Published in Nikkei Asia 22/9/2022

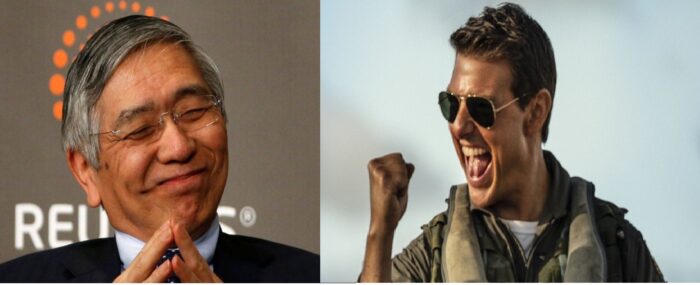

It’s not just Tom Cruise reprising the title role in Top Gun: Maverick. There is a distinctly 1980s vibe to the currency markets these days. “King Dollar” is blasting through the skies, leaving every other currency gazing in awe at its contrails.

Worst affected so far is the yen, which has fallen from 115 to the dollar at the start of the year to 144 recently. But remember what happened all those years ago. The Plaza Accord of 1985 triggered a dizzying plunge in the dollar that took the currency down 50% against the yen and the West German Deutsche Mark.

With economic conditions still difficult after Plaza, the dollar stayed flat on its back for nearly ten years. Even a Top Gun needs a long period of convalescence after a crash landing.

Foreign exchange markets move around much more than they should. The economic fundamentals of countries, especially large mature countries, change only slowly but the markets are in a constant state of flux, often driven by speculation about government policy, interest rate moves and other transient factors. Trend-following and massive overshoots are the rule, not the exception.

What should be the most important fundamental factor is the purchasing power of a currency over time. In other words, what you can buy for your money. All other things being equal, the currency of a country with high inflation should decline relative to the currency of a country with low inflation, thus preserving the balance in purchasing power. If that doesn’t happen, the high inflation country will lose competitiveness as prices rise.

To put it another way, the external value of a currency should mirror its internal value.

That is the theory. Market reality is very different. The yen has been weak this year, not just against dollar, but even against the struggling British pound and euro, even though all three Western economies are suffering from near double digit inflation. At 3.0%, Japanese inflation is extremely placid in today’s world, even more so than famously disciplined Switzerland (3.5%) and Singapore (7%).

The result can only be a large competitiveness gain for Japan. If sustained over time, this would result in higher profit margins or larger market shares for exporters, re-onshoring of production by Japanese companies, a greater likelihood of foreign companies choosing Tokyo as a regional hub and the mother of all tourist booms – assuming that all Covid restrictions are scrapped.

Historically, a super-strong dollar has been destructive, particularly to emerging economies, because it swells the value of dollar-denominated debt issued by foreign corporates and governments when translated into local currency terms. Sometimes this leads to a death spiral as the higher debt causes the currency to slump further, which raises the debt burden even more in local currency terms.

For Japan, exactly the opposite applies. It is the world’s largest creditor nation, and a declining yen causes the value of its treasure trove of dollar-denominated assets to soar.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has so far been able to weather speculative attacks on the yen and the Japanese bond market because, in stark contrast to George Soros’ coup against the unsustainably overvalued British pound in 1992, the BoJ’s current policy settings are doing no obvious damage. In market speak, the weak yen is not a “pain trade”.

Of course, if Japanese inflation were to take off in a meaningful way, that would be a different story. At the moment, though, inflationary pressures in Japan are largely imported and there is little sign of an escalation in wages and salaries, as seen in the U.S. and elsewhere. More than likely, 2023 will see a significant drop-off in CPI inflation as the year-on-year comparisons flatten out.

Indeed, Japan’s GDP deflator – a gauge which measures all prices in the economy, not just those paid by consumers – has been in negative territory for six quarters in a row.

Kuroda’s term as BoJ Governor will end in the spring and his successor may well tweak policy settings, but a full-scale reversal is unlikely. In 2013, the BoJ undertook to achieve a 2% inflation target “sustainably”. It has yet to succeed. Even if the target is halved, which is one possible face-saving measure, some stimulative policies will likely continue.

Even so, there may be turbulent times ahead in the currency markets. The Japanese monetary authorities may find themselves with a familiar problem on their hands – how to cope with an excessively strong yen. They may even find themselves battling deflation again, bizarre as that may seem in today’s world.

There are two reasons why this could happen. The first is fundamental value. The Japanese yen has spent most of the last 40 years being grossly overvalued. Now it is grossly undervalued, to the tune of 43%, according to the OECD’s estimate of purchasing power parity versus the dollar. In other words, the yen is as almost as undervalued now as it was overvalued at the maximum in 1995.

What that means in practical terms is illustrated by the huge gap in wages that has opened up when viewed in common currency terms. For the first decade of this century, average wages in Japan and the United States were roughly the same. Today the average wage in the U.S. is $74,100. At current exchange rates, the average Japanese wage has fallen to $29,900.

Have U.S. workers suddenly become twice as productive as Japanese workers? Absolutely not.

Fundamental value is a notional anchor, but currencies can diverge from fair value for years, decades even, which was the case for the yen from 1987 to 2013. More important is the political backdrop, which is to say the interests of the United States, the prime mover of the yen dollar relationship and other sensitive exchange rates.

How overvalued is the dollar? And how undervalued is the yen? The answer to both questions is the same: very. The dollar / yen exchange rate was 140 in 1990, as it is now, but a 2022 dollar is nothing like a 1990 dollar. US consumer prices have trebled in the intervening period. Meanwhile Japanese consumer prices have risen just 10% in total. A 100 yen in 2022 is not much different from a 100 yen in 1990 in terms of what it buys.

The best way of capturing the relative purchasing power of currencies is through the “real effective exchange rate” which takes into account the effect of inflation and measures a currency not against just one other currency, such as the U.S. dollar, but against a basket of currencies that reflects their importance in trade.

On this measure, the decline in the yen started in 1995. The depreciation since that peak already amounts to 60%, taking the Japanese currency back to where it was in 1971. Where we are now looks a lot more like the end of a weak yen cycle than the beginning.

As for the ascent of the dollar, it is already long in the tooth in real effective terms, having kicked off in 2014. Moreover, over the entire 51-year era of floating currencies, it has only been higher than it is now 3.6% of the time: between April 1984 and February 1986. That, of course, was just before the orchestrated collapse of the dollar.

Back then too, the Federal Reserve was combatting structurally high inflation, yet America’s loss of competitiveness, worsened by the rampant dollar, could not be endured for long. It was the “free market” administration of Ronald Reagan that initiated the currency stitch-up at the Plaza Hotel, as well as a raft of protectionist export quotas and “voluntary” restraints aimed mainly at Japan.

The world has changed greatly since then, but the political calculus has not. It is just a question of time before economic weakness takes over from inflation as the number one problem in the eyes of the American public and politicians. When that happens, keeping the dollar high in the sky will require a feat out of another Tom Cruise movie – Mission Impossible.