Published in the Mekong Review May 2018

A Tokyo Romance By Ian Buruma

Penguin Press 2018

The past, as they say, is a foreign country. Certainly, Japan in the 1970s was a very different place from Japan in 2018. I was there for the tail-end of the decade, a callow youth stuck in a non-airconditioned, four-and-a-half tatami mat* room in the badlands between south Osaka and fume-spewing Sakai City.

Unlike Ian Buruma, I did not rub shoulders with world-famous movie directors, charismatic female poets or highly cultivated gay expatriates in exile from their puritanical homelands. The other occupants of the dormitory were young Japanese salarymen who worked like demons but also drank, smoked and caroused like demons too.

I also was a beneficiary of white privilege. In recognition of my status as the sole foreigner in residence, every day I was provided with a “western” breakfast of a cold fried egg perched on a mini Mount Fuji of chopped raw cabbage.

We shared a communal bath that could hold five bodies and the doors were closed at midnight – a restriction easily circumvented by clambering through an upper floor window which was helpfully left open.

The airborne pollution was as bad as in today’s China; people burned their trash in the streets. Vacuum trucks would come and pump the sewage out of septic tanks, sometimes leaving behind a malodorous token of their work.

On hot summer nights, older men would stroll to the public bath in their longjohns and vests. On local trains with no air-conditioning, they would sometimes take off their trousers and fold them neatly in their laps. The neighbourhood café was frequented by bikers and surf-bunnies who extended my vocabulary considerably.

One friendly chap, who wore a Hawaiian shirt and aviator sunglasses, offered to take me drinking several times a week on the sole condition that I would speak English – needed, he explained, for the frequent business trips he was making to South East Asia. After the second drinking session, I was warned off by the dorm supervisor. My new pal turned out to be a mid-ranking officer of the area’s dominant yakuza syndicate.

The “Cool Japan” of Michelin-starred sushi shops and Pokemon Go interactive games lay far in the future. This Japan was warm, wet and chaotic. Like Buruma, I was instantly smitten. Like him, I was warned by friends that foreigners in Japan would always be “gaijin” – literally, “outside people” – no matter how long they stayed or how fluent they became in the language. Donald Richie, the late writer and film critic who became the young Buruma’s mentor, is quoted as follows:

“The great mistake was to think you could ever be treated in the same way as a Japanese. People would be polite, even warm. Profound friendships with Japanese were perfectly possible. But you would never become one of them.”

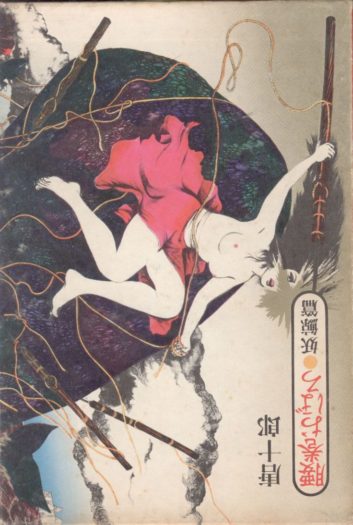

This suited Richie fine; he reinvented himself in Japan, lived most of his life there after arriving in 1947 and died there in 2013. It suited Buruma too, for a while at least. He became friendly with avant garde theatre director and actor Juro Kara and eventually joined his “Red Tent” troupe for a tour of Japan. After a series of disturbing and hilarious episodes, Buruma found the internal dynamics of the theatre troupe, which was every bit as hierarchical and exclusionary as a Japanese company, hard to take. After one bust-up, Kara dismissed him with the stinging words: “So you’re just an ordinary gaijin after all.”

Shortly afterwards, Buruma moved to Hong Kong, then London and later, the U.S., reinventing himself as a journalist, author of many highly-praised books, lecturer in human rights and, as of last year, editor of the New York Review of Books. Yet his six years in Japan changed him profoundly. As he writes, “even though I decided to leave Japan, I knew that Japan would never leave me.”

A Tokyo Romance is the story of a society and an individual, both in flux at a particular historical moment. It is also a non-fictional bildungsroman, a portrait of a young man struggling to understand himself and his place in the world.

