Fumi Suzuki, born 1898 – My mother once told me that I only just avoided being killed the day I was born. “Thinning out” babies was pretty common in the old days. It was thought bad luck to have twins, for example, so you got rid of one before the neighbours found out. Deformed babies were also bumped off. And if you wanted a boy but the newborn was a girl, you’d make it “a day visitor” as they used to say.

In my case I wasn’t deformed. I was downright ugly. My parents and grandparents were very shocked, apparently. “We’ll never be able to find her a husband – not with those looks,” they said. My mother told me that when she first saw my face, she thought, “What a waste of time, giving birth to a thing like that.”

This comes from Junichi Saga’s Memories of Silk and Straw – A Self-Portrait of Small-Town Japan, first published in English in 1983 and now available on Kindle. The remarkably vivid illustrations are by Saga’s father, Susumu, who wished to preserve a visual record of the town he had known in his youth.

Garry Evans’ translation is superbly natural and doubly impressive given that all the narrative voices speak in the local dialect.

You can buy the book here.

Junichi Saga is a medical doctor and writer who has reconstructed the bygone world of an early twentieth century Japanese country town by recording conversations with his elderly patients. His best-known work is Confessions of a Yakuza, published eight years after Memories of Silk and Straw.

That book gained worldwide attention in 2003 when it became clear that Bob Dylan had “borrowed” some fragments of its text for use in four or five songs on his aptly titled Love and Theft album. Dr. Saga handled the consequent brouhaha with grace and good humour. “I am very happy and very flattered,” he said. “His lines flow from one image to the next and don’t always make sense. But they have a great atmosphere.”

More from Fumi Suzuki – Killing off a newborn baby was a simple enough business. You just moistened a piece of paper with spittle and put it over the baby’s nose and mouth; in no time at all it would stop breathing. In my case the midwife wrapped me tightly in rags as well. Everyone felt relieved to have got the problem out of the way, and went and sat around the fire chatting over a cup of green tea.

Mother was asleep on her mattress. She told me that she woke up after a while and saw the bundle of rags moving. She could hear the baby crying. It really a gave her a start, she said.

The ruffian whose first person reminiscences are featured in Confessions of a Yakuza, is also one of the fifty-odd narrative voices who make up Memories of Silk and Straw. Amongst the other patients of Dr. Saga who offer up their experiences are two geisha women, a midwife, a horsemeat butcher, a tofu maker, a rice-cracker maker and numerous exponents of trades that have long since disappeared, such as blacksmith, executioner, rickshaw operator, reed thatcher, charcoal burner and various kinds of boatmen.

The past is another country and in this case one characterized by hardship and poverty barely imaginable a century later. This was a world where, in the words of the midwife, “working people spent most of their lives half-starved.”

As we learn from the lived experience of the narrators, male children of eight years old tilled the fields from four in the morning and female children of the same age were packed off into service; infanticide and the sale of daughters into prostitution were necessary evils; the poorer peasants wore the same clothes day and night, 365 days a year; people with infectious diseases were forced out of their villages and left to wander the countryside; outcasts roamed the mountains, living off wild dogs for food.

Despite –or perhaps because of – the harshnesss of the struggle for existence, people were adept in finding interludes of comfort and joy. In Dr. Saga’s own words, at festival time “the whole town, young and old, would pour out onto the streets in a happy throng…” On such special occasions there would be fish to eat and farmers would drink “terrifying amounts” of sake. A powerful communal spirit fostered resilience and solidarity in the face of adversity

Hiroshi Hisamatsu, born 1906 – I can’t complain. I may have been brought up in poverty, but there were a lot of happy times too.

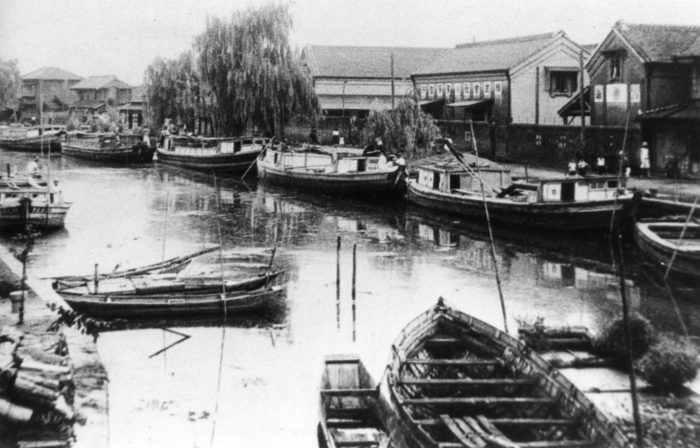

Today Dr. Saga’s home ground, Tsuchiura, is an unremarkable city of 110,000 people about an hour by train from Tokyo. In the early twentieth century, it was even smaller, with a population of 20,000, and it took the carter from dawn until late at night to make the round-trip. Heavy freight was transported by flat-bottomed boat down the River Tone and the journey could take over a week, depending on the weather.

Small and relatively unsophisticated as Tsuchiura was, it contained quite a complex economy, as the list of different trades suggests. For example the production of katsuo bushi (dried bonito for shaving into flakes) required a whole team of people to handle the various processes, with at least 24 men involved in the final “planing” of the block of fish.

There was a substantial red-light district too, which grew after the establishment of a naval air squadron base in the 1920s. At the peak there were seventy or eighty brothels, each staffed by between three and eight girls. There were also inns where the maids doubled as low-class prostitutes.

The geisha quarter was separate, both by location and by the class of the customers, who were officers and well-to-do merchants. As an ex-geisha patient of Dr. Saga notes, “the narrow road dividing the geisha quarters from the red-light district sometimes seemed almost to separate heaven from hell.”

One of her customers, who seemed unusually preoccupied one evening, took part in the assassination of Japan’s prime minister the very next day. Another helped to plan the attack on Pearl Harbour. Towards the end of the war, young pilots destined for kamikaze missions would come to spend their last night at training school with a geisha. “A lot of the girls were young too at that time,” the ex-geisha explains, “and just for a night they became young wives to comfort them.”

Back to Fumi Suzuki, who was such an ugly baby that her mother wanted her smothered at birth – When they unwound the rags they saw that the baby was still alive. It began bawling its head off. “What the hell do we do now?” they all thought; they eventually decided that the kid must have been fated to survive and that to try and kill it again would bring bad luck on the house. So they let me live.

Luck’s a funny thing, you know, and as it happened, I managed to find a man, married him at the age of twenty and came to live in Tsuchiura.