Published in Japan Forward 6/4/2022

Joan Miro and Japan, the current exhibition at Bunkamura in Shibuya, is well worth attending – even if, like me, you are not particularly knowledgeable about twentieth century abstract art. For Tokyo-ites, there is not much time left, as it closes on April 17th to travel elsewhere in Japan.

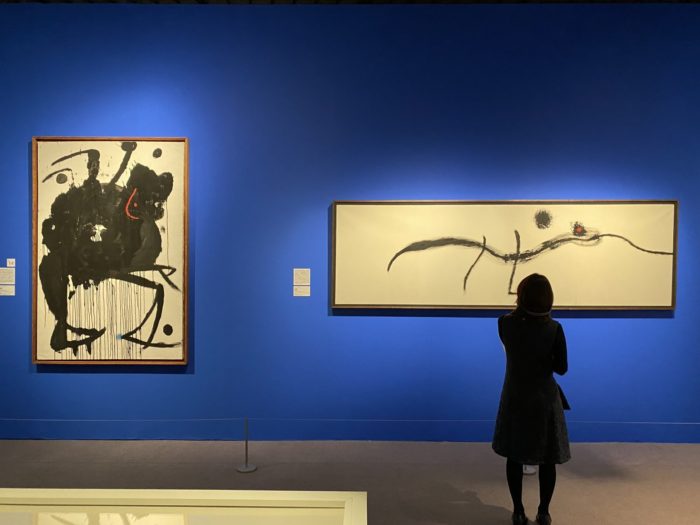

Many of the works on view, particularly the large-scale ones, have a powerful physical aura that can only be experienced by being there in front of them. Looking at an art book or, still worse, gazing at a screen could never capture it.

Especially impressive are two enormous earthenware pieces – one titled Vase, which would take three strong men to lift, and the other, Woman, which looks like a creature from another planet.

In contrast, there is the delicate painting Drop of Water on the Rose Coloured Snow, done after Miro’s first visit to Japan. Needless to say, it does not resemble a drop of water and it is unclear why the snow is rose-coloured.

There are 140 items on display and by no means all of them are interesting, but I came out with a greatly enhanced respect for Miro’s restless creativity and the depth of his engagement with Japan.

Indeed, the exhibition tells a fascinating story about the lasting status of Japan as a beacon of inspiration – and also shows how cultures can interact and cross borders even in the most difficult circumstances.

But don’t expect any polite references to wabi sabi or other familiar Japanese aesthetic values. What Miro takes from Japan is buried deep inside his highly personal, and never obvious or polite, artistic vision.

Miro is the less well known of the three great Spanish painters of the last century, the others being Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali.

A Catalan, he was born in Barcelona in 1893, at the height of Japonisme, the European boom for all things Japanese. Van Gogh had already included Japanese motifs in his paintings, and Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera The Mikado had delighted audiences all over Europe.

Then as now, Barcelona was a wealthy and highly cultured city, having hosted the World Expo five years before Miro’s birth. It had a Japanese art and craft import shop as well as several collectors of Japanese artworks that the young Miro would have known well.

The first piece in the exhibition, a 1917 portrait of his friend Ricart with a background of familiar ukiyo-e images, is the only example of standard Japonisme on view. For the rest of his long life, Miro was a dedicated and extraordinarily prolific creator of avant garde art in various forms, from paintings to pottery, collages to tapestry.

Rather than his fascination with Japan fading as the boom slipped into the past and new art movements appeared, it seemed to grow stronger with time. Possibly the most directly Japan-influenced of Miro’s works are the huge calligraphy-like black strokes he produced in the 1970s.

However abstract or surreal his work, he stuck to the principle he outlined in a 1928 interview. “Hokusai said he wanted even the tiniest point in his drawings to vibrate. And everything that lacks this life is worthless.”

Miro amassed a large collection of Japanese knick-knacks, kokeshi dolls, brushes and washi paper, books of haiku in various languages, photos of ancient haniwa clay figures. Favourite texts were Kakuzo Okakura’s Book of Tea, which had been translated into Catalan, and Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery.

Miro’s affection for Japan was reciprocated. The first time his work was shown to the Japanese public was in 1932, as part of a travelling exhibition of pieces by Paris-based avant garde artists. The first book about his work to be published anywhere in the world was written by Japanese critic and surrealist poet Shuzo Takigami in 1940.

