Published in The Financial Times April 3rd 2013

Regime shifts in global monetary policy can throw up unexpected winners and losers. Think back to the 1970s when the UK was known as the sick man of Europe. The disease was inflation and the prognosis dire.

Once proud industries like steel and shipbuilding were in terminal decline. Trade union militancy was at its peak, symbolized by the three day week and the winter of discontent.

The stock market reflected these traumatic conditions, with the FTSE 30 index plummeting to twenty year lows. Company finances were in a wretched state. The idea that the UK stock market was offering a once-in-a-lifetime investment opportunity would have been ridiculed.

Yet that was exactly the case. From its nadir to the peak in 2000, the FTSE 30 index rose more than two thousand percent – a performance that investors in today’s BRICs can only dream of.

There are some uniquely British features to this tale, but the big picture was global. Stagflation, labour strife and social fracture had become chronic across the developed world. The UK simply suffered more deeply and for longer.

Real growth in the “resurgent” UK of the 1980s and 1990s was actually lower than in the 1960s. Supply-side reforms were absolutely necessary, but it was the conquest of inflation that powered the UK’s transition from dunce to neo-liberal poster child. And that too was a global phenomenon, driven by the existential threat posed to the capitalist system. The UK just happened to be the most leveraged to the change in priorities.

Now it seems we are in the early stages of another regime shift in monetary policy – from disinflation to aggressive reflation. Again, the nascent consensus is global, driven by the threat that unemployment and debt deflation pose to the system. Again a reversal of fortune is likely for the winners and losers under the ancien régime.

If policy-makers succeed in raising the rate of inflation into the long-term, some high-growth emerging countries could suffer. Amongst the BRICs, Brazil, India and Russia still have structurally high inflation. Amongst the developed countries, it remains to be seen whether the UK’s inflationary tendencies resurface after being subdued for so long.

As for potential winners, the most intriguing candidate is Japan. Like the UK in the 1970s, Japan is the outlier. It had already achieved low inflation by the early 1980s, but the global disinflationary cycle continued for another two decades. Worse, the yen soared in value. These forces drove Japan into fifteen years of falling prices. Today Japan’s nominal GDP is no higher than in 1992.

Now Prime Minister Abe has delighted the markets with his “three arrows” strategy – monetary expansion, fiscal pump-priming and structural reform – which offers the prospect of a decisive break with deflationary stagnation.

What happens when a country emerges from deflation? Memories of the conquest of inflation are still fresh, but for examples of the reverse we have to go back to the 1930s. Interestingly Japan was one of the first to reflate successfully, thanks to Korekiyo Takahashi, minister of finance from 1931 to 1936.

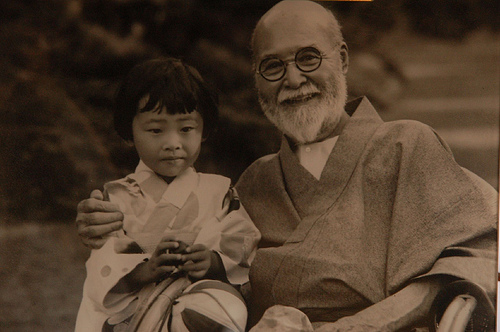

Viscount Takahashi lived an eventful life. The illegitimate son of a painter, at the age of thirteen he travelled to California to study, but was sold into indentured servitude by his homestay family. At the age of fifteen he was living with a geisha, and in his thirties he led a group of hard-drinking, brawling Japanese miners to the high Andes.

Takahashi’s reflationary program involved taking Japan off the gold standard and issuing large amounts of bonds to be bought by the central bank. In today’s terms it combined currency depreciation, fiscal stimulus and open-ended quantitative easing.

The effect was dramatic. Under Takahashi, national income rose 60% while consumer prices rose 18%. The debt-to-GDP ratio stabilized while stocks, which had been in a fifteen year bear market, doubled.

According to Ben Bernanke, Takahashi “brilliantly saved Japan from the world depression.” But there was no happy ending. At the age of 82 he was assassinated by fanatical young officers enraged by his “exit strategy” of cutting military spending. Reflation had achieved its goals and should have been withdrawn. Instead inflation soared under the aegis of irresponsible militarists.

Rightist coup d'etat 2.26.1936

The lesson of Takahashi-nomics is that reflation can take hold quickly if policy-makers are totally committed. But firing just one of Mr. Abe’s arrows is unlikely to suffice, as the UK is currently proving. To secure recovery all three should be fired simultaneously – in Japan and elsewhere too. And needless to say, a clear exit strategy needs to be set out in advance.