The film version of Ah, the Wasteland, Shuji Terayama’s only novel, has just been released in Japan. The two boxers who are the joint protagonists of the story are played by Masaki Suda, a high-profile young actor with a large female following, and South Korean actor-director-screenwriter Yang Ik-june, best known for the ultra-violent Breathless (2009).

The director is Yoshiyuki Kishi, whose debut, the stalker film A Double Life, appeared last year.

The cinema release of Ah, the Wasteland comes in two stages, with the second half due to appear on October 21st. The film will also be available on streaming services and on DVD / Blu-ray. To mark the occasion, one of the bars in the legendary Golden Gai entertainment district has been temporarily refitted and renamed as Bar, the Wasteland.

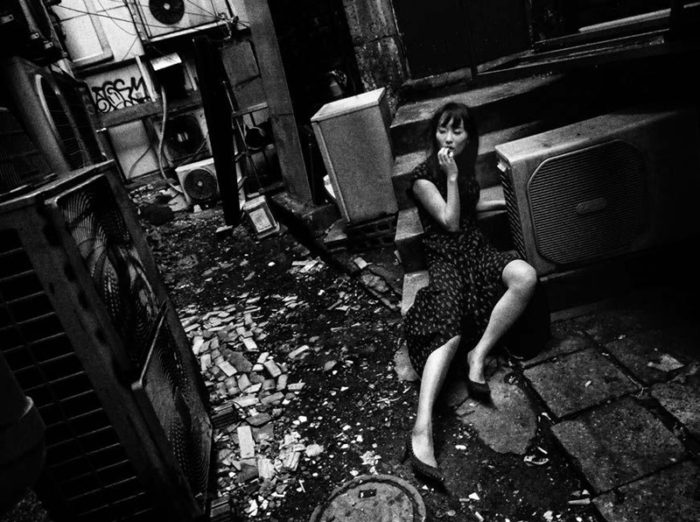

There is also a tie-in photo-book on sale featuring new-work by the great Daido Moriyama, who collaborated with Terayama on several projects back in the day.

Taken together, the two parts clock in at over 300 minutes. That sounds like an endurance test, but in fact time passes quickly as there are few longueurs and plenty of action-packed scenes, disparate narrative threads and a host of minor characters – abusive fathers, whorish mothers, psychos and street thugs and voyeurs – to hold your attention.

What you get for your money is part sports movie, part mythological drama, interspersed with erotic interludes and social and political satire and rapid montages of official and unofficial Tokyo. The boxing scenes are mostly realistic, with several of the actors looking useful inside the ring. Apparently one of the bit-players is even applying for a professional licence.

Yang gives a moving performance as the stuttering, socially inept ex-barber with the ring-name of “Barikan” (“Clipper”). Suda does a decent job as the rage-fuelled “Shinjuku Shinji.” The bromance between the pair is totally believable.

Is the film true to Terayama’s original text? Not at all, which is almost certainly the way he would have wanted it.

In the Afterword, Terayama wrote “For this novel I decided to use the techniques of modern jazz. The characters are the instruments, the vague story-line is the chord and everything else is filled in with improvised portrayals. The whole thing is totally haphazard, with nothing like a structure or plan… Most novelists decide on a theme in advance then reinforce it as they write, but in my case from the start I had no idea what was going to happen.”

The film fills in the empty spaces with highly produced pop music rather than jazzy solos, but the chord sequence is the same, the relationship between Barikan and Shinji, both damaged, but in different ways. The cripplingly shy Barikan takes up boxing as “a way to connect with people.” For the violence-prone Shinji, brought up in a facility for young offenders, it is a way to channel his inner turmoil.

Terayama’s Ah, the Wasteland first appeared as a magazine serialization in 1965, one year after the Tokyo Olympics. It’s no coincidence that the film version is set in 2021, one year after the next Tokyo Olympics.

Near-future Japan is not in great shape. The economy is back in recession. Suicide has become a huge social problem. Conscription has been introduced and the Self-Defence Forces are active in overseas trouble-spots. Terror bombings in central Tokyo are commonplace. Meanwhile, demonstrators throng the streets, protesting about student debt and other government policies.

In the novel, there is an onanistic entrepreneur who runs cut-price supermarkets. In the film he is a real estate developer working on projects to build luxurious, entertainment-packed funeral parlours, one of the few growth markets around. The students’ “Society for the Study of Suicide” in the novel morphs into a Suicide Prevention Festival complete with grimacing butoh dancers. The student leader, a shallow intellectual in the book, becomes a truly twisted piece of work

Lurking in the background is the trauma of the 3.11 triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown. Yoshiko, the thieving amateur hooker, has a new backstory. As a young girl she was brought up by her mother in temporary housing for quake victims, before leaving home for the big city. There is also a guilt-plagued employee of Tokyo Electric Power who is constantly on the brink of suicide.

If the film is darker than the book, it is also more populist, especially the generic soundtrack by punk-emo band Brahman. Yet Terayama himself was not averse to commercialism. Of the novel, he wrote “I’m not offering it to the literary world or critics or would-be writers…. Rather than having its literary merits debated, I’d prefer to have as many people read it as possible.”

He went on to puzzle about who the novel should be dedicated to. A relative or lover? Himself? A favourite racing horse? Writer Nelson Algren? Pneumatically-endowed Jayne Mansfield? In the end, he decided to dedicate it to “you the reader who paid your money and bought the book.”

In 1965 there were no sky-scrapers in Tokyo, no vast concrete plazas, let alone drones swooping through the air and news bulletins on giant screens. Yet in the world of the film there are other things that have scarcely changed at all. People still watch horse races and boxing matches and conduct dodgy transactions in dank coffee-bars and slurp ramen in tiny back-street noodle shops.

Above all, Terayama’s “neon wasteland” is still there, as alienating yet alluring as ever, home to new generations of Barikans, Shinjis and Yoshikos. Kabuki-cho is still Kabuki-cho and Golden-gai looks much the same as it would have when Terayama frequented its warren of bars fifty years ago.

That would have pleased him. “In fact, the novel has a co-writer-cum-critic,” he wrote. “Namely the Kabuki-cho district of Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo. That’s the place I like best in the world and trust the most and where I feel most at home.”