Published in Nikkei Asia July 6th 2023

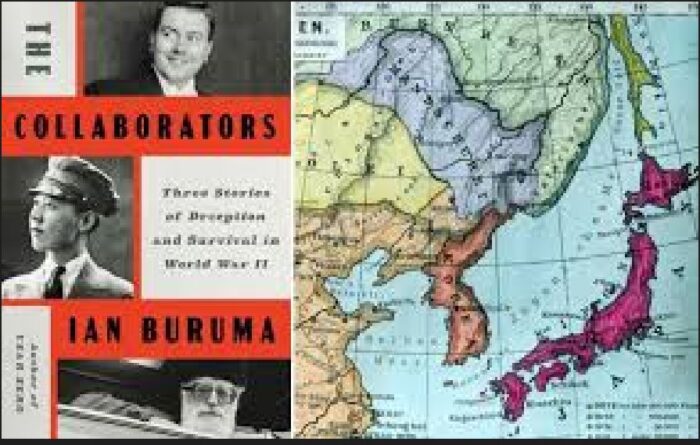

Ian Buruma has the rare skill of bringing together seemingly disparate characters and events in a way that sheds startling new light on well-worn themes.

Of his many works, my personal favorites include “A Tokyo Romance,” a memoir of his six-year sojourn in 1970s Japan, his excellent novel “The China Lover,” and “Year Zero: A History of 1945,” which describes the bloodshed and chaos that continued in corners of Europe and Asia long after the official end to World War II. Buruma has also published many other books that are well worth seeking out.

His latest is “Collaborators: Three Stories of Deception and Survival in World War II.” The title is provocative. When artists and musicians collaborate today, the term has a positive connotation. But in the context of World War II in Europe, it has a totally different resonance, summoning up images of young French women being brutalized by kangaroo courts for having sexual relations with German troops.

The word signifies disgrace and always describes those who consorted with the enemy, which is to say our enemy. Perhaps the Viet Cong had a similar word to describe the Vietnamese women who had sex with American soldiers in the Vietnam War, but we do not hear about them.

Much of this relates to the special status of World War II in our consciousness which, unlike all previous European wars, was not about national interests but the survival of Western civilization in its contemporary form. In today’s world of ever more fiercely disputed narratives, one of the few propositions that commands universal assent is that the Nazis were evil and it was a good thing that Germany lost the war. That is why the subject generates so many films, books and memorial events compared to more recent conflicts in the Korean peninsula, Vietnam, the Falkland Islands and the Persian Gulf. It helps us feel good about ourselves.

The 1941-1945 war in the Pacific carries nothing like the same moral heft, being more like a traditional clash of interests. The Western colonial powers had dismantled China in the 19th century and Japan’s national strategy was to make sure it did not undergo the same humiliation. Its early steps to create an imperial space in its immediate environs — defeating China and Russia in battle and annexing Taiwan and Korea — were warmly applauded by the Western powers.

As art critic Tenjin Okakura wrote shortly after the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, the West regarded Japan “as barbarous while she indulged in the gentle arts of peace but calls her civilized since she began to commit wholesale slaughter on Manchurian battlefields.” Only when Japanese ambitions began to threaten the interests of the dominant powers in East Asia, all of whom were white, did the mood change.

Buruma starts his narrative in the early years of the 20th century, recounting the life stories of three individuals, all of whom were displaced from their countries of origin by the revolutions and regime collapses of the era. Thus, their allegiances were tangled from the start.

Frederyck Weinreb, the darkest figure, was a Hassidic Jewish immigrant to The Netherlands who scammed other Jews by pretending to save them from the death camps, for a fee, while betraying some of them to the German occupiers. Found to have been responsible for 70 deaths, he lived on until 1988.

Felix Kerstner, who died in 1960, is the most representative. A citizen of Finland, which had declared itself neutral, he had been the personal masseur of Heinrich Himmler, a leading Nazi. In the post-war world, that was not a good look so he engaged in some drastic CV padding. Thanks to his persuasion, he claimed, Himmler had scrapped a plan to move the entire population of The Netherlands to Nazi-controlled Eastern Europe. Kersten was decorated by the Dutch Royal family, but in fact, no such plan existed. He had made the whole thing up.

Kersten’s feat of self-exonerating mythmaking was simply a bolder and more imaginative version of many such evasions and cover-ups. Indeed, as Buruma notes, Charles de Gaulle, leader of the wartime Free French forces and a post-war president of France, created a national myth in which most French people were in the resistance and were instrumental in freeing themselves from Nazi oppression. When film director Louis Malle made “Lacombe, Lucien”, a 1974 film that portrayed French complicity in the Holocaust, there was a furore and he ended up leaving the country.

