“Come to me all ye who are weary and burdened and I will –“

“Jesus Christ!” the marketing director yelled in bewilderment.

“Ask him to leave,” said the president. “God has no place in commerce.”

“Agreed. If we had Jesus on our board, we’d be even deeper in the red,” the financial director whined. “He’s the friend of the poor, isn’t he? He’d only end up siding with the union.”

The marketing director hurriedly dowsed the fire with another cup of water, and Jesus disappeared without a trace.

It’s mystery why some quite bland Japanese authors enjoy extraordinary global acclaim, even to the extent of being considered potential Nobel laureates, while other, more creative spirits remain untranslated and unknown to foreign readers.

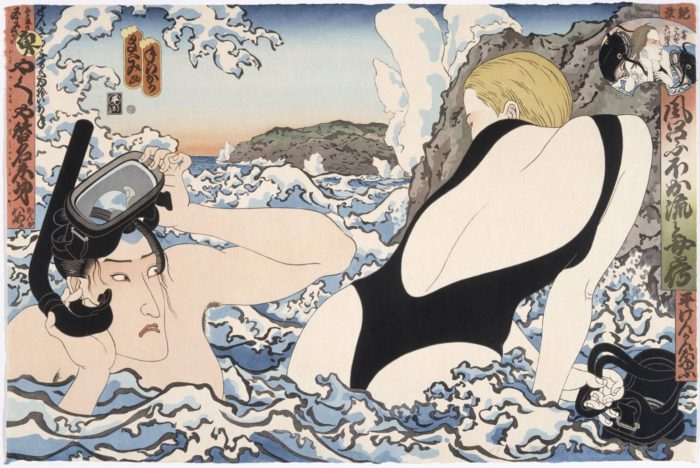

Yasutaka Tsutsui languished in the latter category for too long. Fortunately, more of this great Japanese writer’s work is becoming available in English. The latest example is Bullseye!, a collection of twenty short stories selected from different stages of Tsutsui’s long career.

The subjects range from murderous geriatrics to sex robots, from a death clock to an Olympic marathon that goes on for half a century with nobody caring.

You can buy it here.

Also highly recommended is its predecessor, Salmonella Men on Planet Porno. The title story offers a bizarre take on evolutionary theory. Rumours About Me, written in 1979, anticipates the world of reality TV and the extinction of privacy. In both cases, the translation by Andrew Driver is clear and natural.

You can buy that one here.

So what kind of writer is Tsutsui? Imagine a cross between J.G. Ballard and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, with elements of Kafka, Saki and magical realism thrown in.

A celebrated author in Japan since his breakthrough in the mid-1960s, Tsutsui is extraordinarily prolific. His published oeuvre runs into three figures, including novels, essay collections and the volumes of short stories for which he is probably best known. Dozens of films and TV dramas have been made from his works. He is also a playwright and actor.

Tsutsui with the director and voice artists of the anime version of his story Paprika. The film was nominated for the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival of 2006.

Tsutsui’s literary territory runs from science fiction, the genre that gave him his start as a writer, to social satire, surrealism and meta-fiction. He has also produced Georges Perec-style experimentalism, such as a novel which uses one less syllabic character in each successive chapter, leading to the total loss of language and the end of the human world.

Most of Tsutsui’s work fizzes with humour, but as translator Andrew Driver notes, his recent stories are darker, often dealing with themes such as ageing and death – though never in a conventional way. His style has become more literary and allusive too.

Tsutsui the Provocateur

A certified member of the awkward squad, Tsutsui was at the centre of a heated controversy about political correctness in the early 1990s. For several years he gave up writing in protest against the treatment he and his family had received at the hands of activist groups and fellow writers. Fortunately, the self-imposed ban didn’t last long.

For better or worse, the 82-year old Tsutsui’s trouble-making instincts are still intact. Earlier this year he caused outrage with an “obscene” tweet about the statue of a comfort woman in South Korea. His Korean publisher immediately ceased sales of his latest book.

The comment, intended as a joke, was certainly in bad taste, but in no way is Tsutsui a nationalist or anti-Korean, as his later remarks made plain. He is, however, instinctively transgressive in the French surrealist tradition of Georges Bataille and Le Chien Andalou. He uses humour aggressively, to subvert reality and normality.

Tsutsui. in the film version of his story Everywhere Else But Japan Sinks, a parody of the disaster novel / movie Japan Sinks!

Tsutsui studied psychology at university and his graduation thesis was entitled “A critical analysis of the creative psychology of surrealism.” His influences include Schopenhauer, Sartre and the Marx Brothers.

Driver quotes an interview with Tsutsui in the introduction to Bullseye!. “To me, science fiction is just another way of deconstructing reality, just as surrealism was… When I was at university, I wanted to be a comic actor. That seemed to be another way to deconstruct reality. Comedy was very important to me.”

In Tsutsui’s world, men can give birth, a sex robot may not be a robot and death turns out be a smiling man in a beige coat. But don’t bother travelling to Mars for a change of scenery. It’s no better than here.

There was no religion on Mars; there were no heroes. Instead there was a gaggle of B-list celebs, empty-headed idiots who perpetually courted fame and were constantly hounded by the media. In so many ways, young people born on Mars thirsted for a strong influential leader who would show them the way. The way to what? They didn’t even know.