Published in Japan Forward 03/08/2022

Werner Herzog is one of the great film directors of our time. His golden period was in the 1970s and early 1980s when he created such dark masterpieces as Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), all featuring the unsettling presence of German actor, Klaus Kinski.

Resident in the United States for many years, Herzog has also directed dozens of documentaries and many operas and has appeared as a German-accented villain in Jack Reacher (2012) and in a Star Wars TV spinoff. In 2008, he made the highly entertaining Bad Lieutenant, set in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and starring a rampant Nicholas Cage.

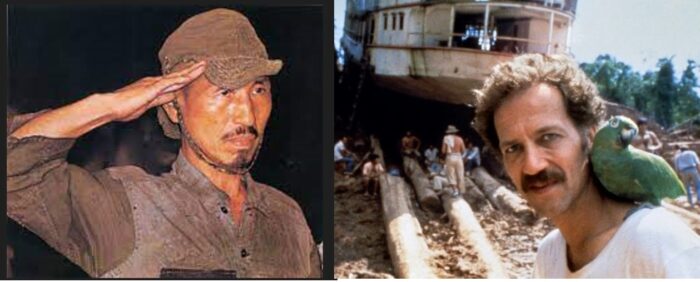

Now, at the ripe old age of 79, Herzog has published his first novel. It is as idiosyncratic as you would expect. Over 132 slim pages, he tells the story of Hiroo Onoda, the Japanese soldier who refused to accept that World War 2 was over and continued patrolling a mountainous island in the Philippines until 1974.

Herzog appears to have harboured an obsession with Onoda for a long time. In the late 1990s, when he was in Tokyo to direct an operatic version of Chushingura, the tale of the 47 heroic samurai, he actually met Onoda. In fact, Herzog claims that he declined an invitation from the Emperor, possibly the worst faux pas it is possible to make in Japan, in order to meet Onoda.

Together the two men visited Yasukuni Shrine, where Onoda, long considered legally dead, had been enshrined along with the other 2.5 million people, stretching back to the mid-nineteenth century, who had given their lives for the fatherland.

Herzog was aware that the shrine was controversial, but accepted the invitation, thinking “who am I anyway to allow myself the luxury of such reservations, coming as I do from a country that has brought such horrors on other countries and peoples.”

At the shrine, a priest produced a flat carton containing the tattered remains of the uniform that Onoda had worn for thirty years in the Philippine jungle. As Herzog writes, “Onoda asked the abbot if he would let me take the uniform in my hands. I bowed, and the abbot laid it in my formally outstretched arms. The abbot exchanged a few words with Onoda and encouraged me to unfold the uniform and to feel it. I did so with extreme care.”

Did any of this actually happen? The book, remember, is a novel – and Herzog is known for his concept of “ecstatic truth” which can be reached “only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.” He cares very little for “the truth of accountants,” meaning facts. Onoda died in 2014 at the age of 91. Whatever happened between the two men, if anything, is transmitted to us via the consciousness of Herzog.

The story proceeds through a series of short, strongly visual episodes which describe the amazing measures Onoda employed in order to evade capture. He and his two comrades would walk backwards for considerable distances to confuse pursuers. Once, his leafy camouflage was so effective that a Philippine soldier on a march through the jungle stepped on his toe. But Herzog’s main interest is in Onoda’s mind, his “fever dreams”, and the new reality he creates through sheer force of will.

Crickets scream at the cosmos. Among the terrors of night was a horse with glowing eyes smoking cigars… The jungle bends and stretches like caterpillars walking, uphill and down. The heron when cornered will attack the eyes of its pursuers. A crocodile ate a countess…

Needless to say, there is a lot of Herzog in Herzog’s Onoda, but then there is a lot of Herzog in all the obsessional characters that people his best films. Even the protagonist of the documentary Grizzly Man (2005), an American hippie who treats grizzly bears in the wild like cuddly pets, has a kind of crazed nobility. The reality that he has constructed is fragile – but he knows that and is willing to accept the horrific consequences.

Indeed, obsession and refusal to kowtow to humdrum reality are key elements in Herzog’s own film-making process, as demonstrated by his greatest work, Fitzcarraldo. The story is of an opera-loving adventurer living in the north of Peru during the short-lived rubber boom of the early twentieth century.

Fitzcarraldo, as the Irish protagonist is known, resolves to build an opera house in the small town of Iquitos in the Amazon basin and invite the great tenor Enrico Caruso to perform. In order to raise capital for the project, he attempts to procure rubber from an unexploited and highly inaccessible area of the jungle. That requires transferring a 3-storey 300 ton ship from one river system to another by hauling it over a hill.

Herzog could have filmed the whole movie in Iquitos and used modern technology and clever camerawork to simulate the ship being lifted over a hill. Instead, he chose to film in the jungle and operated a mechanical pulley and winch system that could have been used in the early years of the century.

The Burden of Dreams (1982), Les Blank’s documentary about the making of the film, shows the engineer responsible quitting on the grounds that there was only a 30% chance of success and that five or six of the staff, all local tribespeople, might die.

In the end, there were no fatalities during that mud-spattered battle to defy the force of gravity, but during the four years spent making the film people died in light aircraft accidents and limbs were amputated because of snakebites.

Herzog had other troubles too. Originally, the main character was to be played by Jason Robards, but the America actor came down with amoebic dysentery after 40% of his scenes had already been shot. Mick Jagger had been cast as Fitzcarraldo’s sidekick, but his scenes – which are surprisingly convincing – had to be removed too.

When Herzog flew back to Germany to explain the situation to his backers, he was asked whether it was really worth reshooting all these sequences. His reply: “if I don’t, I would be a man without dreams.” The implication was that life without dreams, even absurd or dangerous “fever dreams”, was hardly worth living. In effect, Herzog himself became Fitzcarraldo.

Both triumphed in their own way. Fitzcarraldo ends up welcoming a boatful of opera stars, including the great Caruso, to a concert hall in a small town in north Peru. The film Fitzcarraldo was chosen by Akira Kurosawa as one of his top one hundred movies and has been garlanded with praise and awards.

Even some of the setbacks turned out to be beneficial. Kinski’s intense performance was far superior to Robards’ low-key Hollywood approach.

If a film brought out Herzog’s inner Fitzcarraldo, the novel brings out his inner Onoda. “Onoda and I straightaway struck up a relationship,” he writes. “We found much common ground in our conversation because I had worked under difficult conditions in the jungle myself.” Herzog feared the jungle, but was also fascinated by it. In later life, he would return to the Amazonian jungle and hold film school classes there!

The conditions of war and contemporary political debate held no interest for him. In his book, he states baldly that there are no reliable numbers of the Philippine soldiers and civilians who may have died in clashes with Onoda’s three man unit. For this was no game of hide and seek. Onoda considered himself to be a guerrilla fighting behind enemy lines. Indeed, his two comrades were both shot dead in firefights.

Apart from Herzog’s novel, last year a young French director, Arthur Harari, released an enthralling cinematic version of the Onoda story called “Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle.” The fascination is the same. In effect, Onoda rejected the accountant’s version of reality and opted for the ecstatic kind. He constructed a dream and lived inside it for thirty years.

That feat of extreme imagining seems to stand apart from the context of Japan’s lost war, now fading into the history books, and has become an inspiration to creative spirits, especially filmmakers.