The odd one out of the trio is Yoshiko Kawashima, also known as Dongzhen (Eastern Jewel), her Manchurian nickname. She is the only female, the only Asian and the only one not to survive her wartime experiences. The term “collaborator” seems a stretch too, since she was brought up in a Japanese household from the age of six and, as the child of a Chinese Qing dynasty aristocrat, felt no bond to the Han Chinese government that had toppled the Manchurian Qings. Her story is by far the strangest, the most colorful and the most poignant.

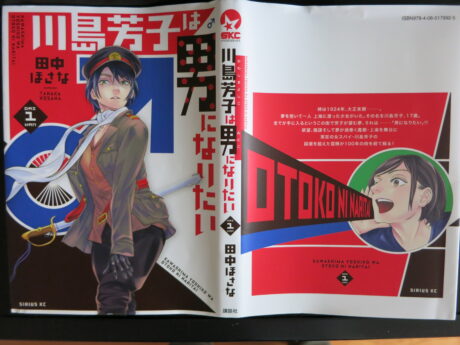

Manga version of the Yoshiko Kawashima story

At the time, Japan was a role model for many Asian intellectuals and activists, who were dazzled by the country’s leap from feudalism to modernity in a half-century. So it is no surprise that Yoshiko’s father sent her to a Japanese school in Manchuria, where he was living. It was slightly more surprising that he would pass her on to a Japanese friend as a kind of present.

Only slightly, because the nuclear family was far from established in either country. Wealthy people had a lot of children. The entrepreneur Eiichi Shibusawa, who is about to grace Japan’s new 10,000-yen banknote, had 38, including a few from his wives. Offloading your children to distant relatives or acquaintances and never seeing them again was by no means rare. It happened to the poet Mitsuru Kaneko and the novelist Yasushi Inoue. No doubt, uncountable numbers of children of distressed farmers would have experienced similar or harsher fates.

In Buruma’s telling, Yoshiko reveled in the image she created, yet the reality was extraordinary enough. The Japanized ex-princess became a gender-fluid cross-dresser who referred to herself as “boku,” a word that Japanese males use to mean “me.” Nonetheless, she had a large number of liaisons with important political and military men, which earned her the sobriquet “the Mata Hari of East Asia.”

After a brief marriage to a Mongolian aristocrat — unconsummated, according to Buruma — she moved to Shanghai, where she seduced the son of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Chinese republic, and obtained important secrets from him. Back in Manchuria, now a de facto Japanese colony, she gave rein to her Joan of Arc complex, leading a group of reformed bandits into battle.

She also became the equivalent of an idol singer, releasing a series of hit songs recorded in Manchuria’s state-of-the-art studios. As time went by, she became more unpredictable and more critical of Japanese activities on the mainland. She also developed a liking for what would now be called “hard drugs,” though there was no such concept in those days.

The fact that she was executed by Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang Chinese nationalist forces n is an indirect tribute to her stature. The two European collaborators were basically myth merchants. All they did was lie, though Weinreb’s lies had fatal consequences for others. Yoshiko was an active participant in world-shaking events — as a spy, possible agent provocateur and symbol. She faced the firing squad in 1948, at the age of 40.

Buruma percipiently relates the 1920s and 1930s to our own time, citing a general cultural entropy in which chancers and conspiracy theories thrive. He is right. Conspiracy theories take hold and chancers get their chance when nobody knows what to believe. And sometimes, there really are conspiracies — or at least crucial decisions taken far from the public eye. To put it another way, the larger cause of the rot is a general collapse in confidence in elites.

That was very much the case for Japan 100 years ago as governments and business leaders deliberately deflated the economy through the 1920s, culminating in the disastrous decision to rejoin the Gold Standard in 1930. The upshot was the Showa Depression which led to the immiseration of farmers in northeast Japan, daughters being sold into prostitution, domestic terrorism, a bloody putsch that paved the way to military government and the full-scale invasion of China.

Through this entire period, Japanese financial policy was closely supervised by the Morgan Bank and Thomas Lamont and Company. Mark Metzler, professor of history at Washington University, had this to say about Lamont: “Were a populist conspiracy theorist of the time to have wholly invented a personification of the international money cartel that pulled the strings of the governments of the world, he could hardly have done better than the actual Mr. Lamont.”

If Japanese officials had listened instead to the British economist J. M. Keynes, whose ideas about the use of demand management to stabilize economies were already known to progressive thinkers such as the journalist and politician Tanzan Ishibashi, there might never have been a Showa Depression, with all its disastrous consequences. In which case, world history would have been very different and today Yoshiko would be known only as an LGBT pioneer who lived to a ripe old age.

Would she have wanted that? Probably not.