Magazine version in Acumen October 2016

Imagine you become obsessed with an obscure subject of study and spend fourteen years working on a book about it. In the course of your research you travel across East Asia, from Japan to Burma, by train and ship and bullock-cart. Then when the manuscript is finally complete you entrust your only copy to a friend who mislays it in a drunken stupor.

And that’s that. You never see the text again. For the year is 1948 and there are no such things as USB memory sticks or cloud storage.

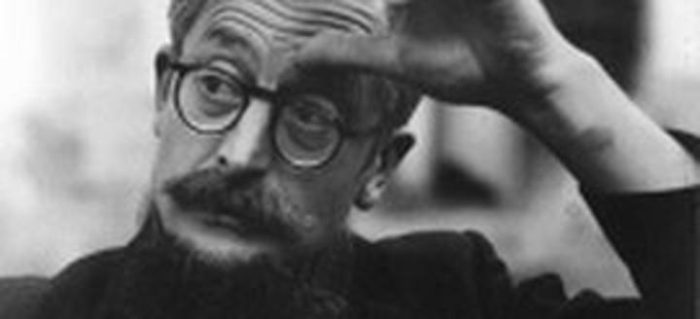

Such was the hand that fate dealt to William Empson, the celebrated literary scholar and modernist poet. Yet the story does have a happy ending – or at least a bitter-sweet one. Six decades later and long after Empson’s death in 1984, the manuscript miraculously came to light amongst a set of papers donated to the British Museum.

Now, in 2016, The Face of the Buddha has finally been published in a handsome edition that includes many of Empson’s own photographs, as well as plates of the artworks and images he had proposed to incorporate.

The introductory essay by Myanmar-based scholar and poet Rupert Arrowsmith is a tour de force of insights into Empson, Buddhist art and Buddhism itself.

You can buy the book here.

GROSS IMMORALITY

Empson was a man of extraordinary energy and talent. A mathematical prodigy, he turned his attention to literary criticism at Cambridge University and produced the ideas behind the ground-breaking Seven Types of Ambiguity while still an undergraduate.

In the late 1920s the academic study of literature was a new discipline and several of the major figures in the field – such as Empson’s mentor I.A. Richards and F.R. Leavis – would make their names at Cambridge. When Empson was awarded a fellowship, he seemed bound for a stellar academic career.

Fate intervened. A college employee found a packet of condoms in the twenty three year old’s rooms and it was also reported that a lady friend had stayed overnight. According to the puritanical ethos of the times, this was evidence of gross immorality. Not only was the brilliant young scholar dismissed from his position, but Empson’s name was permanently scrubbed from the college records and he was even banned from living in the town itself.

Empson spent the next few years preparing Seven Types for publication while free-lancing for literary magazines and drinking in the pubs of bohemian London with the likes of poet Dylan Thomas. In 1931 he secured a university job in Tokyo on the recommendation of Richards. He arrived just one month before the Manchurian Incident set Japan on a fifteen year path to war and eventual national destruction.

Like any 25 year old “fresh-off-the-boat” teacher with no knowledge of Japan’s language or social conventions, Empson had difficulty in integrating. As biographer John Haffenden relates, there was trouble on his very first night in Tokyo. After a drinking spree, Empson returned to his hotel after the doors had been locked. Undeterred, he clambered legs-first through a nearby window only to find himself in the staff room of the adjacent station, where he was seized by the startled railwaymen.

Once caught, it was not a burglar, but a university professor, was the embarrassing headline in the next day’s Asahi.

Empson’s first house was in Kojimachi, near the British Embassy. This allowed him to associate with the great Japanologist Sir George Sansom, who held the post of Commercial Counsellor. After a year Empson moved to Takanawa, from where he commuted to his teaching gigs by motorbike.

Empson also acquired a girlfriend, Haru (family name unknown). His relationship with her is the subject of the fine poem Aubade.

Hours before dawn we were woken by the quake.

My house was on a cliff. The thing could take

Bookloads off shelves, break bottles in a row.

Then the long pause and then the bigger shake.

It seemed the best thing to be up and go.

