Published in Nikkei Asia September 26

During the Pacific War, jazz was banned in Japan because it was considered the enemy’s music. But what did that mean in practice? Not much in places such as a certain disreputable hotel-cum-boarding house in the port city of Kobe on the south coast of Japan’s main island of Honshu. Here, in this warren-like structure, “painted red like some cheap theater,” raucous jazz was often heard.

The residents of the hotel were a motley crew, according to a newly translated memoir. There was an impoverished Egyptian butcher who had occasional windfalls that coincided with a cow disappearing somewhere. There were a dozen “good time girls,” including a middle-aged White Russian, who plied their trade in the watering holes of Kobe.

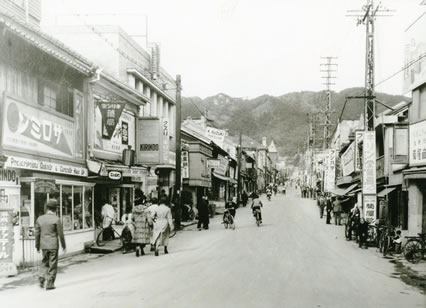

Kobe’s Tor Road in 1936, where the ‘strange hotel’ was located

One of the ladies, known for her intelligence, ambition and physical beauty, was running her own bar at the age of 25, a considerable feat. Later to become famous, at this stage of her career Mama Cherry was obliged to bestow her favors on drunken military police inspectors and other officials. Meanwhile, the jazz played on.

We know all this because one of the two male Japanese occupants of the hotel was Keichoku Saito, who happened to be one of the most important haiku poets of modern times, using the pen name Sanki. Having “escaped” from his family and Tokyo in December 1942, Sanki moved to Kobe on a whim and took the recommendation of a bar hostess for a place to stay. He boarded at the hotel until Kobe was bombed flat in the later stages of World War II

Sanki died in 1962 at the age of 62. His memoir of the era has been published several times in Japanese and was praised as “a masterpiece” by the novelist and critic Hiroyuki Itsuki when it appeared in book form in 1975. The English-language edition was published recently by Isobar Press in a clear and lively translation by Masaya Saito (no relation), with an illuminating introduction. A companion volume features 1,200 of Sanki’s extraordinary haiku, most of them in English for the first time.

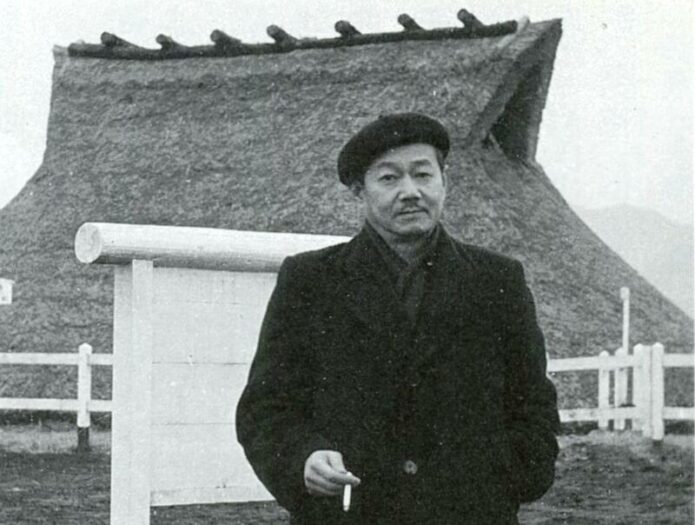

Sanki, in a contemplative mood

The experiences that Sanki relates are variously hilarious, absurd, poignant and horrific. The range of themes evokes Joseph Heller’s great novel “Catch 22.” The collection certainly gives a startlingly different perspective from the home front during the war. Forget about the Japanese propaganda slogans of “100 million with one spirit” and the like. Sanki introduces a cast of mostly penniless characters, himself included, who “believed that freedom, and nothing else, was the highest reason for living.”

The first chapter tells what is coming. Sanki describes a crazy man who would strip off in the street under the hotel window and rotate “spinning rapidly like a living top.” When asked why, he replied that it calmed his disturbed heart. “Two years later,” Sanki writes, “countless incendiary bombs rained down from the heavens on his favorite spot and throughout the city, and as a result, tens of thousands of civilians similarly gyrated as they were stripped naked by the flames.”

The most interesting character is the Sanki that emerges from the pages. In translator Saito’s words, he is a man of many identities — “cosmopolitan, philanderer, libertine, eternal youth, egoist, humanist, nihilist, vagabond.” Sanki came to haiku relatively late, at the age of 33. Before that, he operated a dental clinic in Singapore — though he was best known for his prowess in social dancing, for which he held an instructor’s license.

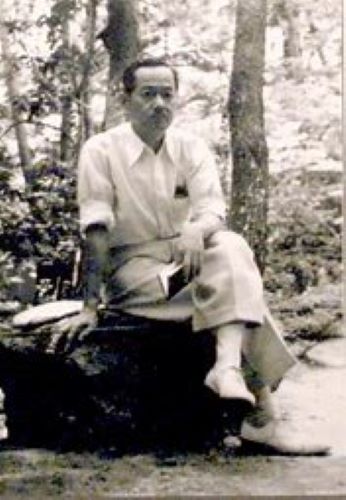

Sanki (r) with fellow poet Tsuguo Ando (l)

Bankrupted by his hedonistic lifestyle, he returned to Japan and ended up as the head of a dental department in a large hospital. By happenstance, a urologist who specialized in sexually transmitted diseases asked him to contribute to a collection of haiku, mostly written by his patients. Sanki had previously considered haiku “antiquated stuff” of little interest, but he was soon hooked and rapidly became a leading light in the avant garde movement known as the New Rising Haiku.