Twenty six years later, the two men were to meet in Japan and collaborate on a poetry-painting project. Miro had been using the written word as an element in his pictures for many years, possibly influenced by the example of ukiyo-e artists.

Miro was in his early seventies when he finally visited Japan, but there had been plenty of human contact before then, direct and indirect. He had met Taro Okamoto, later to become the enfant terrible of the post-war avant garde, and other expat artists in Paris in the 1930s. In the following decades, even during the war, several Japanese artists and writers came to visit him at his rural retreat, Mont-Roig.

Two Catalan acquaintances, sculptor Eudald Serra and art fan Sels Gomis, lived in Japan from 1935 to 1948. As citizens of a neutral country, they were presumably free to move around in the wartime years. They made contact with leading figures in the mingei (folk craft) movement, which had been sparked by potters Shoji Hamada and Bernard Leach, and sent a Spanish translation of The Unknown Craftsman, an influential book written by movement leader Soetsu Yanagi, to Miro in Spain.

On their return to Barcelona, they spread their knowledge and enthusiasm about Japanese art in general and mingei in particular.

Miro had already decided to collaborate with Catalan ceramicist Josep Llorens Artigas, who became a close friend. The result was to be a further deepening in his artistic and human involvement with Japan. Artigas’ son, Joan Gardy Artigas, had been working with Miro and his father for several years when he married Mako Ishikawa, a spirited young Japanese woman who arrived in Barcelona after fleeing from her Catholic education in Japan.

The wedding, in 1962, took place in Tokyo, with the best men being potter Hamada and art critic Teiichi Hijikata. Later, Miro told an interviewer from the Mainichi Daily News “I have been interested in Japan for fifty years, but ever since Mako joined my “family”, my understanding of Japan and my affection for it has increased all the more.”

Mako and Joan Gardy Artigas are still going strong today.

In the autumn of 1966, Miro finally fulfilled his “fifty year old dream” of visiting Japan. According to Kenji Matsuda, Associate Professor at Keio University, the hectic two week trip was highly successful, with a large crowd breaking into spontaneous applause when the artist arrived at the National Museum of Modern Art.

Miro met sumo legend Taiho, viewed the Hiroshima Memorial, contemplated the Zen garden at Ryoanji and experienced many other famed sights while finding time to visit several pottery kilns and renew his acquaintance with Taro Okamoto and other Japanese artists.

At the head office of the Mainichi Shimbun, which had set up his visit, he sketched a Miro-like, which is to say unrecognizable, dedication to his host in kanji (Chinese characters).

His last night was spent at the home of Japan’s pre-eminent collector of shunga (erotic prints) where he was particularly moved by Utamaro’s Utamakura and Hokusai’s Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, featuring a naked woman enjoying the attentions of two octopuses.

Kenji Matsuda believes that he would have heard about the shunga collection from Picasso, who had known and admired those particular prints since the early years of the century.

In 1970, Miro was back in Japan again, this time providing one of the highlights of the Osaka Expo, an event still fondly remembered for showcasing Japanese creativity and open-mindedness. Together with Josep Artigas, he constructed a 5 x 10 metre ceramic wall, called Innocent Laughter.

Apparently, the Ministry of Finance refused to provide the foreign exchange necessary to fund the project unless the wall was put on permanent display within Japan – which is why is why it has resided in the National Museum of Art in Osaka ever since.

So what was it about Japan that captivated one of the great artists of modern times? After all, the vast majority of Miro’s works have nothing that is overtly Japanese about them at all.

Ricard Bru, Associate Professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, puts it this way. “Through a new Japanese gaze, precision and quest for detail and interest in what is most negligible, ephemeral and humble in nature….provided him involve and penetrate a world of details…”

Perhaps there is something else too. Avant garde art is a Western concept that defines itself through conflict with a traditional body of work, whether perspective-based representational painting or musical harmony or poetry that rhymes and has one clear meaning.

But Japan’s traditional arts were not like that at all. Noh theatre, kabuki, gagaku music, haiku, Bizen pottery, the drawings of Zen monks such as Sengai and Hakuin – these were well-established art forms, yet shocking to the Western eye and ear unused to irregularity and indeterminacy.

Japan had managed to be timelessly avant garde without knowing or caring – which is an exciting idea for creative spirits.

Joan Miro and Japan is at Bunkamura in Tokyo until April 17th, then moves to the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art from April 29th to July 3rd and then on to the Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and Design from July 16th to September 4th .