Published in Japan Forward 2/10 /2024

Richard Nathan is the brains behind the Red Circle imprint which has published short fiction by Japanese authors of the calibre of Kazufumi Shiraishi, Soji Shimada and Kanji Hanawa. What makes his offerings unique is that the stories have never been previously published in English or Japanese. That tells you a) he is well plugged into the world of Japanese writers and publishers, and b) he is very persuasive.

Now Nathan has turned from poacher to gamekeeper, or should it be from gamekeeper to poacher, by writing a book of his own. As you would expect from a man who comes up with such section headings as “Booze, Books and Bonking” and “Cats, Tatts and Christians”, it is no dry-as-dust academic tome. Rather, he takes us on a highly personal wander through the highways and byways of Japan’s literary culture, from the eleventh century “Tale of Genji” to the contemporary self-help book “The Courage to be Disliked.”

Following the tradition of “zuihitsu” (“wandering pen”, meaning loosely connected ideas), Nathan digresses with delight. Not content to make a lengthy comparison of the feline narrator of Natsume Soseki’s famous novel I Am A Cat with the totally hypothetical moggy used in Schrodinger’s quantum mechanics thought experiment, he also shoe-horns David Bowie’s “cat from Japan” into the mix. It’s that kind of book.

Bowie in kimono designed by Kansai Yamamoto

Full disclosure: Nathan mentions me in the credits though I had no inkling of that until I opened the book in order to write this review. I certainly gleaned a lot of new information from the content.

I had no idea that Winston Churchill had a tattoo (Nathan doesn’t say where); that the 1959 Isewan Typhoon had such a marked effect on Japan’s literary production, mainly via the 1970s TV series Akai Unmei (“Red Fate”); that renowned scholar Donald Keene considered that Japan “deserved” to win the Pacific War; that “Alice’ s Adventures in Wonderland” has been translated into Japanese more times than into any other language; that Marquis de Sade translator Tatsuhiko Shibusawa was a relative of Eiichi Shibusawa, the legendary businessman whose portrait is to be found on the new ten thousand yen note.

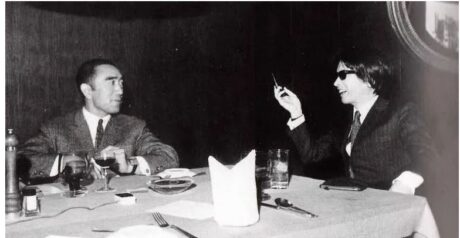

Tatsuhiko Shibusawa (r) with his pal Yukio Mishima (l)

The “Booze” chapter is one of the best, allowing Nathan to display some impressive research skills. He describes a limited circulation monthly magazine called “Foreign Liquor Heaven” which was published from 1956 to 1963 by a drinks company called Kotobuki, now known as Suntory. A top-class production with fiction from the likes of Dorothy Sayers and sophisticated content and lay-out, as well as a few tasteful nudes, it had some of the ambience of the early Playboy, according to Nathan’s account. It was the brainchild of Takeshi Kaiko, a member of the advertising department who was soon to win the Akutagawa Prize for the best novel from a new writer and become a national figure for his reportage from the Vietnam war.

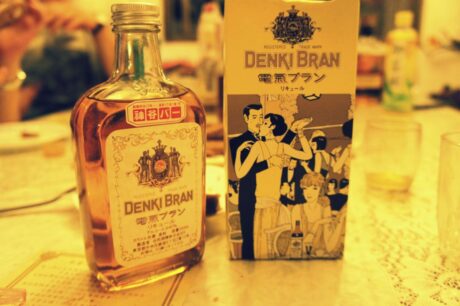

Nathan has also engaged in a more direct form of research into the nexus between booze and books. He has swilled down that notorious potion Denki Bran (“Electric Brandy”) at the Kamiya bar in Asakusa, as consumed by bad boy novelist Osamu Dazai eighty odd years ago. As our guide notes, it’s worth sampling once for the experience, but beware. Regular tippling may turn you into a worse wreck than morphine addict and serial double suicide practitioner Dazai (usually the girlfriends died, he survived), though without his remarkable literary legacy.

