Published in Japan Forward 12/4/2021

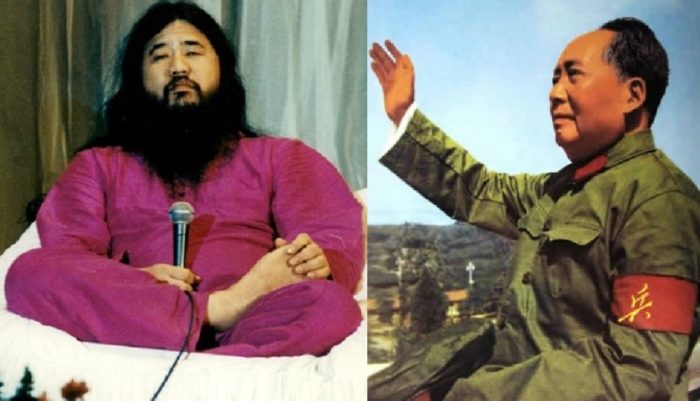

At the time, it seemed more like the plot of a bad James Bond movie than everyday reality. Imagine an obese, bearded guru with fifty wives who claims he can float in mid-air. Add a heavily guarded headquarters near Mount Fuji where scientists work tirelessly to develop chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. Throw in a giant microwave oven to get rid of the corpses of the guru’s enemies.

Bond villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld would have felt right at home.

Yet the human damage was all too real. On March 20th 1995, Aum Shinrikyo attacked Tokyo’s Kasumigaseki subway station with sarin, a deadly nerve gas. Thirteen unsuspecting commuters were to die agonizing deaths and over 6,000 would be injured, some suffering lasting brain damage. Thirteen cultists, including guru Shoko Asahara, were eventually executed in 2018 for their part in this act of indiscriminate terrorism.

The director of the documentary film AGANAI, Atsushi Sakahara, was in Kasumigaseki station on that fateful day in 1995. He inhaled the toxic fumes and has been living with the physical and mental consequences ever since. In a strange twist, he went on to marry a woman who he subsequently discovered to have been a fringe member of Aum. It comes as no surprise that the marriage did not last.

AGANAI has been well received in various overseas film festivals. Perhaps because it was partly financed by a Hong Kong production company, it comes with English language subtitles even in Japan. That is good – the film deserves wider exposure. Although it tackles one of the most notorious events in recent Japanese history, it has a disturbing message about human nature that has universal significance.

There are two kinds of documentary film. The traditional type assumes an uninvolved, “objective” approach to its material. Then there is the interventionist type, exemplified by the work of Michael Moore, in which the filmmaker enters the world of the film as protagonist and provocateur. AGANAI is very much of that latter type. It consists of a series of conversations between Sakahara and Hiroshi Araki, the head of public relations at Aleph, as the Aum cult now calls itself.

If that sounds boring, it is anything but. The air crackles with tension as the two men engage in mind-games and soul-searching and delve deep into their own pasts. They have some things in common. Natives of the Kansai region, they both studied at Kyoto University in the late 1980s. Both were there when the red-robed Asahara arrived at the campus in a chauffeur-driven limo, hoping to attract highly educated recruits. The future film director yelled out “Go ahead and levitate.” Araki attended the guru’s lecture and was duly hooked. As the ancient Greeks insisted, character is fate.

In his programme notes, Kasahara describes the film as a “road movie.” Like all the best examples of the genre, it features a journey that is metaphorical as well as physical. Together the duo revisit Kyoto University and familiar countryside. Araki proves unusually adept at skipping pebbles in a lake near his grandmother’s house, but breaks down when recalling an illness of his younger brother that was potentially life-threatening but turned out to be trivial. Confronting the reality of life and death in this world was unbearable to him.

Unlike Robert de Niro and Charles Grodin in Midnight Run (1988), which is Kasahara’s favourite road movie, the two men can never be true buddies. AGANAI’s opening sequence – news footage of the mass murder at Kasumigaseki – ensures that.

“Aganai” is the Japanese word for atonement. Kasahara explains that by making the film he is atoning for his failed marriage and the suicide of a close friend that he was unable to prevent. In the course of the film, he forcibly confronts Araki with the need to atone for the crimes of Aum – in which the senior cultist has been passively complicit after the fact. We see posters of Asahara on the walls of the Aum / Aleph headquarters a decade after his guilt was established in court.

Araki joined Aum in 1992, several years after Asahara returned from a trip to Tibet determined to implement his interpretation of Vajrayana, an esoteric form of Buddhism. The guru chose to take literally texts that are usually considered symbolic, such as this from the Hevajra tantra – “you should kill living beings, speak lying words, take what is not given, consort with the women of others.”

In 1990, an Aum hit-squad broke into the house of a lawyer acting for the relatives of cultists and, on Asahara’s specific instructions, murdered him, his wife and young son. The bodies were buried in remote areas, with faces and teeth smashed to prevent identification. Other killings followed, supposedly required by Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and creation repurposed by Asahara to suit his apocalyptic agenda.

Araki would not have known about that, but the paranoia and psychosis must have been noticeable to anyone willing to notice it. Film director Kasahara extracts one startling admission from Araki: the current head of public relations would not have joined the cult after the sarin attack. But as for leaving now, it seems unlikely. Aum / Aleph is his whole world. It has made him what he is. As Kasahara’s probing makes clear, Araki was a weak and frightened soul from an early age, which made him a natural recruit for Aum.

To the western eye, it seems strange that a religious cult could attract masters students at prestigious universities and doctors and scientists. There were also sympathizers in the police, even in a TV network, where supporters managed to insert subliminal images of Asahara into a children’s cartoon.

Does that mean that highly educated Japanese are more gullible than highly educated Westerners? Not necessarily. Western elites tend to be less religious than the general population of their countries, but their record of falling for simple totalizing belief systems is appalling. If we broaden the concept of religion to include political dreamlands, the differences disappear.

It wasn’t truck-drivers and miners who idolized the psychopathic Mao Zedong, but Nobel Prize-winner Jean-Paul Sartre and distinguished American academics, some of whom defend Mao and his cultural revolution to this day. The limits of such delusions were exemplified by the radical British academic Malcolm Caldwell, a staunch supporter of Pol Pot who defended the Cambodian dictator from accusations of mass murder. Invited to Cambodia, he was shot to death by Pol Pot’s men a few hours after interviewing the creator of the “killing fields.”

Simon Leys, the Belgian-Australian sinologist, saw through Mao from on an early stage. This is his view of the dictator’s admirers, at home and abroad –

“What people believe is essentially what they wish to believe. They cultivate illusions out of idealism—and also out of cynicism… They believe because they are stupid, and also because they are clever. Simply, they believe in order to survive. And because they need to survive, sometimes they could gladly kill whoever has the insensitivity, cruelty, and inhumanity to deny them their life-supporting lies.’“ Simon Leys: the New York Review of Books, July 20 1989.

Not a comforting view of human nature, but one that matches the historical record in relation to Mao Tse Tung, Pol Pot, Shoko Asahara and many others.

Director Kasahara chose to write “aganai” in capitalized Roman letters. In the programme notes, he comes up with some wordplay. “Ai ga nai” means “there is no love.” Replace the first word with the English “I”, and you get “there is no me.” One near-anagram that immediately strikes the eye is “again.”

Could an Aum-like phenomenon appear again? If Simon Leys is right, the answer is yes. The human capacity for self-delusion is endless. But where and in what form is anyone’s guess.