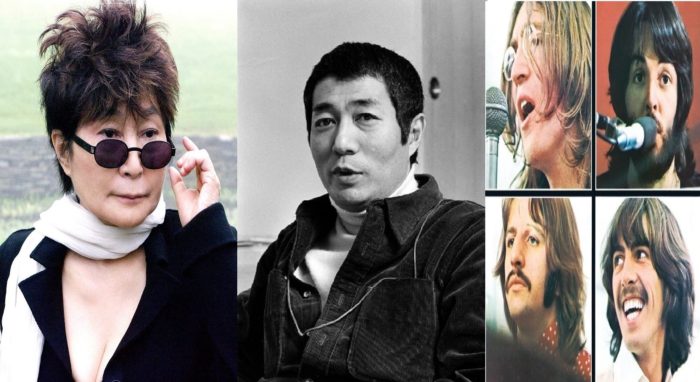

Yoko Ono and Shuji Terayama were very different people from very different backgrounds, but they had several things in common.

Both were of a generation old enough to be marked by Japan’s catastrophic wartime defeat and young enough to incorporate the experience into the new kinds of artistic expression that flourished in the 1960s.

Both were determined to break out of the constraints of the artistic milieu in which they has gained prominence – traditional tanka poetry in Terayama’s case, the neo-Dada avant garde in Yoko’s case.

Both were blasted by traditional critics – Yoko as a talentless charlatan and publicity-seeker, Terayama for plagiarism, even self-plagiarism. And both had the fireproof self-confidence and ambition to shrug off the criticism and get to where they wanted to go.

There were also similarities in their artistic philosophy. In her early 1960s manifesto, The Word of a Fabricator, Yoko’s opening line reads I feel a strange attraction to the first man in human history who lied.

As Midori Yoshimoto of New Jersey City University explains, Yoko saw fabrication / lying as intrinsic to the human experience. This strongly contrasted with the ideas of John Cage, Yoko’s mentor, who used random “chance operations” to reveal a supposed underlying, non-human “truth.”

Terayama also admired the art of lying and had little time for whatever lay outside human consciousness. In a famous aphorism, he declared My philosophy of life is that lies reveal human truth much better than reality. The reason is that reality would exist without humans, but without humans there would be no lies.

Both orchestrated elaborate jokes that played with notions of truth / lies. In 1970, Terayama presided over a funeral for Tooru Rikiiishi, one of the main characters in the wildly popular manga series Ashita no Jo (“Tomorrow’s Joe”). Seven hundred mourners lined up to pay their respects as incense swirled, candles flickered and a real Buddhist priest chanted sutras.

Yoko’s version was a fictional solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that “took place” in 1971. Without alerting the Museum, she placed advertisements in the Village Voice, had a catalogue printed and showed up on the prescribed day to film the crowd of would-be attendees, most of them mystified, some of them in on the joke.

The world is inside your head. You can make of it what you will. Terayama played with the concept throughout his career. Yoko took it much further.

Fabricating “John-and-Yoko”

The first edition of Yoko Ono’s book Grapefruit may have sold a minimal number of copies in 1964, but the second edition did a lot better six years later.

Issued by New York publishers Simon & Schuster, it had an introduction written by Yoko’s new husband that was short and to the point.

Hi, my name is John Lennon. I’d like you to meet Yoko Ono.

The book-signing event at Selfridges department store in London’s Oxford Street was mobbed by frenzied Beatles fans.

For Yoko, Grapefruit proved to be the gift that kept on giving. In 2018, she was awarded a writing credit for the song, Imagine, based on remarks that John Lennon made a few days before his death in 1980.

Actually, that should be credited as a Lennon-Ono song because a lot of it – the lyric and the concept – came from Yoko. But those days I was a bit more selfish, a bit more macho, and I sort of omitted to mention her contribution. But it was right out of Grapefruit, her book. There’s a whole pile of pieces about ‘Imagine this’ and ‘Imagine that.’ And give her credit now, long overdue.

John Lennon, interviewed by Andy Peebles of the BBC in December 1980.

Yoko’s influence on Lennon – artistic, political and personal – was transformative. Anti-war sentiment and feminism was in the air at the time, but both had been part of Yoko’s persona since the mid-1950s.

After the trauma of defeat and devastation in the Pacific War, pacifism was absolutely mainstream in Japan. Not so feminism, which was restricted to a tiny group of wealthy, artistically-inclined families who retained some trace of the liberated values of the Taisho Era (1912-1926). That was the milieu that Yoko was born into.

Lennon had already experimented with avant garde techniques on Tomorrow Never Knows, the last track on Revolver, which was recorded well before he knew of Yoko’s existence. Yoko’s influence took him much further. The White Album track Revolution No. 9, cooked up by the two of them, was probably the most famous piece of musique concrete in the world at the time, while also being the least listened to Beatles number ever.

Likewise, the John-and-Yoko “bed-ins” that entertained and outraged straight society derived directly from the avant garde performances Yoko pioneered in the late fifties and early sixties. Indeed, Yoko put on displays of “bagism” – the practice of climbing into a giant bag, either alone or with someone else, then stripping off and writhing around – with her second husband, Tony Cox, on the roof of their apartment in Shibuya, Tokyo.

Lennon referenced the concept in the lyrics of a song he wrote for his new group, the Plastic Ono Band, in 1968.

Everybody’s talking ’bout

Bagism, Shagism, Dragism, Madism, Ragism, Tagism

This-ism, that-ism, is-m, is-m, is-m,

All we are saying is give peace a chance

Yoko changed Lennon in a way that made it impossible for him to carry on as “Beatle John.” Likewise, Lennon changed Yoko in a way that made it impossible for to her remain an obscure avant gardist, putting on performances for handfuls of progressive intellecuals. In both cases, they were pushing on doors that were already half-open.

According to Midori Yoshimoto, Yoko’s pre-Lennon artistic stance was as follows: if you do a work of yours on the stage and the audience – all of it – walks out on you, then it’s a very successful concert, because that means that your work is so controversial, so far out that the audience could not accept it.

“Through Lennon,” Yoshimoto comments, “Ono learned about popular, mass culture, which was mainly sustained by the working class as opposed to the avant-garde of the upper middle class. The commercialism and populism of rock’n’roll music gradually made sense to her as a means of communicating with a large number of people.”

Shuji Terayama’s instincts led him in the same direction. He had already composed a macabre rockabilly song for an obscure Masahiro Shinoda film at time when The Beatles were still playing clubs in Hamburg.

Terayama was always happy to dash off a column for a weekly magazine or appear on TV at any opportunity. He even did a TV commercial for the Japan Horse Racing Association. Experimental films were interesting, but he wanted to make films and put on plays that would be surreal and challenging, but also fun and could be enjoyed by everybody. Likewise, he wanted to write songs that would be poetic, but also have mass appeal.

He didn’t want the audience to walk out. He wanted to pack them in. Even “the cheap seats in the peanut gallery” (= Tenjo Sajiki, the name he chose for his theatre troupe) would be filled. He saw himself not as a John Cage or a Jonas Mekas, but more like a P.T. Barnum of the avant garde.

Both Terayama and Yoko saw the unique opportunity that the rock’n roll generation provided and grabbed it with both hands.

To be continued.