Published in Nikkei Asia 11/10/2021

“What will unfold might be inflation, a financial bubble and subsequent financial crisis, social discontent due to widening inequalities in wealth, a continuous decline in the growth rate or some combination of these factors… There is pressing need for change. I believe everything starts with recognizing clearly where we are and where we are destined to go unless we change course.”

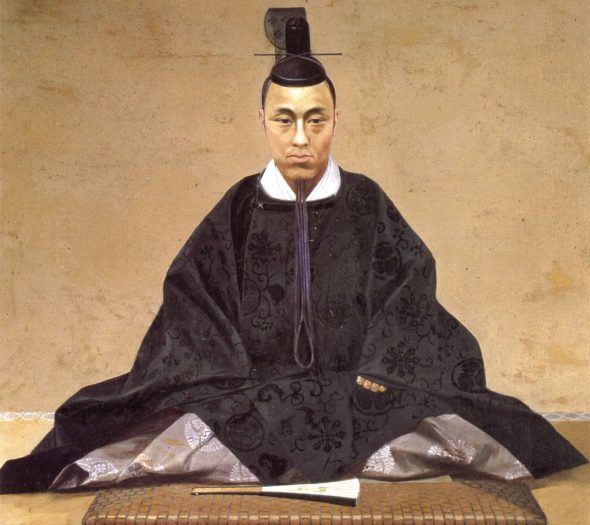

This is the doom-laden prophecy with which former Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa ends his newly published 530-page memoir Tumultuous Times, Central Banking in an Era of Crisis.

Although his criticisms of the super-low interest rate and quantitative easing policies deployed by central banks are diplomatically expressed and never personal, it is clear that he thinks we are all going to hell in a handbasket.

Not only is unconventional monetary policy failing to cure the developed world’s ills, in his view it is actively making them worse. Using the concept of hysteresis (persistence of a state), he suggests that unnaturally low interest rates prolong themselves as demand is sucked from the future and companies and projects proliferate that would be unviable at higher rates.

To understand where Shirakawa is coming from, it is necessary to understand Japan’s recent economic history. Just as American policymakers today are mindful of the lessons of the Great Depression and their German peers are guided by folk memories of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic, so Japanese financial officials are forever scarred by the experience of the disastrous bubble economy of the late 1980s.

The lesson learnt: You don’t need hyperinflation or mass unemployment to destroy a nation’s economic well-being. A large enough bubble will do the job just as effectively. And the Japanese bubble was one for the ages, comprehending real estate of all kinds, stocks, artworks, golf-club memberships, ornamental carp, anything that could be traded.

When it burst, the price of commercial real estate in Osaka, Japan’s second city, fell by 90%. The Nikkei Stock Average embarked on a 20-year bear market and has yet to recover its highs. Compared to this, other modern bubbles were as the popping of children’s balloons to the crash of the Hindenburg airship.

Shirakawa joined the BoJ in 1973 after studying economics at the University of Tokyo. The bank sent him to the University of Chicago, where he was taught by Nobel Prize-winner Robert Lucas and audited lectures by another Nobelist, Milton Friedman. Much later, Friedman was to criticize the Bank of Japan’s passivity in the face of deflation.

When the bubble madness was at its height, Shirakawa was a diligent, promising staffer in his late 30s. In his memoir, he attempts to deflect the blame from the institution where he spent most of his career. Indeed, as he points out, everyone bought in to the bubble logic — politicians, businessmen, intellectuals, the media, even foreign scholars and journalists who wrote best-selling books about how Japan was destined to unseat the U.S. as the world’s premier power.

Yet none of the above were charged with supervising Japan’s money supply and credit growth. That was the role of the BoJ, and it comprehensively failed in its mission.

The ensuing loss of faith in the authorities, including politicians and elite Ministry of Finance bureaucrats, was a bitter pill to swallow. The determination not to make the same mistake again became ingrained.

When official land prices finally bottomed out in 2006, the Bank of Japan stopped its quantitative easing program and raised interest rates, while the Financial Services Agency demanded more stringent lending standards. The “mini-bubble” that they were determined to stamp out consisted of a rise of 8% for residential plots in Tokyo, but of just 0.1% for the country as a whole. In many regions prices were still falling. The financial bureaucrats were jumping at shadows.

Shirakawa took over as BoJ Governor in early 2008 and experienced the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and Japan’s triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown in 2011. Whenever anything bad happened, whether overseas or domestically, the yen would strengthen, moving from 103 to the dollar to 76 in the course of his term.

A strong currency is appropriate if economic conditions are buoyant, but after the earthquake the Japanese economy was on its knees. Unsurprisingly, monetary policy became highly politicized, with businessmen, politicians and private sector economists increasingly vocal in their demands for a more reflationary policy.

Shirakawa held firm, maintaining that there was nothing he could do — the excessively strong yen was caused by overseas factors. He was and remains a strong advocate of fiscal tightening via tax hikes. Nowhere in his memoir does he address the point that Japan’s government debt is merely the other side of the balance sheet to the Mount Fuji of savings built up by Japanese companies and households.

Finally, the inevitable happened. Both public and politicians tired of hair shirt economics. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reappeared on the scene with a reflationary program that was to become known as Abenomics and give him a second, record-breaking stint in power.

Almost from the moment that Abe won the leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party, the yen fell sharply on the foreign exchange markets, as investors began to factor in a major change in policy settings. Shirakawa argues, very unconvincingly, that the rapid retreat of the yen to more than 100 to the dollar was caused by developments in the Eurozone crisis, not the imminent end of his own hardline policies.

Never say never, but so far the yen has not returned to anywhere near those nosebleed levels of the Shirakawa years.

Something similar happened in the stock market. In September 2012, just before Abe’s comeback, the Nikkei average was languishing at 8,870, the same level as in 1983. In a matter of weeks, it had embarked on a bull market that is still extant today, even after a trebling in price. Importantly, the rise has not been caused by bubble-type speculative excess, but by “fundamentals” — a remarkable improvement in Japanese corporate profits.

A man of principle, Shirakawa took the unusual step of resigning a few months before the end of his term, recognizing that he was not the right person to implement Abenomics after Abe’s landslide general election victory gave him a popular mandate.

Shirakawa published the Japanese version of his book in 2018, but has revised it and added new sections for the English version, which has comments on the COVID-19 era. He writes modestly and perceptively about the limited nature of our economic and other knowledge and makes some strong points.

Crucially, “unconventional monetary policy” has not succeeded — in Japan or anywhere else — in achieving its primary goal, which is to raise the rate of inflation. Is that because it has not been combined with expansionary fiscal policy, or is the structural force of shrinking demographics the key factor in staunching inflationary pressures, as Shirakawa believes? We will find out over next few years.

According to Shirakawa, the success or failure of monetary policy can only be judged in the long-term, by which he means in decades. On that basis, it is still too early to judge his record, but the same should go for his successor, Haruhiko Kuroda.

Japan appears to be in a much better place now than it was in the pre-Abe years, but Shirakawa’s views and analysis are of great interest, nonetheless. In fact, they probably have more applicability in the U.S. and the U.K. — where asset bubbles, inequality and inflation are clearly visible and could well have dire economic and social consequences.

If they do, Shirakawa will have been at least partially vindicated.