Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 13/7/2019

John Hiromu Kitagawa, founder of Johnny & Associates — better known as “Johnny’s” talent agency — was an extraordinary character who grabbed an opportunity that could only have arisen in Japan’s post-war upheaval and ran with it all the way, creating some of the top “boy bands” of the past four decades.

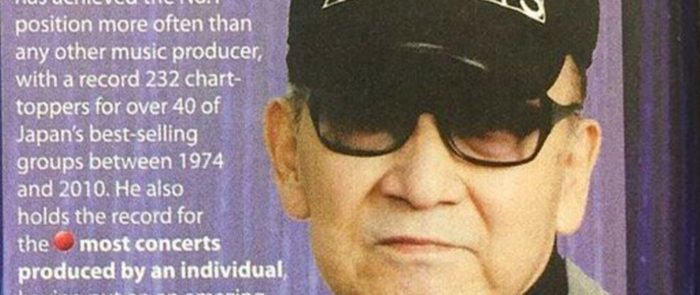

Kitagawa, who died in Tokyo on July 10 at the age of 87, made an indelible mark on Japanese society and popular culture well beyond Japanese shores.

For better or for worse, J-Pop would not be what it is today without the innovations that Kitagawa pioneered. These had nothing to do with music and everything to do with the system he created, which gave him total control over the personal lives and careers of his stars and formidable influence over the Japanese media, by feeding its hunger for obedient, unthreatening celebrities.

His power over the industry was so great that he survived even a court ruling – which he had contested – that he had sexually exploited some of his underage employees.

Kitagawa did not create the idea of the boy band, but he was one of the first Svengali figures to realize that it was possible to manufacture them from scratch, with musical talent not just unnecessary but probably a hindrance.

Inspired by seeing the American musical “West Side Story,” he wanted his roster of (exclusively male) talent to be able to dance and act too. What he was manufacturing was the generic celebrity, a boy-man who could appear on quiz shows, open supermarkets, pitch products in television commercials and act in movies.

If rock stars, with their unconstrained egos and hedonistic excesses, represented the extreme of Western individualism, Johnny’s entertainers were “anti-rock stars,” representing the selfless devotion to the organization of Japan’s “sarariman” (salaryman) society of the era. Indeed, like employees of major companies, they were expected to live in a dormitory — in some cases from a very early age – with key details of their lives, including romantic liaisons, carefully mapped out.

He launched The Four Leaves in 1967, but the real heyday of the Kitagawa operation came in the 1980s and 1990s, when you could hardly switch on a television set without coming across one of “Johnny’s” talents, singing, laughing or selling.

TV was intrinsic to his success. Fans consumed his product not by listening to songs on the radio — he actively dissuaded his stars from releasing CDs, which he considered a distraction from their real jobs — but by watching prime-time TV variety shows and enormous, circus-like live events. Looking good, in a boy-next-door sort of way, was much more important than sounding good.

Only a few, highly successful Johnny’s stars, such as Takuya Kimura, or “Kimutaku,” once of the celebrated boy band SMAP and now an in-demand actor, have had the confidence to strike out on their own. Most have stayed on the roster, knowing that crossing Japan’s premier impresario would probably lead to career doom.

According to gonzo writer Hunter S. Thompson, the music industry is “a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs.” It is also hypocritical. Early this year, for example, when Pierre Taki, a Japanese actor and half of the synth duo Denki Groove, was arrested for cocaine possession, his record company rushed to stop all distribution, physical and digital, of his work, which is now unobtainable.

Kitagawa survived scandals that many would consider far worse. He was never charged with any crime, but in the course of a libel battle in the early 2000s, the Japanese courts confirmed that Kitagawa had engaged in sexual exploitation of his young male talent in the dormitories and elsewhere. His power in the industry silenced would-be accusers and the mainstream media was loath to take him on.

In the 1970s and 1980s, there seemed to be a huge cultural gap between the J-poppers, boy bands included, who dominated the Japanese scene, and the supposedly more “authentic” Western stars. That was always an exaggeration. Manufactured stars — like Billy Fury and Adam Faith in Britain and Bobby Vee and Fabian in America — were nothing new.

Now, of course, boy bands are everywhere, though the definition is vague. In a 2012 poll of readers of Rolling Stone magazine, The Beatles were chosen as the second best boy band, while top place was taken by One Direction. In a world of manufactured talents such as Britney Spears and Justin Bieber, where former Disney child star Miley Cyrus plays Britain’s Glastonbury Festival, and where British impresario Simon Cowell — Kitagawa’s true successor — can make or break an act, authenticity is no longer a useful concept, if it ever was.

Kitagawa’s background was complex. His father was a Buddhist priest who had been sent to Los Angeles. The family moved to Japan on the eve of the Pacific War and young John spent the war years in Wakayama Prefecture, south of Osaka, before returning to the United States for high school and college.

Back in Japan again, he worked for the U.S. military as an interpreter and was dispatched to the Korean peninsula when war broke out there. Thanks to his talent for languages, he picked up Korean quickly.

Ironically, it is the stars of South Korean “K-Pop” who have truly globalized the boy band concept, while Japanese boy bands have failed to break out beyond their domestic market. Rather as South Korea’s Samsung Electronic has gone from strength to strength while Japan’s Sony and Panasonic have struggled to restructure their businesses, K-poppers have outshone their Japanese counterparts.

South Korean hit band BTS recently played London’s Wembley Stadium in front of 60,000 fans and topped the U.K. album charts with their “Persona” release, feats that no Japanese boy band could hope to emulate.

Though Kitagawa did not manufacture or manage BTS or any other K-pop band, BTS’s global following is probably the best tribute to his commercial foresight. Now somebody from a new generation needs to come up with a global vision and do for J-Pop what has already been done for anime and manga.