Published in Nikkei Asia August 26th

This year marks both the 60th anniversary of the death of the great Japanese film director Yasujiro Ozu and the 120th anniversary of his birth. I was lucky enough to attend one of several celebratory events — a showing of two short silent films that he made in the late 1920s.

Ozu is best known outside Japan for his emotionally complex post-World War II family dramas, such as “Tokyo Story” (1953), often considered one of the greatest films ever made. The two shorts, “A Straightforward Boy” and “Fighting Friends,” were very different: slapstick comedies influenced by Laurel and Hardy.

Both films were entertaining, but the experience was immeasurably enhanced by the presence of a benshi (talker), a live performer who provides a running commentary on what is happening on the screen, giving suitable voices to the silent actors and actresses, vocalizing sound effects and sometimes interspersing ad-lib remarks about contemporary events.

I had assumed that the profession of benshi was long defunct, killed off by Al Jolson’s famous line in “The Jazz Singer,” the world’s first real talking movie: “Wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothing yet.” Those words were uttered on-screen in 1927, but nearly a century later the benshi culture is still alive and well in Japan — much smaller than in its heyday, but kept going by dedicated and highly skilled practitioners with the support of many hard core fans.

Akiko Sasaki performs to a full house; photo courtesy of Akiko Sasaki

I have subsequently watched several silent movies with benshi accompaniment. They range from Serge Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” (1925) to Harold Lloyd comedies, from “slice ‘em up” samurai epics to Georges Méliès’ bizarre “Trip to the Moon” which was made in 1902.

What is clear is that as far as Japan was concerned, Jolson was wrong. The cinematic experience had been packed with voices and sounds from the earliest years of the 20th century. Indeed, watching a silent movie without a benshi comes to feel boring, like watching a football match on TV with no commentary, no crowd noise and no referee’s whistle.

The surprising thing is not that in the silent era Japanese audiences opted to watch films with live human mediation. What is strange is that no other countries — apart from Korea, Taiwan and Thailand, all then under Japanese influence — adopted such an excellent and fun idea.

In the peak year of 1930, there were 8,000 benshi active in Japan. The most famous lived like rock stars, acquiring loyal followings, wearing fashionable clothes, stepping out with movie starlets and earning vast sums. In Tokyo, many cinemas were destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, but within a few years there were more than ever. It seemed that in the aftermath of the disaster people craved cinematic entertainment, particularly comedies such as those of Lloyd, Buster Keaton and Ozu. And crucial to the success of any cinema was the quality of the benshis on its books.

There was even a cultural divide in benshi preferences, rather like the difference in taste between those who enjoy the latest Tom Cruise movie and those who favor “Drive My Car” (2021) or “Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022).” Ordinary people, especially in the countryside, liked their benshis to be voluble and obvious. Intellectuals, like the great novelist and movie enthusiast Junichiro Tanizaki, prized restraint and ma, the Japanese sense of space.

The benshi with the most ma went by the name of Musei Tokugawa — musei means “silent” and Tokugawa is the name of the dynasty that ruled Japan as shoguns from 1603 to 1868. Tokugawa was a heavy drinker and once showed up for work too inebriated to utter a word. Even so, his sophisticated fans praised the subtly of his performance.

Inevitably, the coming of the talkies had a powerful effect on Japan’s cinema culture, dealing a shattering blow to the benshis. Many quit and reinvented themselves as writers, comic story tellers or voice actors. Others simply faded away. One of the saddest stories concerned a successful benshi known as Teimei Suda, who had a senior position in a committee set up to resist the firing of the many unneeded benshis. Failing in the impossible task of reversing history, he fell into a depression and in 1933 took his own life in a double suicide pact with a girlfriend.

