In Havana’s Plaza Vieja (Old Square), a pavement artist produces a sketch of me containing two features that are purely imaginary. One is a nose long enough to stir a mojito; the other is a hat-band proclaiming “Cuba Must Survive.”

Cuba will survive, but which version? If you want a taste of Fidel’s workers paradise or the crumbling grandeur of the Cuba of Sinatra and Hemingway, you’d better move fast. Neither of them are long for this world.

After Marxism comes tourism, the only means for Cuba to pay its way in today’s world. When the Castros and their generation are gone, as they soon will be, the Americans will lift their embargo and flood back with their money and their brands. The effect will be, well, revolutionary.

The Plaza Vieja itself is a glimpse of the future, a clean Disneyfied construct straight out of a travel agent’s brochure. Foreigners are politely and efficiently separated from their money. The only locals visible are the ones bringing you food and drink or selling you a made-in-Bangladesh Che Guevara T-shirt or singing Besame Me Mucho, Guantanamera, and Oye Como Va in government-supplied funny hats.

My portraitist, who goes under the moniker of Picasso Vegas, wants money, specifically the CUCs (Convertible Units of Currency, pronounced “Cooks”) that foreigners are required to use. One CUC peso is worth twenty five domestic pesos.

This financial apartheid is more comprehensive than the dual currency system operated by the Soviet Union, in which the use of hard currency was limited to special stores for the party elite and foreigners. In Cuba all large shops denominate their wares in CUCs, while salaries are are paid in the soft domestic currency.

The result is everyone hungers for hard currency. According to Lazaro, our sharp-witted guide, there are only three ways to get hold of it – through tips, scams or money transfer from overseas.

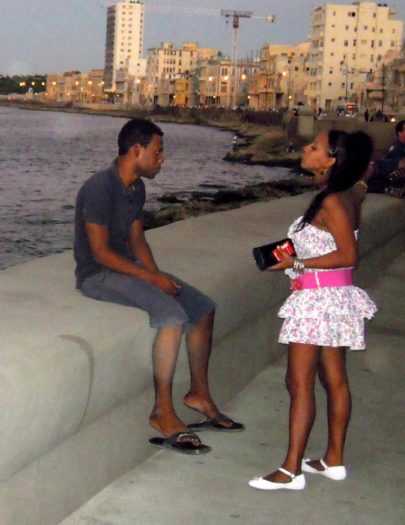

In the Plaza Vieja operators like Picasso are government-authorised. A few cops and security personnel hang around to prevent any overspill of unofficial scammers from nearby Obispo Street, an edgier tourist haunt which contains plenty of beggars by day and hookers by night and music all the time.

Lazaro is gloomy and up-front critical. “We have two worlds here,” he says. “Your world and my world. Ninety percent of commerce in Cuba is state-owned. We get ration coupons for our food, but they only last for twenty days of supply, after that we have to buy at high prices. We get meat twice a month, maybe a little more if we get sick. I have to live in the same place my whole life because it is not possible to buy or sell houses. We inherit them from our parents, who inherited them from their parents. The economy crashed after the fall of the Soviet Union, which was supporting our economy almost completely. My wife and I decided to wait for things to get better before having children, but we waited too long. Now it’s too late.”

Back on Obispo Street, a lady scammer approaches. “You want cheap cigars? I work in the cigar factory and I’ve got plenty. Cohibas that Fidel smokes, Montecristos that Che liked. I make a very special price for you.” I’m not interested in cigars, and anyway some of these bootleg versions are supposedly made from banana leaves.

“The place looks good to you,” Lazaro said. “But I have to live here, no way out. I’ve never been abroad. We have no access to the internet, but we can get emails from friends overseas. That’s how I know what happened to Gaddafi. We have three newspapers here. One writes government propaganda, the other two reproduce it in different words. All they said about Gaddafi was poor guy, such a shame.”

Revolutionary slogans and images are everywhere, portraits of Che covering the sides of apartment blocks, hasta la victoria siempre on posters in shop windows. On a mural near the Museum of the Revolution the holy trinity of Fidel, Che and Camilo Cienfuegos huddle in fraternal solidarity. A few yards away is the Spanish Embassy, where people with Spanish connections line up for visas. Pouting from its wall are the sultry features of Penelope Cruz.