Nathan then takes us down a dimly-lit side street to a tiny bar – he is careful not to specify the location – barely marked by a blurry Suntory Whisky sign. The proprietor is an elderly lady who has seen writers come and go through the decades. Perched on a barstool is Mitsuyo Kakuta, one of Japan’s most widely read novelists and the latest in a long line given the task of producing a modern version of “The Tale of Genji”.

This is what she said, as channelled by Nathan. “What you should be asking is not why Japan is like this, but why nowhere else is. Why can’t women outside Japan come to a bar alone and drink and leave safely taking the train home, and why shouldn’t a widowed octogenarian run a tiny bar single-handedly in a metropolis well into the night if she wants to? What is odd about that?” Indeed!

A healthier theme is sport, with an emphasis on running. Best-selling novelist Haruki Murakami is well-known for his marathon-running and has written a book on the subject. The aforementioned Mitsuyo Kakuta also runs two or three marathons a year, and Nathan lists several other sporty writers. Appropriately in the year in which the first British ekiden (long-distance relay race) took place, Nathan digs into the history of long distance running in Japan, taking in its role as a vital communications tool in medieval times and examining the many stories in various media that have featured the ekiden and other races.

The most extraordinary story of all involves Shizo Kanakuri, the founder of the Hakone ekiden, the most prestigious of them all. As a young man, he took part in the marathon at the Stockholm Olympics of 1912. Unfortunately, due to terrible weather conditions and a gruelling journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway, he passed out halfway through and returned to Japan without notifying the officials. As a result, he was classified as “a lost runner” who had not finished his race. In 1967, he was invited to complete his marathon. He duly did so with a time of 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours and 32 minutes, during which he had six children and ten grandchildren.

This series of events must have inspired the master of surreal science fiction Yasutaka Tsutsui to write the short story “Running Man”. In this future world, nobody has any interest in the Olympic Games and the few runners routinely get lost for decades while the aging officials wait endlessly.

“The podium actually consisted of three boxes made of flimsy plywood, exposed to wind and rain for so many years that they were ready to collapse. I approached the senior official as we carried them back to the office. “Maybe the one who went to sea was different,” I said. “But the runner who died must have intended to finish the race.”

The official snorted.” I suppose he must.”

“In that case, according to the Olympic spirit, he should be awarded second place.”

“That’s also true. Let’s make him runner-up.”

As we know from recent Games, the Olympic spirit is ever adaptive.

Yasutaka Tsutsui

Nathan’s book comes in five discrete sections, but, as the author explains, the sections can be read on a stand-alone basis. The organizing principle, insofar as there is one, is the metaphor of the kaleidoscope – shake it and you have a different reality. Nathan informs us that kaleidoscopes appeared in Japan just a few years after Scots inventor David Brewster patented the device in 1817. In Japan, it is usually known as a mangekyo, which means literally “ten thousand flower mirrors.”

They are plentiful today. A speciality kaleidoscope shop in Tokyo’s posh Azabu-Juban neighbourhood is frequented by fans of “Sailor Moon” – the Sailor Moon character wields a magic kaleidoscope, and the author of the manga and anime series bought one there. On a more literary note, the famed writer Jakucho Setouchi – described accurately by Nathan as “wild child turned Buddhist nun” – helmed a multi-author book called Inochi Mangekyo (“Life Kaleidoscope”) in 1991.

What stands out from Richard Nathan’s book is his enthusiasm and optimism, for Japanese literature high and low, and for Japanese culture in general. His book is not one that should be swallowed in one gulp, which is definitely the best way to drink Denki Bran. Rather, it should be taken in sips over a long period, as you would enjoy a vintage Suntory Yamazaki in a favourite bar.