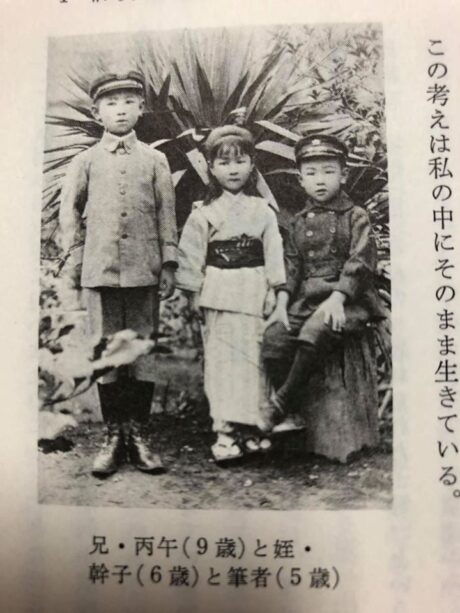

Heigo at 9 (l), Akira at 5 (r)

That young man, dead at the age of 27, is better known as Heigo Kurosawa, elder brother of the great director Akira Kurosawa. Heigo had been a brilliant student at school and the family expected much of him. It was only after his death that his less promising younger brother was forced to find a regular job to support the family finances. Fortunately for all of us, he chose a chemical company that had recently diversified into filmmaking.

In Japan, silent films did not disappear overnight. For technical and financial reasons, the studios continued to make them until 1938. After the devastation of the war, some benshis traveled the countryside providing badly needed entertainment at a time when conventional films were in short supply. One was Shunsui Matsuda, son of a well-known benshi, who had got his own start as a child performer in the golden age.

Back then, nearly all benshis were male. In today’s world, the gender split is more equal. The most experienced contemporary practitioner working is Midori Sawato, a female benshi who has been in the business for over 50 years and studied under Matsuda, who died in 1987. So, as with many Japanese arts, there is an unbroken line of succession from the early years of film to today.

The recipient of several awards, Sawato breathed life into the two Ozu shorts I saw earlier in the year. She has performed overseas, and also advised on the period comedy-drama “Talking the Pictures” (2019), directed by Masayuki Suo, which tells the tale of a rascally fake benshi.

A scene from “Talking the Pictures”

A new generation has since taken up the challenge. Akiko Sasaki is a leading light of today’s benshi scene, and also has an impressive depth of historical knowledge about the subject. Much of the information in this article comes from her.

What caused her to become a benshi? Her first career was as a TV anchor and roving reporter. By chance, a friend took her to see a performance by Sawato and she was immediately enthralled. “I knew it was my destiny,” she says. What hooked her in particular was “the sense of oneness” between the film, the benshi, the musical accompanist and the audience.

Sasaki ascribes the longevity of the benshi culture to its similarity to traditional Japanese “talking arts” such as rakugo comic story-telling and, in particular, bunraku puppet theatre. Like the stars of the silent movies, the dumb wooden puppets need outside agency to give them speech.

To accentuate that sense of lineage, Sasaki uses five and seven syllable lines, the foundational rhythm of haiku and 0ther traditional poetic forms, when performing with Japanese silent movies. Given that benshis are expected to synchronize their words when close-ups of mouthed speech appear on the screen, that makes for an extremely complex task.

Working in the dark; photo courtesy of Akiko Sasaki

Each benshi writes his or her own script. According to Sasaki, a script should not simply explain the action and provide some dialogue but “open up the story” in the manner of a skilled playwright. She tells me that she has written some 220 scripts and gives 80 to 100 performances a year in music venues, libraries, schools and art-house cinemas such as Bacchus in the Koenji area of Tokyo. She also conducts classes for aspiring benshis of all ages, from school children to retirees.

Interestingly, Sasaki’s favorite silent film is Ozu’s “I Was Born But…”, a 1932 comedy with a dark message about class and human nature. Ozu made the very similar film, “Ohayo” in 1959 with the benefit of colour as well as actor’s voices. Despite that, the film is nothing like as good as the original, with its emotional cruelty and shocking physical struggle between the father and his adolescent son. Without a doubt, the best solution would be to watch the 1932 version with benshi accompaniment.

How would you set about becoming a benshi today? A good start would be to attend the performances of professionals like Sasaki. If you have the requisite verbal fluency, script-writing skill and sheer dedication, you might have a chance to try your luck. Ultimately, though, as with stand-up comedians, you either have the talent or you don’t. The customer is king.

In order to enjoy a modern-day benshi performance, it helps to have some Japanese language capability, but even without it the experience is worthwhile. Perhaps one day, some talented bilingual person will perform as a benshi in English. Or perhaps an AI benshi will get there first.

Whatever happens, Japan’s unique silent film culture has already lasted four times as long as silent movies did in the rest of the world and is likely to continue for a long time to come.