“From school onwards we get bombarded with slogans,” Lazaro says. “Slogans about dying for the revolution, dying for socialism, everything about dying. What about living?”

We take a ride in a classic car, a mid-fifties Buick, shocking pink, with huge tailfins and a shark-grin of a radiator grill. The chassis is superbly maintained, but the engine, we learn, is a Toyota. Hundreds of these cars ply their trade in central Havana, harvesting the tourist CUCs. The Buick has an impressive sound system, which blasts out rap and techno at bone-shaking volume. We get some Jay Z, some UK dubstep and a good selection of the Cuban-American rapper known as Pitbull.

Pitbull has a great version of Guantanamera, evoking the song’s raunchy origin as a seduction story, rather than the pious anthem popularized overseas by Pete Seeger. “Come on, baby,” Pitbull tells the guajira farm-girl. “You gotta catch up to the times.”

There’s music everywhere in this city, blaring from bars and restaurants, booming from cars, spilling from high windows. Son, salsa, rap, rumba, rock, mambo, bolero, jazz – marinating and melding into a single polyrhythmic roar.

A guy on the street with a saxophone has a hard luck story. His instrument is broken and he can’t afford to get it repaired. “I love Cuba, no love Fidel,” he says. Love for Fidel, or any interest in Fidel seems thin on the ground. Even so he stares at us from posters all over Havana bearing the slogan “53rd Year of Revolution.”

“That’s pathetic,” my son says. He’s in his early teens.

“What is?”

“Fifty three years. Fidel should let someone else take over, and not his brother. And he won’t let anyone leave the island. I hate him. He ruined Cuba.”

Even so the boy wants to buy a Che Guevara T-shirt or a Che souvie of some sort, on the grounds that the icon of a million bedsitters sports a cool haircut, ‘tash & beard. Not being a fan of the narcissistic Argentinian psycho (look into those eyes – scary!), I refuse.

“But you bought me a Genghis Khan T-shirt. He was much worse than Che, wasn’t he?”

He’s right, of course. An expert at lawyering his parents, he zeroed in like a Predator on the contradiction in my stance. Che’s tally of several thousand dead/tortured/disappeared – as recounted here by Alvaro Varga Llosa – is small potatoes compared to the continent-spanning depredations of the great Khan.

I come up with some special pleading of my own. In the first instance, Genghis has been dead and gone these eight hundred years. In the second he had some positive qualities – tolerance of religious diversity, belief in meritocracy, the organizational skills necessary to turn a small desert land into a military superpower. It is possible to discuss the management secrets of Genghis, but not of Guevara.

So went the special pleading. The reality is I can’t stand the kind of people who would wear a Che Guevara T-shirt, some of whom are in Havana right now puffing Montecristos and looking pleased with themselves.

An elderly scammer approaches and offers to swap a domestic peso bearing Che’s image for a convertible peso. That would give him 2,400% upside with no leverage required. Not even Lehman Brothers’ best & brightest could produce that kind of return on investment.

We do the Hemingway tour. Old Ernie knew how to live life to the full, at least until he smoked that shotgun. Two hundred shrapnel scars, boxing, bull-fighting, big-game hunting, Marlene Dietrich, Martha Gelhorn – hard to imagine Jonathan Franzen or Ian McEwan matching that. Some Hemingway scholars claim that hidden underneath the macho posturing were cross-dressing fantasies, a mother fixation and possibly a gay affair with Scott Fitzgerald (according to Zelda). Which makes the story even better. More life, more complexity, more mystery.

Hemingway’s association with Cuba spanned four decades. He wrote part of For Whom The Bell Tolls in Room 515 of the Ambos Mundos Hotel on Obispo, and was inspired to write The Old Man And The Sea by his fishing jaunts with his illiterate friend Gregorio Fuentes. In the Floridita bar, the legendary boozer claimed the house record of 16 daiquiris and had an unsweetened version of the drink named after him. Ava Gardner froliced naked by the pool of his villa in the hills, and it was there that Batista’s goons shot one of his dogs, causing him to up sticks until after the revolution.

