Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 2/11/2014

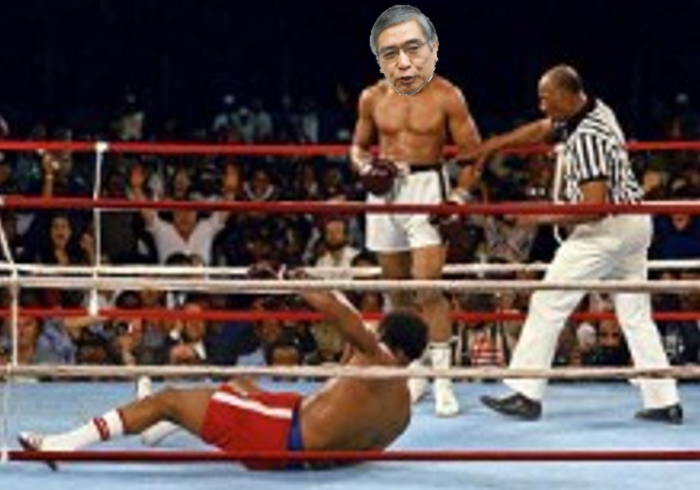

You have to wonder if Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda had been watching the fortieth anniversary reruns of the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the legendary heavyweight championship contest between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman.

Back then Ali, the underdog, startled the world with his “rope-a-dope” tactics. For round after round he stayed on the ropes, sucking up Foreman’s blows. Then when his opponent tired, he danced free and landed the devastating combination that won back his title.

Almost exactly forty years later Mr. Kuroda has won back his credibility with his market-jolting announcement of a second shot of “Quantitative and Qualitative Easing,” the radical reflationary policy that is at the heart of Abenomics.

The Kuroda version of rope-a-dope was expertly performed. For several months as the economic gloom thickened and Abenomics took a battering from critics of all stripes, he did precisely nothing. Indeed, he encouraged low expectations through a series of Polyanna-ish statements about how well things were going. On the eve of the Bank of Japan’s October meeting, only three economists out of thirty two expected anything new. It was then that Mr. Kuroda came off the ropes and delivered his knock-out blow.

Bluffology of this standard is rarely associated with Japanese officials. Almost as remarkable was the committee’s 5-4 vote to approve the new measures. In April 2013 when the first shot of QQE was administered, the vote was unanimous. Now Mr. Kuroda’s policies face internal as well as external opposition, but instead of stitching together some mealy-mouthed compromise, the usual bureaucratic tendency in such circumstances, he stuck to his guns. Next summer there will be a new appointment to the MPC and presumably the reflationists will see their numbers bolstered.

It has taken America’s Federal Reserve Bank almost six years to wind down its own programme of quantitative easing, so it’s no surprise that Japan requires another dose after eighteen months. After all in Japan’s case it wasn’t a question of merely quelling the fear of deflation, but of exorcising fifteen years of actual deflationary experience. Even so, disquiet and scepticism are widespread, as the closeness of the vote shows. Quantitative easing programmes have been controversial wherever they have been implemented, but there are at least two reasons why the pushback in Japan should be less fierce.

First, the claim that quantitative easing benefits only “bankers” and the rich is unlikely to gain much traction. In terms of the distribution of assets, Japan is a highly egalitarian society. According to a recent study by Credit Suisse Research Institute, the proportion of total wealth held by the top 10% was the second lowest in the 46 countries analysed. The 2014 Billionaire Census compiled by Wealth X and UBS indicates that there are more billionaires in Istanbul than there are in the whole of Japan. As for the Japanese banks, their profit margins are wafer-thin by global standards and the CEO of the largest earns about a twentieth of what JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon pulls down.

So who benefits when the value of the Japanese stock market rises? About a quarter of the market is owned directly or indirectly by individual investors, a third by foreigners and the remainder belongs to the system itself, via the web of holdings that link financial intermediaries and companies. In other words, corporate and financial Japan gets an instant boost to its equity base which, if sustained, will increase business confidence and the propensity to hire and invest and, eventually, to pay higher wages and bonuses.

That’s doesn’t mean that the stock market is irrelevant to ordinary citizens. In Japan there is a good correlation between stock prices and real estate prices and the home ownership ratio exceeds 60%. Waseda University’s index of house prices for metropolitan Tokyo is up 7% over the past 12 months and doubtless there is more to come. When the asset markets are rising, household wealth increases too.

The other knock against QE is that it creates financial bubbles that must inevitably pop, causing serious economic damage. Again, such fears are wide of the mark in the Japanese case. Even after the recent rises, neither real estate nor stock market indices are any higher now than twenty eight years ago. According to The Economist’s regular survey of house prices, Japanese residential property is the best value in the OECD. As for stocks, in terms of prospective PER (price earnings ratio) the Topix Index is at its cheapest since Ali decked Foreman on a sticky October night in Zaire.

Instead of trying to pump up already elevated asset prices, Mr. Kuroda is trying to break a pernicious feedback loop between asset deflation and economic weakness that has been in place for a generation. To change the national mindset he needed to be bold and unpredictable – and he was. His monetary version of the famous “Ali shuffle” provoked an instant market response: a vertiginous rise in stocks and precipitous slide in the yen, which must have been highly gratifying. Now Japan needs creative fiscal policy and institutional reforms to hammer the message home.