The scion of a well-off Anglo-Dutch family, Buruma describes himself as a rebel against his privileged background with a strong dose of “nostalgie de la boue” – literally “a hankering after mud,” meaning a fascination with the seamy side of life. There was plenty of “mud” around in 1970s Japan.

A restless spirit and fascination with Japanese theatre and film landed him a scholarship to a Japanese film school. Buruma is sharply critical of his younger self, uncommitted, directionless, “hovering on the fringes.” It was the example of the uncompromising, driven figures of the avant garde art world he encountered in Japan – and the transgressive Kara in particular – that shook him out of his dilettantism and gave him purpose.

There’s a larger theme here too, one especially pertinent in today’s world of rapid globalization and the pushback against it. Buruma is by background and conviction a cosmopolitan. Japan is deeply insular, in absolute terms less now than in the 1970s, but relative to global trends probably more so. The cultural specificity of Japan which so attracted Buruma is the result of the protective insularity which keeps immigration to a trickle and ensures that a gaijin will always be a gaijin.

As a public intellectual of impeccably liberal inclinations, Buruma deplores nativism and nationalism and supports the intermingling of people and cultures. Yet it is the “Otherness” of Japan that enchants him in a way that is more erotic than romantic; he yearns “to plumb its mysteries, not just mentally, but physically.” And indeed in the 1970s he set out to do just that, with numerous women and a few men.

Many years ago, Buruma published a fine book of essays called The Missionary and the Libertine. The title refers to two contrasting tendencies in western attitudes to Japan and other Asian countries. The missionary wants to reform the natives, to make then more like us. The libertine luxuriates in the difference.

Buruma himself is a fascinating mixture of the two. Professionally and intellectually, he is a missionary. Indeed, he was one of the five hundred mainly American and British academics who signed a letter in 2015 “rebuking” Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for holding politically incorrect views of Japanese history.

Yet deep down, one suspects that Buruma is still emotionally a libertine. That comes through in the vitality of the writing, the loving descriptions of middle-aged strippers and faded vaudevillians playing in theatres smelling of sweat and fried squid. As he admits, “I cannot imagine wanting to immerse myself in a culture without feeling a sensual pull.”

Is it possible for a cosmopolitan to be authentic? Presumably, the missionary in Buruma would believe so, but, as he explains, his old friend Kara would disagree. The icon of the 1970s underground couldn’t stand Japanese who spoke foreign languages too fluently. Truly talented people, he maintained, stuck to their own language. Buruma (who speaks more than a few European and Asian languages) explains Kara’s irritation as stemming from “the idea that a person speaking too fluently in a language other than his native tongue is inauthentic, without a clear identity, an impersonator – ‘a spy’.”

Language is the structure through which we understand the world. It is a powerful force in creating identity, as we know from the numerous political battles that have been fought over it. Japan’s strongest barrier against the rising tide of homogenizing globalization is linguistic. As a society, it refuses to learn to speak English and, like Kara, is suspicious of the few of its citizens who speak it with facility.

Yes, every Japanese child undergoes many years of compulsory education in the subject, but the way it is taught – like a convoluted set of bureaucratic decrees, rather than a tool of communication – guarantees linguistic isolation. While that remains the case, Japan’s cultural specificity – the Otherness that frustrates the missionaries and turns on the libertines – will remain intact.

“Never trust the teller, trust the tale,” was the maxim of British novelist D.H. Lawrence, meaning that a work of art has a deeper reality than the ideas and intentions of its creator. Buruma’s book – beautifully written, funny and painfully self-critical – is not just a colourful memoir of 1970s Japan. It is an open-ended meditation on deracination, identity and the nature of culture, high and low. To put it another way, it is an argument between Buruma, the cosmopolitan missionary, and the Japanese-to-his-fingertips monoglot, Juro Kara.

Following Lawrence, I think that Kara is the winner and Buruma knows it. Now 78 years old, he still puts on phantasmagorical performances by his Red Tent theatre troupe in the grounds of the famed Hanazono Shrine in Shinjuku. The past may be a foreign country, but so can the present be, if you put your mind to it.

*roughly 7.4 m²