From Aubade, by William Empson

Empson disliked the increasingly tense political and social atmosphere and developed an aversion to the ambient cacophony of the city. The horn of the tofu-seller is the most melancholy sound I have ever heard, he told a student. He never learnt enough Japanese even to go shopping and, sadly, was not immune to the condescension and cultural prejudice typical of the period.

“THE FOOL WHO KNOWS”

Although out of sympathy with many aspects of contemporary Japan, Empson had a reverence for traditional Japanese arts. He had read Waley’s translation of The Tale of Genji while at Cambridge and soon developed an affinity for Noh drama, which he considered a greater art-form than Western ballet. As Haffenden writes, “the Noh, he believed, chimed with the philosophical ‘notion’ informing much of his own poetry – that ‘life involves maintaining oneself between contradictions.’”

His poetic output was affected too. Three poems appear In Empson’s 1940 collection The Gathering Storm – and subsequently in his Collected Poems – that are credited to “C. Hatakeyama (transl. W. Empson).”

For many years nothing was known about “C. Hatekayama” and there were doubts whether such a person even existed. In the late 1990s, however, poet and literary scholar Peter Robinson uncovered the history of Chiyoko Hatakeyama, an obscure but talented poet who was living in distant Aomori Prefecture at the time. Though they met only once, they corresponded for several years. Hatakeyama wanted to write original poetry in English, but instead her famous sensei took her English translations of her Japanese poems and reworked them for publication.

Describe the Fool who knows

All but his foes

Wading through tears striding the covered sneers

And against the tide, he goes

From The Fool by C. Hatakeyama (trans. W. Empson)

FEARFUL ASYMMETRY

Much of Empson‘s spare time was spent visiting temples in Tokyo and Kamakura, where he took painting lessons from the British wife of Junzaburo Nishiwaki, one of Japan’s leading poets of the twentieth century. The Buddhas, he declared to a friend, are the only accessible Art I find myself able to care about.

It was on a jaunt to the ancient capital of Nara in the spring of 1932 that he experienced the epiphany that led to the writing of The Face of the Buddha.When he viewed the seventh century wooden statue known as the Kudara Kannon at the Horyu-ji temple and the Miroku Bosatsu at the neighbouring Chugu-ji nunnery, he was immediately struck by the profound beauty of the statues.

Furthermore there was a feature, unremarked in any of the scholarly literature, that leapt out at him. The faces of the statues appeared to be asymmetrical, reflecting two different mental states. The right side (as we look), with its flat eye and mouth, conveyed “divinity”; whereas on the left side the eyes and mouth slanted upwards, conveying force and charm.

Empson was to find similar asymmetry in other early Buddhist statuary, in Japan and elsewhere in Asia. Being knowledgeable about contemporary science, he sought to relate his discovery to emerging theories of left brain / right brain functions. He also located facial asymmetry in photographs of Winston Churchill and other celebrities of the era.

Some of the most interesting illustrations in The Face of the Buddha are Empson’s own manipulated images of the statues’ faces. By doubling the left side and doubling the right side of a face, he gets drastically different expressions. His nude painting of Haru under blossoming cherry trees also displays marked facial asymmetry; passivity on the right side, powerful emotion on the left.

Empson’s manipulated photograph. From l to r, – original image, right side doubled, left side doubled.

SEXUAL TYPES OF AMBIGUITY

The man who revealed different layers of meaning in the poetry of Shakespeare and Donne had identified the same principle at work in the Buddhist statuary of the seventh and eighth centuries. Ambiguity, contradictions and complexity were the leitmotif of his work and also his life. According to Haffenden, it was an episode of sexual ambiguity that led to his premature departure from Japan.

A life-long bisexual, Empson appears to have propositioned a taxi-driver, who reported him to the police. Even given his notoriously poor eyesight, the explanation he offered to a friend – Japanese men and women look so alike I made a mistake – seems a stretch.

The older Empson went on to greater things – further renown as an academic and literary critic, a knighthood and, finally, full rehabilitation at Cambridge University, where his college awarded him an honorary fellowship. He never set foot in Japan again, but the influence of his Asian experiences was profound. He prefaced his Collected Poems with an extract from his own translation of The Fire Sermon, a Buddhist text. It was also read out at his funeral in 1984.