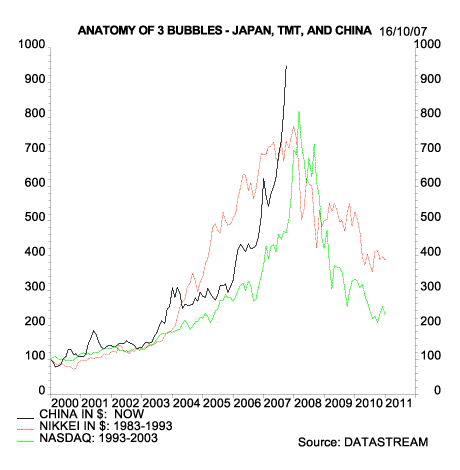

The performance of the Chinese market now comfortably exceeds that of other classic bubble markets – Japan in the late 1980s and TMT in the late 1990s. Bubble markets have much in common, including the inevitable denouement.

A Chinese coal mining company now has a market capitalization larger than Toyota. A Chinese bank is 50% larger than that Citicorp. The Shanghai market trades on a PER of 50X and PBR of 7X. The rise in Chinese market cap this year is equivalent to the total value of the French CAC.

Haven’t we seen this movie before? Yes, we have. In fact some of us have seen it twice. Let’s go through some of the similarities and differences, using Hyman Minsky’s famous 7 stage model.

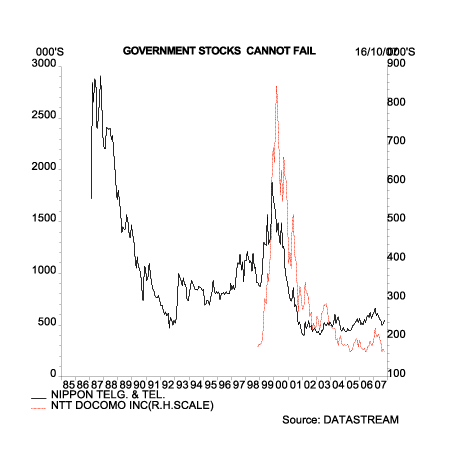

Government stocks can not fail

1. Displacement. Most investors are mostly sane most of the time. It takes a “displacement” (ie. a large-scale disturbance in prevailing assumptions) to generate the disorientation necessary for a mania. The seemingly unstoppable rise of Japan in the 1980s was a geopolitical example, as is the emergence of China as a world power today. The internet was a technological example.

The effect of a displacement is to convince investors that “it’s different this time”; that previous rules no longer apply; that history has changed course and you need to be on the right side of it. And in fact there is always some validity in the claim. Cheap new communication/transportation technologies only emerge a few times a century, likewise the catapulting of a third world economy into the ranks of economic superpowers. Nonetheless, the fundamental drivers of investment return remain unchanged.

Displacements may generate super-charged growth, but they also generate super-charged competition. And though rare, they are not as unique as the hype makes out. The precedents for the Internet were the 19th century railway booms and the early 20th century auto and radio industries. The precedents for “the China macro story” are Japan in the 1950s and 1960s and Korea and Taiwan in the 1970s and 1980s – periods of astonishing growth in which, nonethless, stock market valuations remained very low.

2. Price increase. In the early stages, fear of the new dominates. Valuations are modest, and information is hard to come by. Only sophisticated investors are prepared to accept the risk. Japan in the early 1980s as still unknown territory. The second section company handbook was not even translated into English. Likewise, the mid-90s internet was the preserve of geeks and venture cap specialists, its potential dismissed by even such figures as Bill Gates and Rupert Murdoch. Likewise Chinese stocks lagged the early stage of the post-2003 bull run as investors worried about “poor corporate governance,” “dodgy accounting”, and “NPLs equivalent to 15% of GDP.” Needless to say, nobody worries about these issues now, though we suspect the reality has not changed very much.

3. Easy credit/irresponsible monetary policy. Liquidity is the fuel that enables manias to blaze stronger and longer than anyone expects. The BoJ in the 1980s and the Greenspan Fed of the late 1990s have been criticized for failing to tighten in the face of rip-roaring asset inflation. However those oversights are small beer in comparison to current Chinese policy, which requires deeply negative real interest rates in order to hit a desired forex target. The result is a current account surplus which, as a percentage of GNP, its twice what Japan’s was at the height of the trade friction. At the same time financial liberalization has opening the securities markets, offering a simple alternative to value-losing bank deposits. It is hard to imagine a configuration more likely to generate a monster boom-and-bust cycle, in financial assets and the real economy. Financial liberalization and currency manipulation were of course key factors in Japan’s 1980s mishaps.

4. Over-trading. Minsky’s fourth stage is what happens when trading volumes explode as investors rush to take advantage of accelerating price momentum. In the TMT bubble, the sudden emergence of a day-trader culture brought large numbers of inexperienced investors to the party, and “new breed” analysts and fund managers became prominent even in traditional institutions. In late 1980s Japan, corporations became huge speculators via “zaitech” punting funds. All these phenomena are visible in today’s China . Indeed as the country’s stock market culture is so young, there will be next to nobody who has learnt the value of fundamentals the ahrd way.

