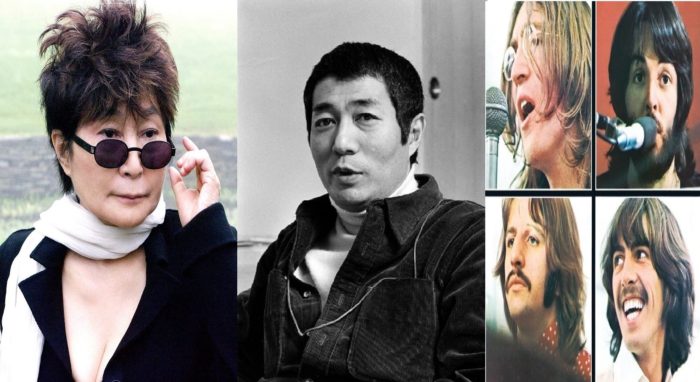

Probably the first time Shuji Terayama clapped eyes on Yoko Ono was when she was draped across John Cage’s piano during his legendary concert at the Sogetsu Art Center in the autumn of 1962.

Yoko’s relationship with The Beatles and marriage to John Lennon made her the best-known Japanese person in the world and has tended to erase her pre-John accomplishments. But in October 1962, The Beatles were an unknown group about to release their first single, Love Me Do, and Shuji Terayama was an obscure tanka poet and writer of radio plays.

Yoko, though, was an established figure in avant garde artistic circles, a pioneer of the international Fluxus movement and an acquaintance of Cage, Andy Warhol and underground film-maker Jonas Mekas. Indeed, she was married to Cage’s most prominent Japanese disciple, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and the two of them were instrumental in arranging his concerts in Japan.

Yoko herself had already performed experimental music at the Carnegie Recital Hall in New York and, together with minimalist composer La Monte Young, ran an avant garde salon in Lower Manhattan whose guests included Marcel Duchamp, the venerable godfather of conceptual art.

Equally compelling, from Terayama’s point of view, was the powerful persona Yoko had developed, part shaman, part trickster. As she flitted from genre to genre – experimental movies, musique concrete, performance art, the absurdist “instructions” in her book Grapefruit – it was hard to define who or what she was.

SMOKE PIECE

Smoke everything you can.

Including your pubic hair.

From Grapefruit, by Yoko Ono.

Terayama became a multi-media presence too, moving from poetry, short stories and plays to experimental films with little or no dialogue and street theatre events, such as Knock, which featured large scale audience participation.

Although a prolific writer throughout his life, he also shared the Fluxus / Dada aspirations of going beyond verbal communication and breaking down the barriers between artists and audiences. Like Yoko, he was a natural provocateur. Shock and humour were always part of the package.

In later years, Terayama was to claim that his profession was “being Shuji Terayama.” Yoko Ono was a trailblazer in the art of self-construction. Her profession has always been “being Yoko Ono.”

Her conceptual art began on a small scale with on-stage happenings such as the proto-feminist Cut Piece, in which members of the audience were invited to cut off her clothing, piece by piece, while she sat as impassive as Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy.

Eventually, she dispensed with the stage and the gallery. Instead, she developed open-ended real time performances such as “bed-ins,” the creation of “John and Yoko” and, some would say, the break up of The Beatles.

Another aspect of Yoko’s persona that would have attracted Terayama was her unembarrassed, self-edited Japanese identity. Many well-known Japanese artists and intellectuals seemed burdened, even anguished, by a self-conscious Japaneseness that constantly needed to be explained and defended in Western terms. Indeed, the inner conflict thus created is the great theme of much twentieth century Japanese literature.

Yoko didn’t seem conflicted. She operated with ease in the English language – something that Terayama never managed – but did not seem at all Americanized.

Some of the pieces in Grapefruit are influenced by Zen Buddhism, but she seems to have been exposed to it in the United States, as Cage was, by attending the lectures of the great Zen proselytizer D. T. Suzuki. At the time, Zen was both a Japanese thing and an avant garde thing, with little apparent contradiction.

THROWING PIECE

Throw a stone into the sky high enough

So it will not come back.

From Grapefruit, by Yoko Ono.

Yoko’s uniqueness and separation from the Japanese mainstream makes her one of the few Japanese – Akira Kurosawa is another – whose name is often written in the katakana script, rather than with conventional kanji Chinese characters. Yet she was also comfortable with her Japanese roots, as expressed in the Chinese characters for her given name, which mean “child of the ocean.” Presumably, she mentioned that to John Lennon, who incorporated the reference into the White Album song Julia, addressed to his dead mother.

Half of what I say is meaningless

But I say it just to reach you, Julia,

Julia, Julia,

Ocean child calls me

Terayama was not constrained by Japaneseness either, though he did play up his roots in the remote north of Japan’s main island as a badge of outsider status. He saw himself as part of a wider global underground / avant garde movement. In the midst of setting up his theatre troupe, he travelled to New York to discuss projects with Ellen Stewart, the founder of the La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club.

During the 1970s, Terayama spent many months a year overseas with his Tenjo Sajiki theatre troupe, which went down well at adventurous art festivals. His penultimate film, China Doll, was a French production with a multinational cast including Klaus Kinski. His final film, Farewell to the Ark, was a Japanese re-imagining of Gabriel Garcez Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Yoko’s example would have offered Terayama a glimpse of the avant garde’s potential, but also its limitations. The random musical experiments of John Cage and others were destined to remain a minority interest, likewise most of the underground films of the era.

Such productions tended to be a lot more interesting to discuss and write about than to experience directly. Yasunao Tone, founder of Group Ongaku, claims that a La Monte Young concert in New York for nine musicians had an audience of just four who the musicians encircled to stop leaving. The first edition of Yoko’s Grapefruit was privately published in 1964 with a run of 500 copies, priced at six dollars. Today copies change hands for tens of thousands of dollars.

Terayama’s notion of the avant garde was at odds with Cage’s austere elitism. By nature and inclination, he was a populist who loved Ken Takakura’s gangster movies, freak shows, pop music, jazz, boxing and baseball. You were more likely to find him at the racetrack than meditating at the Zen garden in Ryoanji Temple, as Cage did in 1962.

Was there some way to combine the avant garde spirit of subversion and boundary-breaking with fun and mass accessibility?

Yes, there was – and Yoko Ono got there first.

To be continued.