Published in Japan Forward 06/02/2022

Apa Hotel (Always Pleasant Amenities) is an impressive outfit. Its tally of over 100,000 rentable rooms makes it by far Japan’s largest hotel chain. Female CEO Fumiko Motoya often appears on TV and is well known for her right-wing views and spectacular hats.

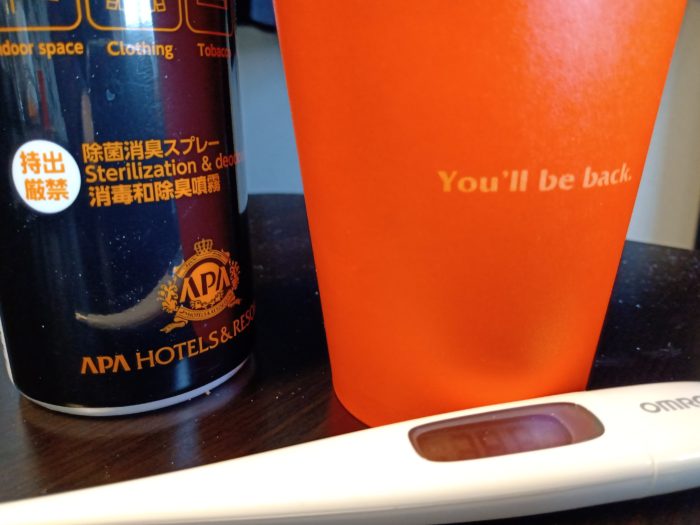

I write these words from the Apa Yokohama Bay Tower which has 2,300 rooms. Mine is tiny – just 11 square metres – but the use of space is highly efficient and the tech is first class.

In normal times, I would recommend it to anyone wanting a cheap, comfy base for a few days of sight-seeing or business activities in the area, especially as it boasts a large hot-spring bath, a gym and several restaurants.

Unfortunately, these are not normal times and I will not be making use of the excellent facilities. Like all the other “guests” of this otherwise empty hotel, I was brought here on a bus from nearby Haneda Airport and am to be confined to my room for six days. We are undergoing quarantine, a much stricter version than the sensible “isolate at home” type I experienced when entering Japan last October.

So what’s the new regime like? First and foremost, alcohol is banned. Fresh air and direct sunlight, those other great remedies for jetlag, are also unavailable as the windows are sealed. Exercise is out of the question. You either sit at the desk or lie on the bed or squat in the bathtub. There are no other possibilities.

As for food, it must be at room temperature like the cold bentos (lunch boxes) that we collect – fully masked, of course – from our outside door-knobs three times a day. You can order a delivery meal, but explicitly forbidden are pizza, ramen, gyudon, sandwiches, sushi, and other hot or chilled foods.

Don’t bother trying to smuggle in a bottle of champagne and a cordon bleu meal. A notice warns that all deliveries will be checked by quarantine officers stationed at the hotel, a process that “may take several hours”.

Regular announcements emanate from a loudspeaker in the ceiling. A knock on the door at 6.50 a.m. informs me that it is time to spit into a plastic tube and hand it to a quarantine officer dressed in hazmat gear.

The A.I. app installed on my phone at the airport springs to life five times a day, making sure that I haven’t escaped and gone kayaking in the bay or bar-hopping in the funky Noge district. If I’m lucky, I may get a call from a real human being enquiring about my body temperature.

At one point, I managed to lock myself out late at night while depositing an empty bento box. With the elevators refusing to go all the way down to reception, I found myself wandering from empty floor to empty floor, like the hero of Haruki Murakami’s surreal Dance, Dance, Dance. Luckily, I bumped into a lone security guard who arranged a spare key for me.

I don’t want to pretend that all this constitutes some sort of cruel imposition. The quarantine staff at the hotel are unfailingly patient and helpful. The bentos are of convenience store quality, though the mostly fried and processed food would be greatly improved by a few beers to wash it down.

The same goes for the entry procedures at Haneda. The supplementary staff – mostly female, including many of non-Japanese origin – are doing a good job under pressure, but the system in which they operate is exceedingly slow and cumbersome.

Providing printouts of documents on smart phones proved especially challenging, given my rudimentary IT skills and a shaky performance by the airport wi-fi. There was also a problem with my saliva, which is apparently of poor quality and took an unusually long time to analyse.

When I finally stepped into the bus that would take me to the Apa Hotel, I experienced a hot wave of guilt. All the quarantine-bound travellers inside had been patiently waiting for me – including a Japanese woman in her early twenties who had come all the way from Texas with a one year old baby.

Altogether, it took four hours to get from touchdown in Haneda to the arrivals hall, with another hour of processing awaiting in the basement of the Apa Hotel.

Needless to say, most other countries have imposed much harsher restrictions. Hong Kong mandates a three week hotel quarantine and, unlike Japan’s, you have to pay the bill yourself. In December, President Macron suddenly banned all British citizens from entering France.

Australia and New Zealand have been amongst the most draconian countries, preventing their own citizens from returning home for well over a year. If the Australian Open tennis tournament had taken place in Japan, Novak Djokovic would probably now be basking in the status of “GOAT” (“Greatest Of All Time”) instead of being unceremoniously thrown out of the country before having a chance to compete. Djokovic’s sin: to refuse vaccination.

Japan has taken a much less authoritarian view. At no point in the journey from north London to Yokohama was I asked to show my vaccination certificate.

In the global context, claims that Japan is reverting to sakoku (closing the country, as from 1639 to1854) are absurd, especially when some of the same voices were calling for the Tokyo Olympics to be cancelled just eight months ago. Nor is Japan alone in hiking the severity of restrictions at a time when actual harm is declining. Many European countries have continued to tighten, although confirmed Covid deaths in the EU are running at half the level of this time last year. So far only Denmark has felt confident enough to return to the pre-Covid regulatory regime.

The peculiarity of Japan’s situation is that it is clearly one of the winners of the Covid era. Amongst the populous, highly developed countries, it has by far the lowest rate of confirmed Covid deaths and excess mortality, as calculated by the The Economist magazine’s machine learning system. This it has achieved without compulsory lockdowns, penalizing the unvaccinated and other illiberal measures that have been widely adopted elsewhere.

Japan’s common sense approach was working perfectly well, so why change it now? After all, it is generally recognized that the Omicron variant is highly infectious but very mild. Harsher entry procedures will accomplish nothing.

The answer, it seems, is politics. Specifically, former Prime Minister Suga saw his approval ratings tank to the extent that he had to resign after a mini-surge in Covid infections last summer. In reality, there was nothing wrong with Suga’s approach and the surge had disappeared by the time his successor took over. Nevertheless, the political lesson was clear. Looking tough and decisive played well with the public. Being pragmatic cost Suga dearly.

Judging from the recent Covid statistics, this highly disproportionate “water’s edge” policy has already failed, as was bound to happen. Obvious policy failure is rarely popular with the public, so political logic suggests a change too.

Given its stellar record in coping with previous, much more deadly strains, Japan should be a world leader in “living with Covid”, up there with Denmark. It still can be.