Published in Newsweek Japan 10/7/2018

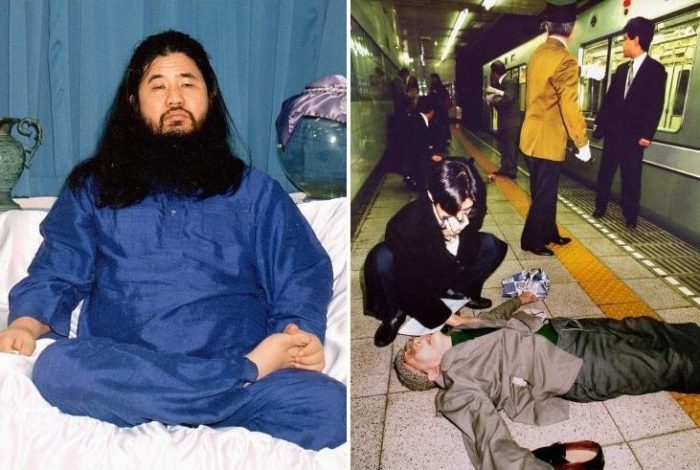

Aum My God! Memories of the terrible events of March 1995 came flooding back when I heard the recent reports of the execution of Aum Shinrikyo leader Shoko Asahara and six of his senior disciples.

My three year old daughter was travelling on the Tokyo subway with her nursery class that morning. Fortunately the deadly sarin attack happened sometime later, but the sense of shock still remains deep today.

Japan was famed for its high levels of public safety, yet here was a terrorist outrage in the centre of Tokyo carried out by Japanese citizens. Not just ordinary citizens, but scientists and graduates of top universities, class-mates and friends of Japan’s future governing elite.

This struck me as significant. In the early nineties Japan had already experienced the collapse of various “myths” – the myth that real estate prices would always rise, the myth that far-sighted bureaucrats would steer the economy to a glorious future; the myth that ninety percent of the population was middle-class. Now here was another busted myth; that the education system graded people correctly and graduates of famous universities were automatically worthy of respect.

When Newsweek Japan asked me to write an article on the incident, I stressed the point of difference with religious cults in Western countries, which usually gather their members from the lost souls of society. Aum offered its members a system of belief and a sense of identity forged in confrontation with outside forces. Unquestioning obedience was demanded and proven by going to lengths beyond the boundaries of common sense.

In that sense, Aum was a malevolent version of other reality-defying Japanese elite institutions – the banks, the financial bureaucracies, the blue chip companies – which were fiercely resistant to outsiders and demanded submission of the individual to the collective, sometimes in disregard of moral and legal constraints.

From the perspective of the present, things look rather different. Firstly, Japan has changed for the better. The corporate sector – including the banks – has become more accountable and transparent. Amongst the public, scepticism is prevalent. Nobody believes that bureaucrats can bring about higher economic growth through planning it – though they might be able to bring about lower growth. The idea that Japan is a homogenous middle-class society is long gone; take a look at its Gini co-efficient, which is above the OECD average, or at Hirokazu Koreeda’s Shoplifters, which just won the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Secondly, the contrast to Western norms was, in retrospect, overly simplistic. Some foreign cults, notably Scientology, attract powerful people such as Hollywood celebrities. More to the point, the distinction between religious and political cults is an artificial one and it is the latter variety which attracts godless Western intellectuals. It was not ordinary middle class citizens who chose to betray their country to Stalin’s Soviet Union, but elite graduates of Cambridge University. Likewise, the famed French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre ardently supported Mao Zedong at the time of his greatest excesses of violence and destruction.

Highly educated people everywhere, not just in Japan, often lack a grounding in reality and are suckers for the certainty of cult-like intellectual systems and groupings. Not for nothing was communism described, in the title of a 1949 book written by ex-communists, as “the god that failed.”

Thirdly, the Aum attack came at a particular historical moment for Japan, a time when the euphoria of the bubble era had disappeared and much harder times were setting in. It seemed a uniquely Japanese phenomenon, but the entire developed world was to face a similar reckoning with the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Japan, it turned out, was simply leading the way.

As is usually the case with such events, the damage has been not just economic, but also social, political and psychological. Already, there has been a rise in terrorism, gun rampages, conspiracy theorizing, ethnic strife and political fracture. Thousands of European citizens have volunteered to fight for Islamic State; mostly no-hopers, but also including doctors, students at top universities and “Jihad Jack,” a white schoolboy from the best state school in Oxford.

The “shinri” in “Aum Shinrikyo” means truth. In times of shattered presumptions and moral confusion, that is a product in high demand. Cults, both religious and political, will always be there to supply their version.

The next Shoko Asahara could be a global figure – and have methods of delivering destruction that his dead predecessor could hardly imagine.