Published in Nikkei Asia 26/4/2023

“There is nothing–absolutely nothing–half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats,” said our captain, echoing the famous words of the water-rat in Kenneth Graham’s children’s story The Wind in the Willows.

Who would argue with that on a fine afternoon with the late cherries in bloom and our Jolly Roger pennant flapping proudly in the breeze? It certainly beat sitting in an office and gazing at a screen, even for a hopeless landlubber like me.

Our plan was to experience Tokyo from a different vantage point, travelling through its rivers, canals and bay. In doing so, we were taking the advice of Professor Hidenobu Jinnai of Hosei University.

In his book Tokyo A Spatial Anthropology, he wrote. “When viewed from the water, the whole city appears strikingly new. In order to read back through the accumulated layers of history… a water route proves far more effective and engrossing than travel by land.”

The vehicle that we hired was a nifty 23 foot Yamaha motor boat capable of getting fourteen knots out of its outboard engine. All five of my companions were experienced sailors, though our fearless captain was the only one with a Japanese boat licence. The job of the rest of us was to give him advice, which he invariably ignored, and hand him his wine when he needed it.

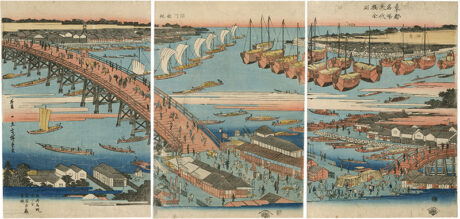

The vibe was more Top Gun than Wind in the Willows as we surged down the Sumida River, burning off slower moving craft and leaving a V-shaped wake. Our captain, who I shall call ‘Maverick’ after the character in the 1986 movie, then veered to the right and announced we were heading for Nihonbashi, the most famous bridge in Japan, first built in the early seventeenth century.

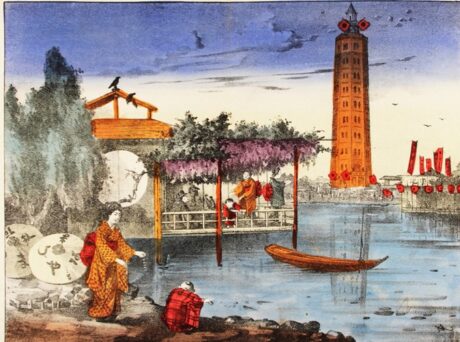

We passed a few yakatabune leisure barges – mobile venues for revelry with geisha in bygone times, now used mainly for the tourist trade and corporate junkets. There were also quite a few classy leisure craft moored at a purpose-made jetty, but not as many as you might expect in a city as large and rich as Tokyo. Perhaps, the boat boom is yet to come.

As we progressed into the heart of the financial district, the waterways grew narrower and the bridges significantly lower.

“Looks like the tide’s rising”, Maverick drawled as we approached a semi-circular stone bridge. “Reckon we can get through?”

“Unlikely,” replied one of our number who I will call ‘Iceman’. “We’d better turn back.” That made sense. Getting stuck under the bridge and having to call for help would not be a good look – and would likely cost money.

Maverick nodded thoughtfully and carried on regardless, aiming for the centre of the bridge. His judgement was perfect. We came out the other side with at least two inches of clearance. Our Jolly Roger pennant stood straight and tall.

Soon we were gliding past the Tokyo Stock Exchange and looking up at the stone gryphons of Nihonbashi itself. This is Japan’s point zero, the spot from which all distances to Tokyo are measured.

I worked in a nearby office for several years and never gave a second thought to what lay under the bridge. In fact, I barely took notice of the bridge itself which was a sorry sight with an ugly expressway crammed on top of it, part of the construction boom preceding the 1964 Olympics.