It is common for Japanese poets and literary figures to adopt pen names, and Sanki was no exception — his means “three devils.” Not content with that, he changed the characters of his family name while retaining the pronunciation, so that it meant “East West.” That was perhaps a reference to his cosmopolitanism. As for “three devils,” he did not deny a friend’s suggestion that it stood for womanizing, drinking and gambling.

The gambling, it seems, was of an existential kind. “I gambled my life on haiku,” he wrote. “I didn’t attend to my family at all, and even while neglecting my wife and child and making them suffer poverty, I had no feeling of repentance.”

The Young Turks of the New Rising Haiku movement rebelled against the time-honored conventions of the genre. Specifically, they challenged the idea that haiku should reflect the poet’s lived experience and that references to the natural world were essential, signaled by a recognized “season word.” Instead, they created microfictions, sometimes of a controversial kind, like these haiku by Sanki, published in 1939, just as Japan’s war in China was hotting up.

Screaming

at 10,000 feet

an early death in battle

A machine gun

stutters,

scorpions copulate

Burying a fellow-soldier,

firing a pistol

at the sky

The output of the New Rising Haiku movement had a definite anti-war undercurrent, and in 1940 the Special Higher Police arrested many of its poets, Sanki amongst them. He spent 70 days in confinement, during which he underwent the bizarre experience of having his haiku “analyzed” by a graduate of an agricultural college who had joined the thought police. In the mind of the young inspector, the poem: “Thundery night/an elevator/silently ascending” symbolized the rise of communism in unstable times. Sanki did his best not to laugh.

In the end, the charges against him were dismissed, and Sanki made his move to “the strange hotel” in Kobe. A haiku expert writing many decades later suggested that the thought police went after the New Rising Haiku movement because, having dealt with the Marxists, they were running out of targets and needed to secure their jobs. In reality, Sanki and the others had not broken the laws against subversion, and their poetry, startling as it was, presented little threat to the authorities.

In the words of the translator: “Even though he was barely productive as a poet during the war, it was during his days in Kobe that Sanki began to further mature as a haiku poet. It is often the case that one’s creative energy is honed by extreme hardship.”

To the residents of the hotel, including Namiko, the semi-retired sex worker he lived with, he was a salesman supplying materials to munitions companies — and indeed that was his nominal trade, though business was terrible and he was living in poverty. Nonetheless, he had his share of weird adventures.

One concerned a remarkable middle-aged man called Shirai who learnt how to fly and joined the French air force in World War 1, in which he served alongside Baron Shigeno, a Japanese aviation pioneer. In 1943, Shirai somehow gained access to a military car, festooned with flags, even though he had nothing to do with the war effort. Indeed, he had no job of any sort.

Baron Shigeno, flying in the French airforce, scored two confirmed kills and four probables

What he liked most was driving seriously fast. Having driven the 500 km from Tokyo to Kobe, he planned to “kidnap” his friend Sanki and extend the road trip another 600 km to Hakata. So it was that Sanki found himself “tearing full-tilt like a wild horse through the silence of the scorched land and munching stale bread.”

A different kind of adventure appeared when a nurse who had once tended the gravely ill Sanki asked for a favor. Would he impregnate her, as she wanted to present her ailing mother with a grandchild and there was no other candidate in sight? Sanki was still married, although he had abandoned his wife and children, but he did as asked and even attended a sham wedding party in Nagasaki as the groom

There, he refused the shark sashimi, apparently a local delicacy, but was convinced by his “bride” to sample some supposedly delicious out-of-season oysters. The result was an agonizing bout of gastroenteritis. Happily, the old lady did see the face of her grandchild before she passed on.

As the American bombing raids intensified, it became clear that Kobe would not be spared. Several residents took protective measures, but many did not, either because they did not want to abandon friends and relatives or out of sheer fatalism. Sanki left the hotel and moved, with Namiko and some others, to a crumbling mansion high up the mountain behind the port. It was there that he saw the end of the war and returned to writing haiku, which emerged, as he puts it, “with an explosive force.”

The fire-bombing of Kobe in 1945

Mama Cherry tried to talk him into turning “Sanki Mansion” into a female-run brothel. It would be several cuts above the “barbaric” comfort station set up for the American military, which offered no privacy and overflowed with sewage. But Sanki pulled out of the deal, causing her to retort “that is why Sensei (Teacher) is a failure.”

The next time he heard of her was 18 years later when he scanned a newspaper. She had become the proprietor of the Copacabana in Tokyo, the glitziest and most exclusive club in Asia, patronized by Japanese powerbrokers and foreign dignitaries like King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. Entertainment was supplied by the likes of Nat King Cole and Dean Martin. Such was her fame that a movie, “Fighting Fish at Night,” was made of her story in 1959. As for Namiko, she moved back to Yokohama shortly after the end of the war, married a black G.I. and migrated to the U.S.

The war turned out to be a springboard for Sanki too, as he became a prolific and respected haiku master. As Saito notes, his haiku became more introspective, no longer fictional, and usually contained a season word. He had found a way to link his vision with the tradition.

My country in hunger

I too stand

watching a winter rainbow

How awesome are

women’s breasts

summer has come

Rainy season

a horse neighs behind

the insane asylum

All in all, the existential gamble had worked for him — and his memoir is now finding a new audience.

“The Kobe Hotel: Memoirs,” by Sanki Saito, translated by Masaya Saito, Isobar Press, 2024