Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 13/6/2017

Could Japan’s supposedly “disastrous demographics” be a blessing in disguise?

With Japan’s traditional labour force of 15 to 65-year olds declining at around 1% per year, Japanese managers are confronting a phenomenon few will have experienced in their careers – a structural labour shortage. Corporate behaviour is already changing and will need to change much further.

Kansai Electric Power, music label Avex and parcel delivery giant Yamato Holdings are among major Japanese companies called out publicly in recent months for not making proper overtime payments to their over-stretched, underpaid workers.

Yamato’s solution has been threefold. It has raised the price of its delivery service for the first time in 27 years in order to cover higher wages. It has introduced a four-day week with longer shifts. And it has set up an experimental venture with e-commerce provider DeNa to develop a new kind of delivery system. By applying its ubiquitous “black cat” brand to self-driving “Robo-cat” vehicles, Yamato hopes to create ”proxy shopping” and on-demand, “anywhere anytime” services.

Regardless of whether the rise of the robocats actually happens, companies will have to be much smarter in their use of human resources. The Abe administration is promoting “hatarakikata kaikaku”, “reform of working practices”, in reaction to some high profile deaths from overwork and a general perception that long working hours and excessive reliance on overtime are inefficient and a barrier to working women. Ultimately the shortage of labour will enforce through necessity what the government is seeking to achieve through persuasion.

As the balance of power shifts from employer to employee, expect to see Japan’s relatively undeveloped labour market become much more active with job turnover reaching new levels. In order to hold onto staff, companies will have to offer child-care facilities, subsidized gym memberships and other perks – altogether, a better work-life balance.

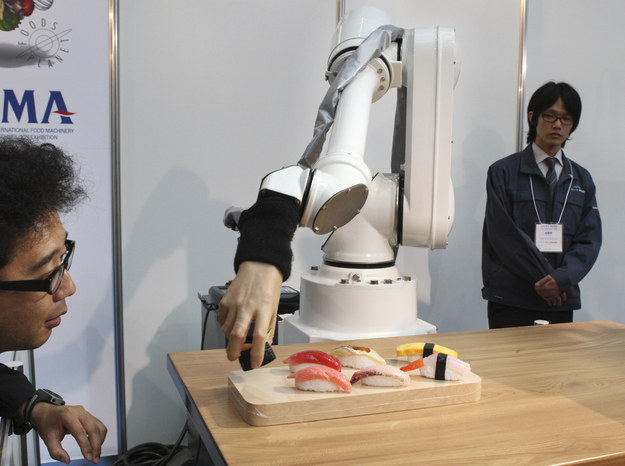

There will be more investment in automation, particularly in the service sector, and a wave of mergers and takeovers in labour-intensive industries as margins are eroded by rising real wages. Plenty of gains can be reaped from, for example, Japan’s heavily overstaffed retail banking networks. Internet and phone banking have barely got off the ground and queuing and paper-shuffling are still the order of the day in most bank branches

Increasing numbers of mainly Asian foreign workers are already visible in Japan’s convenience stores, restaurants and building sites. This trend is likely to accelerate as bottlenecks grow more severe.

However, mass immigration was never on the cards in Japan, even before the upsurge in terrorism in Europe and elsewhere gave such a graphic demonstration of the risks involved. Instead, Japan is likely to expand and extend the visa programs by which foreign workers learn Japanese and work for several years before returning home. This East Asian version of Germany’s old “gastarbeiter” system can deliver a win-win for both sides of the transaction.

HARVESTING THE GREEN RICE

The last time Japan saw a true sellers’ market for labour was in the late 1980s when the economy was frothing away like a malfunctioning cappuccino machine. In order to secure graduates from the top universities, blue chip companies engaged in the practice of “aotagari” (literally, “harvesting the green rice”) by signing them up well before they had finished their studies. In some cases, cruises and overseas trips and were included in the recruitment process.

When boom turned to bust, Japanese companies found themselves with an excess of staff, to go with the excess borrowings and excess capacity they had accumulated. The bubble in personnel duly burst. The jobs-to-applicants ratio, a standard measure of labor market tightness, fell as hard as the Nikkei Index of stock prices.

The post-2009 improvement in the ratio has already outstripped and outlasted the unsustainable surge of that era. Since far more women work now than 25 years ago, the proportion of the 15-65 year old population actually in employment is at record highs The dynamic is very different too. This time companies have been cautious recruiters, favouring part-timers, with their lower wages and minimal social overheads, over full-time workers.

THE PENDULUM SWINGS

Yet the supply of new part-time workers – mainly women and retirees – is not inexhaustible. Female labour force participation in Japan is already above the G7 average and participation by the over 65s is double that in the UK and almost four times the German proportion. Meanwhile, the Abe administration has launched an array of measures designed to promote the hiring of full-timers over part-timers. With growth in full-time employment at its strongest since the early 1990s, there are clear signs that the pendulum is swinging back to job quality.

In such circumstances, you would expect to see wages rising. No signs are visible in the official numbers, largely due to the jump in participation and the arithmetical effect on average wages of an increasing number of lower-paid part-timers. Yet data collected by placement company Recruit indicates that part-timers themselves are seeing wages rising at an annualized 2.6%, the highest rate on record and a solid gain in real terms.

Unless policy-makers tank the economy through ill-considered tightening measures, the likelihood is that labour shortages will spread and wages pressures will increase. Given that services make up 40% of the consumer price index, this should confirm Japan’s long-awaited exit from deflation.

According to the OECD, Japan’s productivity per hour worked is some 25% below the G7 average and only just tops the levels of Trinidad and Tobago, When resources are abundant, the result is often waste. When they are scarce, the result is efficiency. For decades, a plentiful supply of diligent, obedient workers has been taken for granted by Japanese managements. No longer.