In 1960s Japan, there was a particular institution which acted as an incubator for the burgeoning avant garde.

The Sogetsu Art Centre was sponsored by the Sogetsu school of Ikebana (flower arrangement), which was famous for its emphasis on individual creativity. Active from 1958 to 1971, the Art Centre was set up and run by Hiroshi Teshigahara, son of the founder of Sogetsu.

Teshigahara, later to become the leader of the Ikebana school, was an unusual figure. While still a university student, he joined a clandestine unit of the Japan Communist Party tasked with violent revolutionary activity and got involved in a failed attempt to blow up the Ogouchi Dam in Okutama, north of Tokyo, in 1951. After that brush with the law, he channelled his radical impulses into artistic endeavours.

A film-maker in his own right, he has a small but highly-respected body of work to his name, including Woman in the Dunes (1962), a classic of the Japanese nouvelle vague, and Rikyu (1988), a biopic about the sixteenth century tea-master. Teshigahara was also active as a potter, set designer for opera and theatre and an innovative practitioner of Ikebana.

Woman in the Dunes – directed by Teshigahara, from a novel by Kobo Abe, with music by Toru Takemitsu. All three were associated with the Sogetsu Art Centre.

Under Teshigahara’s leadership, the SAC hosted noted foreign avant gardists such as painter Robert Rauschenberg and dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham, as well as young Japanese poets, musicians, film makers, and other artists.

Figures appearing in the annual record included modernist poet Shuntaro Tanikawa, jazzman Sadao Watanabe, graphic designer Tadanori Yokoo, film director Nagisa Oshima and butoh pioneer Tatsumi Hijikata, all destined for great prominence in their respective fields.

Terayama first appears in the SAC record in 1959, when he took part in a poetry-reading. A play he wrote was performed there in 1964, and in 1967 Terayama debuted his newly formed theatre troupe, Tenjo Sajiki, with two performances of The Hunchback of Aomori at the SAC.

In 1970, shortly before the SAC was to close permanently, he screened his best-known experimental film there, Emperor Tomato Ketchup.

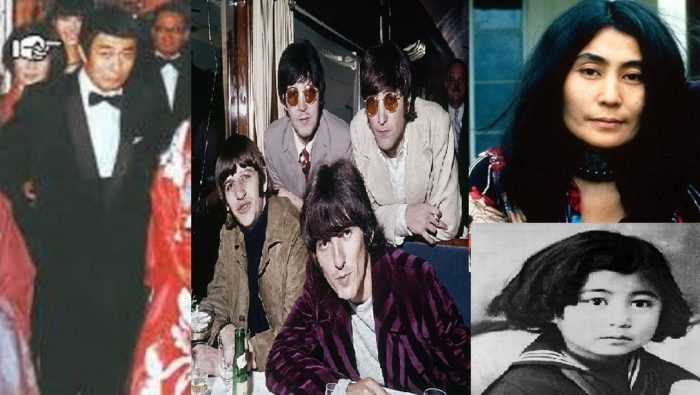

After ten years in New York, Yoko Ono returned to Japan in 1962. She naturally gravitated to the SAC, where she introduced Works of Yoko Ono, consisting of instructions for paintings, sound collages, poems and happenings. Later that year, she was on stage at SAC with John Cage, part of the series of ground-breaking concerts that produced what is known in Japan as “the John Cage shock”.

In 1964, SAC hosted the Yoko Ono Sayonara Concert, to mark her imminent departure from Japan. It included her proto-feminist performance artwork, Cut Piece. She was never to reside in her native country again.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYJ3dPwa2tI

The world of Japan’s 1960s avant garde was a small one. Terayama was on close terms with many of the SAC’s leading lights, such as poet Shuntaro Tanikawa, with whom he created Video Letter during his final illness in 1982-3. Another acquaintance was Yoko’s first husband, Toshi Ichiyanagi, who set a Terayama poem to music.

To what extent there was direct interaction with Yoko herself is unclear, but during her two year stay in Japan she and Terayama would certainly have been aware of each other’s presence and may well have viewed each other’s works.

Despite their drastically different backgrounds and artistic processes, they had several preoccupations in common. One is a macabre fascination with the children’s game Hide and Seek (see Part 4). Another is a distrust of clocks and man-made time, one of the building blocks of the modern world.

CLOCK PIECE

Steal all the clocks and watches

in the world.

Destroy them.

From Grapefruit, by Yoko Ono

A collaboration between Terayama and Yoko– in experimental film or surrealist theatre – would likely have produced fascinating results, but their personalities and artistic goals were too different to make that possible.

Indeed, whether purposely or not, these two sacred monsters of the Japanese avant garde seem not to have made mention of each others’ existence.

What we do know is that in their very different ways they both dug The Beatles.

***