” underground theatre movement before opening for business in 1975. Early customers included Ryuichi Sakamoto of Yellow Magic Orchestra fame, and theatre director and playwright Hideki Noda. More recently, Nobuyoshi Araki, notorious for his risqué bondage photographs, had his studio nearby and sometimes dropped in.

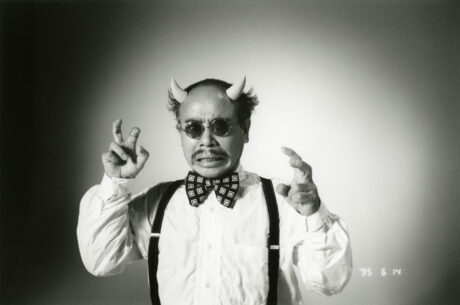

The devilish “Araki”

Now after half a century, Lady Jane is closing its doors. The reason? Shimo Kitazawa has changed drastically in the last fifteen years. No longer the natural abode of impoverished artists and musicians, it has been redeveloped and gentrified by the giant railway companies and their real estate arms.

Shinjuku’s Golden Gai, another remnant of Japan’s counterculture, is facing a different, some would say worse, fate. The warren of tiny bars where writers, editors, film people, theatre people and figures from the demi-monde would bar-hop until dawn has become a global tourist attraction. Spurred on by tiktok influencers, hordes of “inbound” travellers surge through the narrow lanes in pursuit of the perfect selfie for their Instagram feeds. No Japanese customers are anywhere to be seen.

The Japanese avant garde was created in a specific, non-repeatable set of circumstances. Most of the major protagonists were born before or during the war and witnessed the 180 degree shift in values as enemies became allies overnight, and what had been deemed meritorious conduct was laughed at or censured. In the arts, as well as elsewhere, authority and officially sanctioned tradition no longer counted for anything. Instead, a vast empty space opened up, waiting to be filled.

Freak Shows

One creative possibility was the search for native Japanese traditions that had been considered improper or backward during Japan’s pre-war modernisation drive – such as Terayama’s love of freak shows, and Hosoe’s photo project about a supernatural flying weasel that haunts rice fields in north Japan. Coupled with the menacing figure of Butoh pioneer Tatsumi Hijikata, it offered a nightmarish vision of rural life.

Mishima & Hosoe – Ordeal by Roses

For some the trauma of Japan’s lost war was itself a theme that would last a lifetime. Graphic artist Tanaami was four years old when the B-29s appeared over Tokyo with their loads of incendiary bombs. After some nights in the shelters, his mother decided to take him to a distant location on the Japan Sea coast. “Have a good look around you,” she said as they boarded the train in the posh Meguro district. He did as instructed, and when he returned to Tokyo after the surrender a few months later, the entire district had been reduced to ash and red dirt.

Tanaami passed away at 88. In Ravalec’s film, he states “my life has been very long and I have had a lot of experiences but nothing can top the experiences I had during the war. It is the hardest memory I have, and it deeply impacted me mentally and physically.”

You can see that from his work, which is packed with images of Elvis, American nudes and the Boeing B29 Superfortress bomber, as well as Buddhist iconography.

Terayama’s take on war memory was typically off-beat. As a ten year old, he had to flee his burning home in north Japan during the last stages of the war. His father, originally a policeman, was drafted into the army and never returned from the war. In his surreal autobiographical film, “Pastoral: To Die in the Country” the young Terayama character goes to Terror Mountain (“Osorezan”). There he attempts to communicate with his dead father via a blind medium, hoping to stop his mother’s nagging. It doesn’t work. Later in life, Terayama would sometimes claim that his father had been executed as a war criminal, which was a fabrication, but the Pied Piper of the underground preferred what was interesting to what was factually correct.

Young Terayama talks with his middle-aged self

For better or for worse, the world moves on. The trauma of the lost war has little resonance for today’s Japanese, who seem much more comfortable in their own skin than previous generations. As a consequence, the power, creativity and daring of the post-war avant garde is unlikely to be repeated. All the more reason, then, to celebrate what the pioneers achieved, as Amelie Ravalec does in her illuminating film.

Starting this April, there will be more than 100 screenings over the next six months, taking place all over the world, from Memphis Tennessee to Hong Kong, from Helsinki to New South Wales. The film will come to Japan in 2026. The busy schedule is a testament to Ravalec’s dedication and also the level of interest in the Pioneers’ work.

As for a 90-year old Terayama, it’s hard to believe that such a restless spirit would have carried on with the underground theatre performances as if the 1970s had never ended, as his recently deceased rival Juro Kara did. More likely, he would have followed up the cinematic brilliance of feature films like “Pastoral: To Die in the Country” and “Farewell to the Ark” with a series of Fellini-esque big budget movies, and then reinvented himself several times over, creating new forms of provocation.