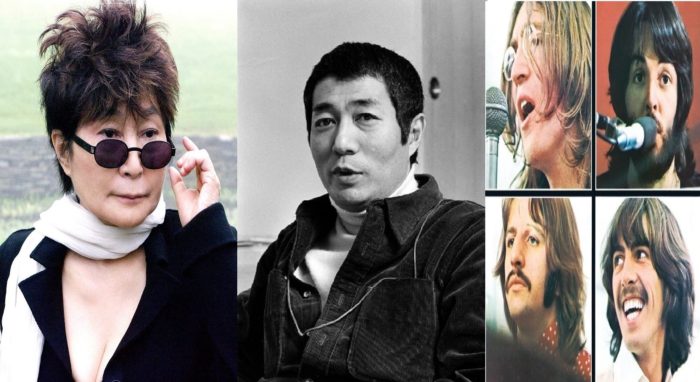

In late June 1966, Shuji Terayama was one of many Japanese celebrities who showed up at the Budokan martial arts hall in Tokyo to experience the hottest event in the world at the time – a live concert by The Beatles.

Novelist Yukio Mishima spent much of the time examining the hysterical response of young women in the audience, which he found mystifying. Fellow novelist Shusaku Endo invited the leader of a flower arrangement school and actor Hiroshi Akutagawa, son of the famous author Ryunosuke Akutagawa, to accompany him.

Endo likened the Beatlemania that he witnessed to the religious ecstasies in American Pentecostal churches, but neither writer said much about the music or the significance of the Beatles themselves.

Terayama was thirty one at the time, which made him ten years younger than Mishima and twelve years younger than Endo. He was already a Beatles enthusiast, as he made clear in an article penned a few weeks earlier for the Weekly Yomiuri magazine. The Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan and the world’s largest daily newspaper at the time, was the sponsor of the concerts.

In that piece, Terayama displayed an impressive command of Beatles lore while indulging in his fixation with death. Early Beatles member Stu Sutcliffe, who had died from a brain hemorrhage at the age of 21, had “fallen like a bird from the sky.” The pun-loving Terayama also turned the “four man” group into a “dead man” group (“four” and “death” are homonyms in Japanese).

Terayama identified strongly with the band’s irreverence and iconoclasm. He noted that John Lennon had been brought up in a fatherless household, as he himself had. The melodic, McCartney-esque side of the Beatles – Yesterday and Michelle were already much loved in Japan – did not fit his agenda and made little impression on him.

Terayama ended his article with an Allen Ginsberg-like rush of images.

In a few phrases Beatles music is

A bath boiler exploding in an old peoples’ home.

A love-letter scribbled on a school blackboard.

Pissing all over the grass in a churchyard.

The sound of someone shaving with an electric razor

when you’re in the bath.

Forty four tomcats moaning with lust.

The sound of a girl’s skirt being ripped to shreds

by a hairy hand.

The Miami sea flowing out of a beer bottle.

A limousine with no brakes driving off a cliff.

A new piping-hot sound extracted from the cut throat of an opera singer.

The screech of a cat electrocuted by a neon sign.

The melody of buckets of red paint being splattered on an advertising billboard.

A spinster’s pelvis being shaken in an earthquake.

The sobs of a middle-aged man with a violet clamped between his teeth.

And the sound of a sports car hurtling down the highway of our times.

Terayama was hurtling down that highway too, but driving with a lot of care and concentration. Although he loved the concept of rock music, he was no rocker himself, either in personal style or taste in music. The hit songs that he wrote for Carmen Maki, Maki Asakawa and other singers – with music composed by Michi Tanaka or other collaborators – were usually in a folk, chanson or enka style that would have wide appeal.

Still, he continued to invoke the spirit of the Beatles. The inside of cover of his 1967 publication Throw Away Your Books and Run Into the Streets, a compendium of essays and provocations, featured images of the Fab Four imprinted with lipsticked kisses.

As late as 1979, long after the Beatles had split up and just twelve months from the murder of John Lennon, Terayama quoted a Beatles lyric in No More Easy Life, the theme song that he contributed to the Yoichi Higashi film of the same name.

If someone understood the loneliness of losing love

I’d pretend to be drunk and grab his shoulder

And sing “Come Together”

Back in June 1966, the Beatles were about to release Revolver and make their last appearance in front of a live audience, in August at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park.

John Lennon was five months away from encountering an avant garde artist called Yoko Ono at the Indica Gallery in London.

Of course, Terayama knew all about her already.

To be continued