Ambos Mundos means “both worlds,” which takes us back to Lazaro’s comment about the two Cubas, the Cuba of the foreigners and Cuba of the Cubans. Only one of Hemingway’s books is available in Cuba – The Old Man And The Sea, which is taught in high school. The rest have not been issued by the state publishing organ. Information control is porous by the standards of Cold War communist regimes, but US radio is jammed and writers in exile such as the late Guillermo Cabrera Infante are non-persons. Needless to say, messing about on boats as Hemingway and Fuentes did is proscribed to all except state-controlled tourist and fishing personnel.

We hear about the tragic story of two teenage stowaways who froze to death at 37,000 feet after hitching a ride in the wheelbay of a jet. They thought they were taking a 30 minute hop to Miami when in fact the plane was headed across the Atlantic to Gatwick. There was a happier ending for a woman who mailed herself to Nassau in small crate, equipped with just a cellphone and a bottle of drinking water.

“We are a nation of would-be emigrants,” says Lazaro tells us. “We all want to go.”

Not everyone agrees. Carlos, who takes us to a model commune in the Sierra Maestra hills, is a true believer in Fidel’s socialist vision. He shows us the forest of Cuban flags around the US Office of Interest in Havana. “One for each victim of US terrorism,” Carlos says and fills us in on the career of Posada Carilles and the Cuban version of Lockerbie, the downing of Cubana Flight 455. Posada does not sound like a nice man, but at least his mug is not to be found on any T-shirts, key-rings or mousepads.

In his spare moments Carlos studies a photo-book celebrating the Seven Wonders of Cuban Engineering. The most impressive is an aqueduct built in the late nineteenth century. Others include the Havana Bay tunnel and the cross-island highway, now riddled with potholes and fissures. The latest of the wonders, the Bacunayagua Bridge, opened a few months after the revolution.

The Castro regime, like its communist conferes, has built almost nothing of value – which is why the splendours of the pre-revolutionary past remain intact in a way that would be impossible in a successful emerging economy. When Fidel & Raul go, they go too.

Carlos has heard about the riots in the UK over tuition fees. Nothing like that in Cuba, he proclaims with pride. Education is free. He himself has degrees in engineering and law and speaks English, French and German, as well as Spanish. Even so Carlos has never worked as an an engineer or a lawyer. That wouldn’t make sense for him, as he freely admits. Instead he works as a guide, chasing the CUCs generated by tourists from Europe , Canada, and, increasingly, China and Latin America.

The commune is picturesque, eco-friendly and totally unviable as an economic unit, a fact that became apparent only after the Soviet subsidies evaporated. The Castro government’s plan to revive coffee production in Cuba came up against the hard realities of the market economy – competition from low-priced beans produced by large-scale farms in Brazil and Colombia. Production is now 90% below the Batista-era peak. The coffee you drink in the cafes and hotels of Havana is imported, as are the dairy products, the tropical fruit and the ham and sausages.

As for the Sierra Maestra commune, today it subsists on tourism. Foreigners pay improbably high prices to watch their kids go whizzing on zip-wires over the roofs of a shattered socialist dream.

We visit Varadero, a finger of land pointing out into the Gulf of Mexico, serviced by its own airport and dotted with dozens of vast multi-coloured concrete carbuncles. These foreign-owned hotels are filled to capacity. For this is no longer Cuba. It is an outpost of Resortland, a fast-expanding empire of sea, sex and sun that has thriving colonies in Thailand, Bali, Greece, Mexico, Spain and elsewhere.

Europeans & Canadians bask like lizards at the side of the hotel pool, hell-bent on losing their winter palor. The Chinese eat and laugh and flaunt their bling. A tattooed Brit absorbs the latest about Man U from the back page of The Sun. A gossip mag headline confirms that the marriage of Russell Brand and Katy Perry is now deader than Che.

There are dazzling white catamarans to whisk you to sun-kissed islands, dolphins to swim with and photos to commemorate the occasion, all-you-can eat buffets and all-you-can-drink beach-bars and a mini-club to keep the kiddies busy while the parents play. The CUCs flow like mojitos. The evenings pass in a blur of mambo-ing midriffs and rumba-ing rumps.

The local staff handle everything superbly. They are courteous, funny, sexy, charming, thoughtful, diligent.

At Varadero we have seen the future and it works. It isn’t pretty, it isn’t classy, and it won’t please literary scholars or anti-globalism activists. But it’s the only deal on offer, and there’s plenty in it for both sides.

In the words of Pitbull, you gotta catch up to the times.