Published in Japan Forward 22/7/2021

The Witches of the Orient (directed by Julien Faraut, 2021).

“We thought we would have to leave the country if we lost,” recollects a member of the female volleyball team that represented Japan at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. “We seriously talked about going to Romania.”

Some highly remunerated present-day sports stars complain about the mental stress they undergo. Imagine the weight of expectation on this group of young factory workers nineteen years after the end of World War Two.

Japan had proposed two new sports to be added to the Olympic roster – judo, Japan’s national sport, and volleyball. Earlier in the day of their final, the female volleyballers had watched Japan’s open weight judo champion being crushed, quite literally, by the much bigger Dutchman, Anton Geesink, in the hallowed grounds of the Kodokan, the Mecca of judo.

The whole idea of judo is that technique and konjo (fighting spirit) beat bulk and muscle, but Geesink’s victory put that principle in doubt. Volleyball, on the other hand, clearly favours the physical attribute of height. For the shorter, slighter Japanese players to triumph over the Soviet Union’s team would require buckets of konjo, impeccable technique and new, creative tactics.

As history tells, the “witches” delivered and wiped away the humiliation of the judo defeat.

Not only did they beat the Soviets under the gaze of then Crown Princess Michiko and set off a multi-decade boom in volleyball. Not only did 67% of TV-owning households tune in to the match from the beginning, with 85% watching the climactic minutes, thus creating a national moment that validated sport as a symbol of communal identity.

Perhaps most important of all, they showed that konjo really does work when applied intelligently.

Japan’s female volleyball team were first dubbed “witches of the orient” by the Soviet press during their three month tour of Europe in 1961 – though the Russian word used (charodeika) can also mean “fairy”.

Given the standard depictions of witches in the media, it didn’t seem a flattering designation when picked up by Japanese reporters. But to director Julien Faraut, it had a positive vibe.

In a recent interview, he states “I love to see people that practically have supernatural powers, because they are the only people in the world that can achieve such moves and creativity in their sport.”

All of the witches worked for the textile company Nichibo (now Unitika), which was renowned for its volleyball team. Despite their sporting prowess, the athletes received no special treatment. They were required to be ready for a day’s work in the factory at 8 a.m., although intensive training sessions, supervised by their legendary coach Hirofumi Daimatsu, went on deep into the night and, on occasions, until dawn.

In early 1964, the American magazine Sports Illustrated ran an exposé on the team titled “Driven Beyond Dignity.” Reaching back to wartime stereotypes, the journalist pronounced himself “chilled by the fanatical striving” and “the grim wild eyed intensity of the coach.”

In the above interview, Faraut offers a totally different perspective. In contrast to the usual narrative about Japan’s “backward” treatment of women, he notes that in those days female athletes in the west were not supposed to undergo the same gruelling training sessions as men.

In other words, Coach Daimatsu was a pioneer in the field of women’s sport. Interestingly, in the UK the film is being distributed by Modern Films, a company dedicated to female empowerment.

Daimatsu was known as a “demon” in Japan, but Japanese demons are not necessarily evil or dangerous. Anyone who is single-minded or meticulous can be described as one. In the case of a top-level sports coach, it’s a compliment.

After joining Nichibo in 1941, Daimatsu was drafted into the Japanese army and found himself in the middle of Japan’s disastrous Imphal campaign in Burma. One of the few survivors, he made his way along the “white bones road” back to Thailand and post-war life. Despite the rigour of his training regime, he was soft-spoken and calm.

As several team-members noted, he was a handsome man. The volleyballers were mostly war babies. One was born in an air-raid shelter. Of the six witches who played in the final, only two had both parents alive. From the way they talk about him today, it is clear that they saw him as a father figure. Not one has a bad word to say about him and his methods.

Sadly, Daimatsu passed away fourteen years after the Olympic triumph. In the film, there is a haunting expression on his face as the team members celebrate with tears of joy. He doesn’t move. He doesn’t smile. He doesn’t look happy at all. Perhaps he was imagining life without a goal to inspire him. Perhaps he was imagining a society without a goal to inspire it.

Unquestionably, Daimatsu was a brilliant and innovative coach. He came up with the “rolling receive” tactic, apparently a taking hint from wooden “Daruma” dolls which bounce back when tipped over.

More important, he instilled a huge dose of konjo in the team – or what might be called “winning mentality,” a trait shared by the greats in all sports.

“We were confident we were going to win,” says the late Kinuko Tanida. “It was due to the discipline and harshness of the training sessions that we became so strong.”

Faraut is in charge of the film archive at the French Institute of Sport, but is also an acolyte of Chris Marker, the great avant garde director and Japanophile. His first film, A New Look at Olympia ’52, is a homage to Marker that includes footage of Marker’s rarely seen documentary on the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki. Faraut’s 2018 release, John McEnroe: In The Realm of Perfection, portrays the tennis champion as a kind of performance artist.

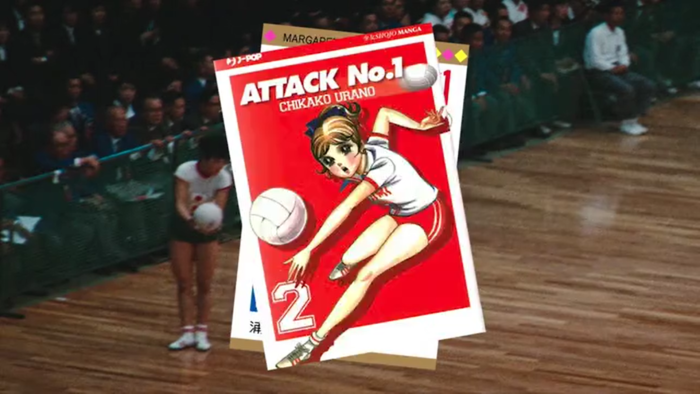

The Witches of the Orient is no ordinary sports documentary either. There is no voice-over, but plenty of throbbing music to convey the atmosphere. Faraut mashes up revealing and inspiring interview footage of the surviving team members today, extracts from the Japanese volleyball anime which he watched as a boy in the 1980s and colour film of the witches training in the early sixties.

Those scenes were taken from a short film by female director Nobuko Shibuya which was shown at Cannes in 1964. Faraut adds some computer-generated trickery to create an astonishing sequence that cuts rapidly between anime and Daimatsu hurling volleyballs at the witches like grenades.

Appropriately, the musical backing is Machine Gun by UK trip-hop band Portishead. In a recent live Q&A, Faraut spoke of a “female dimension” shared by the witches and Portishead’s introverted but powerful singer, Beth Gibbons.

He clearly enjoys overturning gender stereotypes, as in the opening sequence of a cartoon samurai rushing to save a helpless lady from a monster. Reality can be very different from expectations, as the unfortunate samurai finds out.

Author Robert Whiting was at the 1964 Olympics. In his recently published memoir, Tokyo Junkie, he recalls the witches as follows: “their bruising eleven-hour-a-day practice regimen over a period of two years was seen to symbolize the dogged resurgence of the Japanese economy, short on resources but full of fighting spirit.”

The witches and their demon coach certainly had a galvanizing effect on Japan and the wider world, to the extent that a young French movie director chose to film their story over half a century later. Not as an exercise in nostalgia, but as a celebration of the enduring magic of sport – and, by extension, human possibility.