Between 1960 and 1962, Shuji Terayama and film director Masahiro Shinoda collaborated on four films produced by the Shochiku studio.

When the first, Dry Lake, was made, Shinoda was 29 years old and Terayama, then mainly known as a tanka poet, just 25. Their creative peaks lay many years in the future, but these early works offer an intriguing glimpse of what was to come.

Two of the films – Dry Lake and Tears on the Lion’s Mane – were part of the Shochiku “nouvelle vague” programme, designed to fit in with the rebellious youth culture of the day, yet the Terayama-Shinoda duo imbued them with a twisted, ironic sensibility unusual for the genre.

The other two films are a bizarre musical comedy (My Face Red in the Sunset) about a group of hitmen, and a romantic melodrama (Epitaph for Love) which is probably the straightest film Terayama was ever involved in.

All four were filmed in Yokohama and its environs. All present contrasts between troubled youth and a corrupt adult world controlled by creepy politicians and ruthless businessmen. All feature sexual relationships between young men and much older, somewhat predatory women, who are bored with their unattractive or impotent husbands / partners. Terayama, with his mother complex, would have found this theme right up his street.

The young Shima Iwashita – who was to marry Shinoda in 1966 – stars in three of the films, projecting a demure image far from the voluptuous maturity of her later career. Likewise appearing in three films is a well-groomed collie that symbolizes the decadence of the rich.

All the films use music creatively, with jazz, pop and rockabilly signifying youthful energy and authenticity, while the pretentious wealthy classes favour Western classical music. The song lyrics – in Tears on the Lion’s Mane and My Face Red in the Sunset – are characteristically Terayama-esque.

DRY LAKE (English title: Fury of Youth)

1960, Screenplay by Terayama, adapted from a novel by Eiji Shinba. Terayama also has a cameo appearance in the role of a student activist. Eiko Kujo, who he was later to marry, plays one of the fun-loving female students.

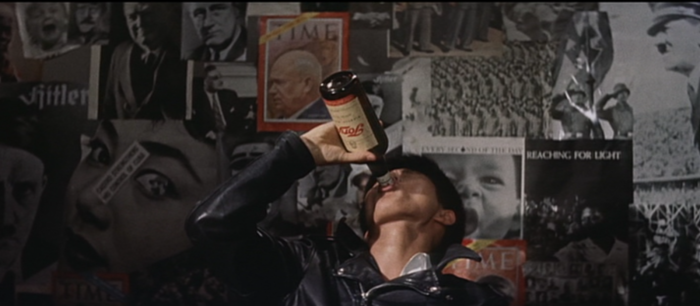

As is often the case, the Japanese title – with its implication of emptiness and sterility – is more apposite than the English version. The story brings together three strands of contemporary youth culture – the bratty taiyo-zoku (“sun-tribe”) with their yachts and home-made blue movies, the student radicals with their anti-American street protests and the leather-jacketed, nihilistic loner.

It is clearly the latter character that holds Terayama’s interest, to the extent that he gives him some Teramaya-esque attributes. Just like the writer of the screenplay, the hero was born in remote Aomori Prefecture, enjoys concocting fictional accounts of his life and admires Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes.

Our hero is disengaged, transgressive and filled with a restless energy that makes him dangerous – again, rather like his creator. On the wall of his room are cuttings of movie actresses in bikinis, but also of Fidel Castro, Roosevelt, Trotsky, Chiang Kai Shek, Hitler and Mussolini. It is the charisma of strong leaders that attracts him, not their ideas.

The earnest leftist students are shocked by his impulsive behaviour. After resigning from their organization, he questions their pacifist idealism.

“What would happen if America stopped its economic support?” he objects. “Can you guarantee people’s livelihoods when that happens? Our productive capacity may have increased, but how can resource-less Japan carry on with no support?”

But neither does he have any time for the sleazy conservative politician with whom he is sharing a lover.

Dry Lake was released just months after the anti-security riots portrayed in the film’s climax. There are a moments that seem remarkably prescient.

“When we see men in fancy cars or going golfing with their young women, we want to kill them or be like them. It has to be one of those two.”

That was more or less the future of the Japanese student movement. By the mid-1970s, a small contingent of extremists has moved on to terrorism and murder, but the overwhelming majority were ready to play golf.

To be continued…