Published in Nikkei Asia 13/ 7/2022

The first thing I see on disembarking from the ferry is a giant polka-dotted pumpkin sitting on the dockside.

“That’s an iconic artwork,” says my companion, browsing the guidebook. “People come from all over the world to see it.”

“It looks more like a piece of scenery from Sesame Street.”

“At least it makes you think. That’s the whole idea.”

All it makes me think is that contemporary art is full of hype and blather. Yet, I’m willing to accept that the fault lies with me. I’ve come all the way to Naoshima, Japan’s art-island, to have my prejudices confirmed or disproved by concentrated exposure to the subject.

Naoshima is the brainchild of the late Tetsuhiko Fukutake, founder of Benesse Holdings, an education and publishing company. A man ahead of his time, Fukutake came up with the word “benesse” to signify the well-being that he wanted to promote through his business and cultural activities.

Set in the Inland Sea, the island is a twenty minute boat journey from the mainland of Okayama Prefecture. The northern part is dominated by a copper-smelter operated by Mitsubishi Materials. Turning the southern part into an art site was an extraordinarily ambitious, multi-decade project.

A bus takes us up the winding road to the isolated, super-luxury Benesse House Hotel which contains the Benesse House Museum. On its walls, I spy a Hockney and a Warhol which are pleasant, but unmemorable. More puzzling is a series of almost identical black-and-white photos of shorelines by Hiroshi Sugimoto.

“He’s interrogating the meaning of the sea,” says my companion, reading from the explanation on the wall.

“The guy went to beaches all over the world to take these photos, and they all look the same?”

“The sea is the sea.”

Unable to argue with that, I move on to the next artwork, which is “Three Chattering Men” by Jonathon Borofsky*. It consists of three tall metallic figures with jaws that go up and down while they utter the words “chatter, chatter, chatter.” From time to time, they burst into brief snatches of song.

“How annoying is that! It must drive the people who work here around the bend. No, don’t tell me. It’s supposed to be annoying, right?”

A smug nod from my companion. The next chamber is where my resistance starts to crumble. The piece, by Bruce Nauman, is a tower of neon signs that flash out an apparently random sequence of three word messages, all ending with “and live” or “and die”.

LAUGH AND DIE / SCREAM AND LIVE / EAT AND DIE / FAIL AND LIVE / PAY AND DIE

I sit in front of the display for some fifteen minutes, semi-mesmerized. The effect is like a high-speed fortune-telling device. Except these are not potential futures, but certainties. All will happen to everybody, one way or the other.

We walk along the beach towards the Lee Ufan Museum which, we are assured, is a kilometre further along the coast. Except that after walking back and forth for a considerable time we see nothing resembling a museum. What we do see is a large field with a couple of huge boulders in it.

“Are those works of art?” I muse. “Or are they just random rocks?”

“They could be both,” says my companion, unconvincingly. “Maybe it’s an open-air museum.”

We approach the rocks and study them carefully, but end up none the wiser. We are on the point of giving up when a group of art-lovers emerges from the side of a large green hillock. The hillock, it turns out, is a vegetation-covered bank behind and below which hides the bunker-like Lee Ufan Museum.

Like many of the art-related buildings on Naoshima, it was designed by the brutalist architect Tadao Ando, who was part of the art island project right from the start. Lee Ufan’s stone and steel objects do nothing for me, but the museum itself is a remarkable structure, using natural light to illuminate the exhibits.

A ten minute walk away is the Chichu Museum. Again, Ando’s building is largely underground, yet quite literally casts new light on the artworks. I found Walter de Maria’s cathedral-like installation pompous and unpleasant, but the setting of five of Monet’s waterlily paintings is the highlight of the whole Naoshima experience. There is no question that ex-boxer Ando’s creativity has significantly heightened the impact of Monet’s genius.

Next morning we take a ferry to Teshima, a larger island which suffered for decades from illegal dumping of industrial waste. Teshima Art Museum, twenty minutes from the port by electric bike, houses a single artwork – “Matrix” by artist Rei Naito and architect Ryue Nishizawa, winner of the Pritzker prize in 2010.

Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the artwork is the museum itself, including its backdrop of terraced paddies – restored for the project – drowsing in the sunshine.

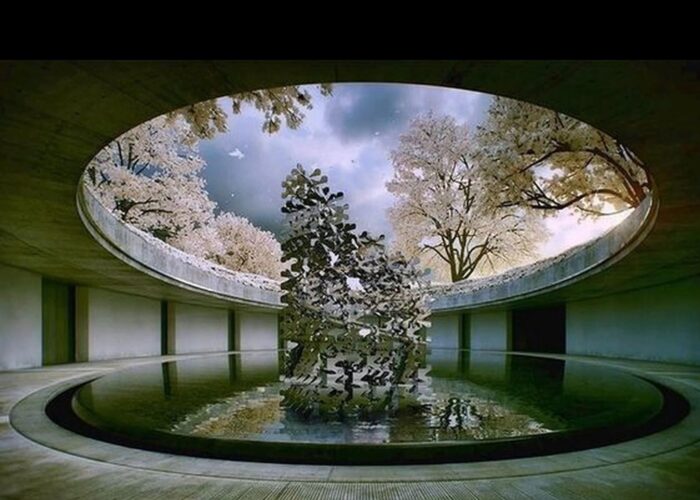

We take a looping path past the flying saucer-like café and through a grove ringing with birdsong. Then it’s shoes off to enter a giant egg-shaped structure with two large oval apertures open to the elements. Inside, there are no pillars or walls, just curved surfaces.

It takes a while to figure out what’s going on. Dribbles of water emerge from holes in the ground, scoot across the super-smooth floor, make strange shapes, merge with other dribbles to form streams and pools. It’s a slow, engrossing process

“I get it,” I whisper to my companion. “This is the primeval soup from which all life emerges.”

“Maybe so, but watch where you’re putting those big feet!”

“Damn!” It’s too late. Before I know it, I’m hopping around in a mini-lake and my socks are sodden.

“Looks like you just delayed life on earth by fifty trillion years,” my companion smirks.

What can I say but “sorry”.

We whizz down the mountain to the Yokoo House, a venerable residence of stone and charred cypress blocks that has been repurposed as a gallery. On display is the distinctive iconography of Pop Artist Tadanori Yokoo, featuring the seven gods of good luck, Yukio Mishima, pyramids, erotic woodblock prints, and pastiches of movie scenes and famous paintings.

There is also a mysterious circular tower to explore, and a bright red rock garden containing a golden stork and real carp swimming in a psychedelic pond. The effect is like wandering through one of Yokoo’s dreams.

The pamphlet praises the two toilets that Yokoo has designed for the house. Having been too busy examining artworks to attend to the usual necessities, I decide to pay a visit to a Yokoo toilet and kill two birds with one stone.

The interior is indeed glorious with lavish fittings and a throne-like seat, but no matter how hard I try, I can’t get the flush to work. Much to my mortification, I’m forced to leave behind a sizeable memento of my visit.

“You took a long time,” said my companion.

“I was interrogating the distinction between art and function.”

“At least it made you think.”

Probably the next visitor too, I reckon.

There was much else to intrigue and delight on the art island tour. To name a few favourites, there was the Tadao Ando museum, the Art House experiments in Naoshima’s Honmura district and Hiroshi Senju’s waterfall paintings at Ishibashi.

Have I been converted to the cause of contemporary art? Not entirely. I’m never going to be reconciled to that polka-dotted pumpkin, and there were other works that struck me as empty and pretentious. But I plan to be back some time for a second helping. The setting is so magical that even getting annoyed is enjoyable

Weeks later, I still hear the chattering men* going “chatter, chatter” in elevators and cafés. Sometimes I close my eyes and see neon signs flashing.

TOUCH AND LIVE / EAT AND DIE / PLAY AND LIVE / RAGE AND DIE / KISS AND LIVE

*it seems that the “Three Chattering Men” exhibit has been removed since my visit.