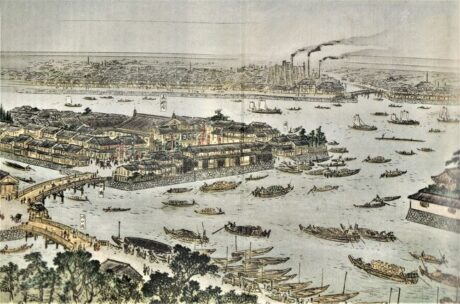

Yet Tokyo’s waterways are living history. The city could not have become what it is today without them. At the start of the Edo period (1600-1868), so termed after the old name for Tokyo, it was a quiet fishing town with a coastline at Hibiya, now home to the Imperial Hotel. By the early eighteenth century it was a metropolis that supported a million people, making it the world’s largest city.

The logistics of bringing in food and other necessaries would have been formidable. In a world without trucks and trains, most of it was done by water. Rice and other agricultural products would be transported by river from agricultural communities to the north, lumber and other items by sea from more distant parts of Japan.

Barges had deliveries to make in the other direction too, gathering the “night soil” from every household and taking it to the farmers for use as fertilizer. This unique recycling system, based on financial incentives, kept the city hygienic in pre-modern times.

In 1877, R.W. Atkins of Tokyo University concluded that in the decade just after the Meiji Restoration Tokyo had a water supply purer than London’s.

Professor Jinnai mourned the loss of “the city of water” and its transformation in modern times into “a city of land.”

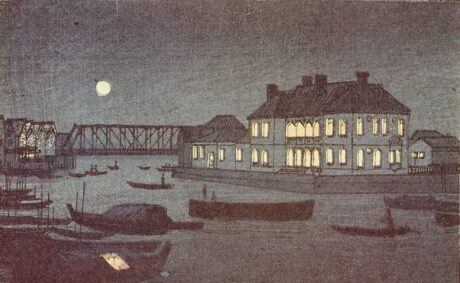

“It is all but forgotten today that Tokyo’s low city was once a city equal to Venice in its charms,” he wrote. “The beauty of the water’s edge was a favourite subject for woodblock print artists beginning with Hiroshige…The business of the low city grew along axes formed by the canals and rivers. The economic, social and cultural life of the city developed in close connection with the water… Most of the theatres of Edo and early Meiji Tokyo, for example, were located near water.”

Jinnai wrote those words in 1985 when the low city, meaning the eastern, working-class area, was at its most dilapidated. The waterfront itself was a mess of aged warehouses and industrial plants belonging to companies such as Tokyo Gas and engineer IHI. Since then, there have been big changes, starting in the 1990s.

As in London, the previously dowdy east of the city has been revived by an influx of hipsters and creative spirits and the whole waterfront has been turned into high end apartments, shopping meccas and places of entertainment – such as the theatre where Bob Dylan recently put on four concerts.

Maverick’s next move was to take us out to the bay, under the Rainbow Bridge and in the direction of Haneda Airport. The waves were choppy here, so canned chuhai cocktails were a better option than wine. It was also advisable to grasp something sturdy and metallic if you didn’t want a close encounter with the wet stuff.

Tokyo has long since lost its position as east Japan’s premier port to Yokohama, which was a mere village in the Edo era. Even so, there was plenty going on in the bay – huge container ships unloading, other ships being repaired, passenger ferries heading for Oshima and other outlying isles which are administratively part of Tokyo. The process of landfilling still goes on too, with large, barge-like craft dumping their loads in the designated spots.

It was the first Edo Shogun, Ieyasu Tokugawa, who imagined the giant city into being, pushing back the shoreline, creating a network of canals and diverting mighty rivers in order to turn uninhabitable flood plain into rich agricultural land. It has been spreading and shape-shifting ever since.

The waterfront that we observed as we made our return journey was totally different from what it looked like in 1985, which in turn would have been unrecognizable to someone in 1935. No doubt, the view will have morphed again significantly in another fifty years.

In his book, Professor Jinnai describes a trip he made around the waterways as “one of the best forms of amusement that Tokyo has to offer.”

Our pirate band would drink to that. In fact, that’s exactly what we did as Maverick locked the wheel into a slow circular motion a few hundred yards from the marina and we sipped the last of our wine and enjoyed our final moments on the city of water.

As Ratty said, there’s nothing quite like messing around in boats.