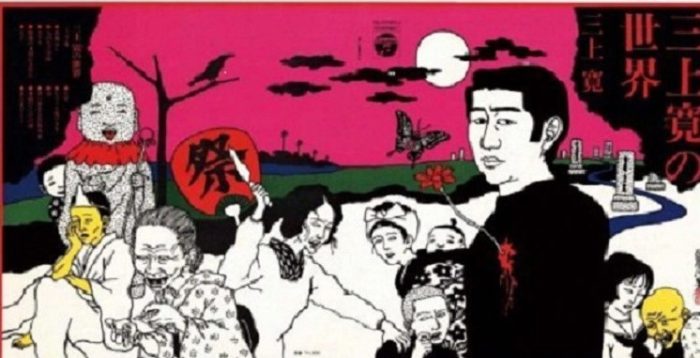

It was in the early 1970s that Kan Mikami exploded like a hand-grenade onto the Japanese music scene. Remarkably he is still at the top of his game today, delivering intense shamanic performances on a regular basis.

You can check his schedule here.

Like his acquaintance Shuji Terayama, Mikami is a native of Aomori Prefecture with a thick accent to prove it. In his early years he sounded like a combination of Tom Waits and John Lee Hooker.

At the time the Japanese folk scene was dominated by mild-mannered figures such as Takuro Yoshida with conventional “good” voices. Apparently at joint concerts some of their female fans would escape to the toilet when Mikami started performing.

Clearly, though, as the clip above demonstrates, he got a tremendous response from fans who understood what he was doing. The original version of Night Opens My Dreams was a woman’s statement of hope in the face of adversity. Mikami turns it into a howl of despair, keeping only the title phrase from the original.

Mikami’s lyrics are nihilistic, surreal and packed with taboo-busting words and imagery. Regular themes include death, violence, rape, poverty, masturbation and madness. There’s also more than a tinge of Buddhist philosophy behind all the transgression.

A one-eyed red dragonfly comes flying

My balls are sometimes lyrical

At the bottom of the swamp

Shepherd’s purse* hungers for meat

Life is a game rigged by god

It’s a lucky draw with a deadly viper

The sewer is the path to hope

From Echo, Electric Pot

*A weed believed to be carnivorous

Mikami has published several books of poetry and runs a school for poets. He is also an accomplished actor with credits in Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno movies and the legendary gangster series Battles without Honour and Humanity, as well as mainstream offerings like Nagisa Oshima‘s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

His first screen role was a one minute cameo in Shuji Terayama’s To Die in the Countryside (1974), in which he appears in the background and interrupts a conversation between the young Shuji and the adult Shuji.

Just as Terayama considered regional dialects to be more authentic than standard Japanese, Mikami sees the countryside as a deeper reality which provides a critique of the superficiality of urban living. In a recent interview he commented as follows –

Music is originally a kind of crop. It needs earth to thrive, just like radishes… The best example of that is voice quality. My voice is the voice of the countryside… There are no crops in the city, just the culture of consumption, so no music can be born there…

And echoing the title of Terayama‘s autobiographical movie:

There is death in the countryside too. Somebody once said that modern society seeks to distance itself from death, but the countryside means death. Fathers die, mothers die, brothers and sisters die. Death in that sense doesn’t exist in the city…

The Warrior’s Rest was originally a poem that boxing fan Terayama wrote for the great Japanese world champion Fighting Harada. The title comes from a French film, Le Repos du Guerrier (known in English as Love on a Pillow) starring Brigitte Bardot.

Kan Mikami was born in the Tsugaru region, on the remote northern coast of Aomori Prefecture. After leaving school he spent some time at the local police academy before joining the “runaway movement” inspired by Terayama and moving to Tokyo. Having lost his father at a young age, he sent half the wages he earned as a chef and from odd jobs in the Golden Gai bar district back home to support his mother and younger sister.

All the while he was developing his unique musical style. Mikami’s first album was withdrawn from sale after complaints about the sympathetic portrayal of a young killer, who happened to be the same age and from the same hometown as himself, in a song called Pistol Devil Boy.

Mikami established his reputation with his blazing performance at the 1971 Folk Jamboree (see first clip). He has subsequently worked with samisen players, jazz musicians and “noise artists” such as Keiji Haino, as well as more conventional singers.

From an interview with Shuji Terayama

Q. What do you want most of all?

A. What do I want? Well, a lot of things, I suppose. They’re things that are inside myself. Still, I’d like to have a thoroughbred horse.

From an interview with Kan Mikami

Q. What do you want most of all?

A. I want the living Shuji Terayama.