Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 12/6/2019

An unusual exhibition has just opened in the hallowed chambers of London’s British Museum, one dedicated to Japanese manga. The fact that it is taking place is a tacit acknowledgement of the genre’s emergence as a respected art form and officially sanctioned emblem of Japanese “soft power.”

Wandering through the exhibits, I couldn’t help but be reminded of “Sturgeon’s Law” — the American science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon’s dictum that 90% of everything is trash. That certainly goes for manga, which is often infantile, vulgar and banal.

Not long ago, it would have been shocking to see what was widely regarded as pop culture effluvia being displayed in proximity to the Elgin Marbles, from the 5th century B.C., and other treasures of antiquity. Most of the huge annual output of manga publications is consumed like instant ramen, then pulped and forgotten. According to the translator and writer Frederik L. Schodt, the doyen of non-Japanese manga experts, a manga book of 320 pages would be read in about 20 minutes.

The selection at the British Museum includes some cloyingly twee anime and those annoying Pokemon creatures. On the other hand, there are some extraordinary pieces on view, such as a vast kabuki curtain daubed with a motley crew of comical and scary monsters. Kyosai Kawanabe, working in 1880, apparently knocked the whole thing off in a four-hour sake-fueled creative frenzy. You can’t get more rock ‘n’ roll than that.

It is also interesting to see the originals of Tetsuya Chiba’s Ashita no Jo (“Joe of Tomorrow”) series about a heroic boxer from the wrong side of the tracks. Such was its impact in the late 1960s that Shuji Terayama — a poet, film director and all-round provocateur — presided over a mock funeral for Jo’s rival, who died in the ring. Seven hundred mourners lined up to pay their respects as incense swirled and a Buddhist priest intoned sutras.

Manga has become internationally respected as an art form because of its inherent trashiness, not in spite of it. That is the other side of the genre’s dynamism and spirit of innovation. As Schodt writes in Dreamland Japan: Writing on Modern Manga, the barriers to entry are low compared to most other forms of entertainment.

To get started, all you need are pencils and paper. You don’t even have to draw all that well. That punk-like do-it-yourself ethos guarantees a massive field of entrants and a Darwinian race for survival, where only the most popular creations triumph. Of these, only a tiny percentage will achieve the status of classics and be remembered for decades to come.

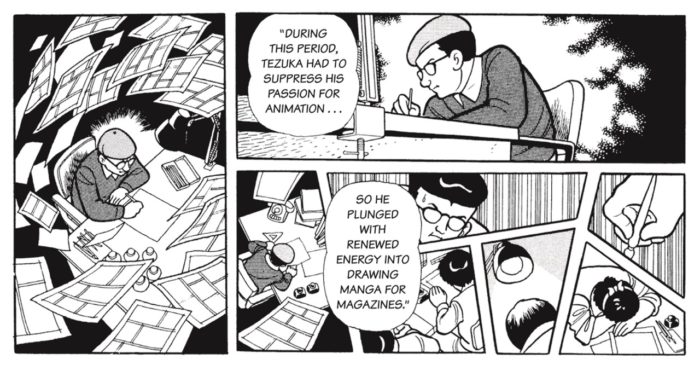

In the exhibition catalogue, manga creator Go Ito describes the genre as “sordid, attractive, simple and compelling.” All that is true, but there is more. As with cinema, which it resembles in its emphasis on visual story-telling, manga has offered some extraordinary talents the opportunity to express themselves. The prime example is Osamu Tezuka, sometimes misleadingly called “the Walt Disney of Japan,” but known in Japan as “the God of Manga.”

It is Tezuka who is usually credited with inventing the cinematic techniques which distinguish manga from Marvel-type comics. Schodt explains how these techniques enable manga artists to develop psychological and emotional depth.

“Like good film directors, they can focus reader attention on the minutiae of everyday life — on scenes of leaves falling from a tree, or steam rising from a bowl of hot noodles, or even the pregnant pauses in a conversation — and evoke associations and emotions that are deeply moving.”

Tezuka is best known in the West for entertaining works such as Atom Boy and Kimba the White Lion. However, in the 1970s he created several disturbing masterpieces that explore the darkest recesses of human nature. Fortunately, Ode to Kirihito, MW, Ayako, The Human Insect, Apollo’s Song and Message to Adolf are now available in English, as are his two long-running philosophical series, Phoenix and Buddha, which deal with reincarnation, the future of humanity and the oneness of all things.

Tezuka stands in relation to Japanese manga rather as Akira Kurosawa does to Japanese film. In fact the Emperor of Japanese Cinema and the God of Manga had much in common. They were both known for their “humanistic” works, in which there are no outright heroes and villains, but flawed individuals struggling with the good and evil within themselves.

In an indirect compliment to their originality, both were plagiarized by foreign copycats — Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) was remade by Sergio Leone as For a Few Dollars More and Tezuka’s Kimba inspired Disney’s The Lion King. Both men admired the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky and tried their hands at adapting him — Kurosawa with The Idiot, Tezuka with a children’s version of Crime and Punishment.

Not much is known about their personal relations, but Kurosawa owned Tezuka’s collected works and asked him to be artistic director on a film project — an adaptation of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Mask of the Red Death — that never got off the ground.

Sturgeon’s Law was intended as a defence of science fiction against high-brow critics who were convinced of the genre’s total worthlessness. The defence is as valid for manga as it is for novels, films, paintings and so on. Ninety percent may be trash, but the remaining ten percent includes profound and challenging works to amaze, delight and shape future generations.