5. Euphoria is when the party starts to get truly wild and crazy. Bearish commentators are now discredited and silenced as the doom they predicted fails to materialize. More and more securities companies set up shop, and the salaries of salesmen and analysts – some of them fresh off the boat – heads for the stratosphere. Meanwhile the new breed of “no fear” fund managers rules the roost, and new valuations measures are created to justify the new levels of stock prices. The TMT bubble produced eyeballs and clicks /per share. 1980s Japan came up with a variation of Tobin’s Q ratio which implied that, since companies cross-held each others’ shares, higher stock prices raised the value of corporate balance sheets and thus justified almost any conceivable market level. We have yet to see anything as creative out of China, though we have learnt that a small free float for a stock ensures “positive supply and demand, and “ an unprecedented macro story justifies unprecedented valuations.”

Such is the bullishness that IPOs routinely open at massive premiums. Is it credible that the underwriters are underpricing them grossly and repeatedly? Nobody stops to think. The letters “IPO” are themselves a magic incantation. The classic example in the Japanese bubble was NTT (9432), which was 6X oversubscribed when it was offered to the public at 1,197,000 per share in 1987. Within a month . the price hit 3,000,000. Twenty years later, it trades well below half the original IPO price. But at least it still exists, which is more than be said for some of the hottest IPOs of the TMT bubble!

Government stocks can not fail

The NTT and NTT Docomo IPOs also benefited from a strange quirk in the euphoric mindset – the belief that the authorities are almighty and will somehow contrive to prevent unfortunate outcomes. Thus government-sponsored IPOs were believed to be particularly exciting since they would “not be allowed to fail.” A strong form of this mindset, prevalent in 1989/90 , held that “the ministry of finance will not allow real estate prices to fall since the consequences would be devastating.” Sadly, only one half of that statement proved to be correct.

The equivalent in today’s China would be the belief that nothing bad can happen “until after the Beijing Olympics.” This despite the fact that the Chinese authorities evidently have little control over vast swathes of their economy and financial system.

As euphoria reaches its peak, the opportunity costs of sensible investing become too high for many professionals, who are under competitive pressure to perform. In 1999, that led to cheap good quality “old economy” stocks slumping, while money poured into the “new economy” names with the strongest momentum. For “old economy” and “new economy” in 1999, you can read “Japan” and “China” in 2007. That giant sucking sound you hear is capital being syphoned away from cheap, dull Japanese stocks and pumped into the “Greater China” theme.

6. Insider Profit Taking. The remarkable thing is that despite the overwhelmingly bright prospects, some well-informed people are sellers of large amounts of stock. Corporations race to launch IPOs and secondary offerings. They never buy their own stock from the market. Thus the go-go Japanese warrant market of the late 1980s, soon to disappear with the bull market that spawned it. Managements use their high valuations to acquire other assets, thus exporting the bubble to other asset classes. The “Japanese wall of money” that hit LA real estate in the late 1980s has its equivalent in the “qualified investor” influx into Hong Kong today.

7. Revulsion. This is the endgame, when the bubble psychology is finally destroyed. It can take the form of a sudden plunge, as with the Nikkei in 1990 or, more usually, a complex top , as with the Nasdaq in 2000. Optimism sours, though the bulls keep up the happy talk as the market “slides down the slope of hope.” The process is not complete until valuations have returned to their starting point. In 2007, Japanese PERs and PBRs are lower that they have been for a quarter of a century. The current PER on Nasdaq is also low by historical standards. In the case of China, an equivalent “round-trip” would return the market PER to 12-15X.

In the revulsion phase, the authorities often claim that while “a healthy correction” is occurring in asset prices, strong fundamentals ensure that the real economy will not be damaged. This was more or less consensus in early 1990s Japan, and confidence in “a soft-landing” was widespread. Unfortunately major financial bubbles are always accompanied by real economy bubbles, usually manifested in excessive capital spending. The purging process involves a recession or – in the case of Japan – a series of recessions.

In the aftermath of a world-class bubble, the psychological trauma is so intense that the entire asset class remains discredited until a new generation of investors appears on the scene. In popular perceptions, the phrase “dotcom stock” is indelibly associated with worthlessness, hype, and gullibility. When questioned, investors are embarrassed to have been associated with the whole topic, and usually claim to have been “out well before the top.” The same goes for Japanese real estate and bank stocks; the ones that survived took fourteen years to bottom out. We have little doubt that a similar reaction will be produced this time.

Bubbles are best analyzed in hindsight, and there can be no definite assessment as to what stage of the process China has reached. But judging from the limited and mostly anecdotal evidence that comes our way , we would suggest it is much closer the end than the beginning.