Published in Japan Forward 21/01/ 2022

It was thanks to Covid that I recently managed to view the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at the Tate Modern in London.

The event, which opened in the summer of 2021, had been fully booked until the closing date in March 2022. With the Omicron variant ripping through the British population, persistent telephoning was finally rewarded. There had been a cancellation and a mid-afternoon slot was available.

I’m neither knowledgeable about contemporary art nor particularly enthusiastic. What fascinates me is the Kusama phenomenon itself. How did a ninety two year old woman who has been a virtual recluse in a Tokyo mental hospital since 1975 become “the world’s most popular artist”.

That accolade was bestowed on her by The Art Newspaper in 2014 – and rightly so. Her Infinite Obsession retrospective in South and Central America attracted an exhibition attendance of over two million people.

If anything, her stock has risen even higher since. In 2016, Time Magazine chose her as one of the 100 most influential people in the world, alongside Barack Obama, Usain Bolt and Caitlin Jenner.

On a freezing cold day in November 2017, five thousand New Yorkers lined up for several hours to enter two of her “Infinity Rooms” (mirrored spaces illuminated with various light sources). The time given each person to experience each box was thirty seconds. Likewise, the wait time was several hours for All the Eternal Love I Have For The Pumpkins, her 2016 exhibition in London.

At the Tate this January, probably thanks to Covid again, reservations have taken the place of queuing around the block. That is not to say I didn’t have to wait in line. About three quarters of my allotted one hour was spent waiting to be admitted to the glittery darkness of the Infinity Rooms, which are just about large enough to accommodate four people at a time.

Londoners did get a better deal than New Yorkers, though. We were allowed a full two minutes inside the rooms, which were titled Chandelier of Grief and Infinity Mirrored Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Life.

According to the Tate, these were “exemplary of Kusama’s practice as a persistent enquiry into the phenomenological potential of art.”

To my inexpert eye, the Infinity Mirrored Room looked more like a 1970s disco, while the other room was similar to a “hall of mirrors” attraction at a funfair. Indeed, some of my fellow viewers had brought their young children who seemed to be having a great time. Literally everyone was taking selfies, including the kids.

In some exhibitions, snapping pictures is not allowed. Here it was encouraged. In fact, you could say it was the main point. Thinking deep metaphysical thoughts was out of the question, despite the cosmic message from Kusama inscribed on a gallery wall.

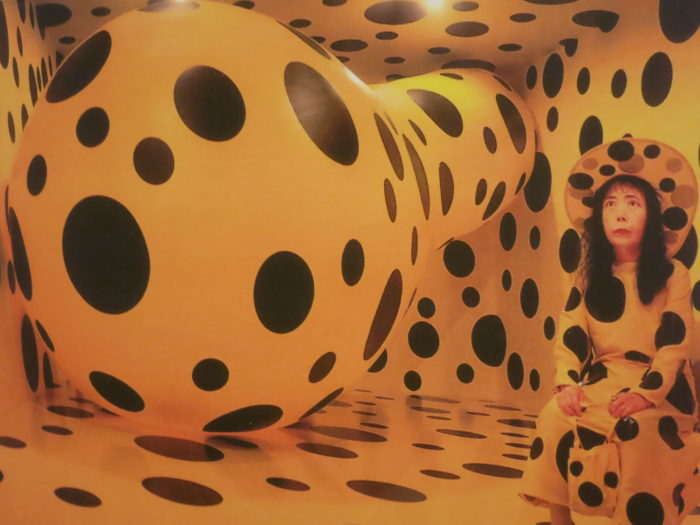

Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars …when we obliterate nature and our bodies with polka dots, we become part of the unity of our environment.

I wasn’t the only one to be underwhelmed by the experience. Adrian Searle, art critic of The Guardian, wrote that the installation reminded him of his “cheapo garden fairy lights”. Another critic from The Guardian, Jonathan Jones, described her work in harsher terms: “as fun as a fizzy drink and about as nourishing”.

And yet Kusama was a formidable presence in her New York heyday of the late fifties and sixties. That much was apparent from the photos and film footage also on display in the exhibition.

In those days, her main theme was sexuality. Multiple male organs constructed from clay or cloth adorned the various installations and objets she created.

Like Yoko Ono, who appeared in New York avant garde circles at roughly the same time, she was a natural-born provocateur with an endless supply of chutzpah. She staged orgies and a gay wedding in her studio, stripped naked in anti-war demonstrations and painted the bodies of her friends with polka dots.

In an open letter to President Richard Nixon, she promised to “lovingly, soothingly adorn your hard masculine body” if he would only agree to “make this world a new Garden of Eden”.

Some of the conventional works were impressive too, particularly the large scale “Infinity Net” series of abstract paintings which she started in 1959.

Kusama the transgressional outsider was a lot more interesting than Kusama the global brand. Her outrageous “happenings” were more entertaining than her pretentiously titled Infinity Rooms; her phallus-encrusted boat from 1963 more memorable than the enormous polka-dotted pumpkins that have rolled off her production line in recent years.

At some stage, the art of the deal took over from the art of the heart.

Perhaps that was inevitable. Like Andy Warhol, Kusama never saw artworks as holy creations separate from ordinary reality. At the Venice Biennale in 1966, she exhibited an installation of mirror balls without being invited and then sold them off for two dollars a pop. “Why can’t I sell art like hotdogs or ice cream,” she declared. Now she sells packs of two souvenir mugs for £52 at the Tate and signs up to a collaboration with Louis Vuitton.

In the early years of this century, Kusama’s work was handled overseas by the Gagosian Gallery whose proprietor, Larry Gagosian, was described by Forbes magazine as “the P.T. Barnum of the art world.” In 2013, she switched to the rival mega-gallery of David Zwirner. Between them, they have powered Kusama to extraordinary commercial success. In 2009, her works grossed $ 9.3 million at auction. In 2019, they grossed $98 million.

No amount of “eternal love” could save this pumpkin from a 2021 typhoon

It is no coincidence that 2009 also marked the start of the era of unconventional monetary policy, by which central banks drove down interest rates to unprecedentedly low and even negative levels. Elevating asset prices was an explicit policy goal, successfully achieved as prime real estate, tech stocks, crypto currencies and collectables such as art took off for the stratosphere.

Put together the additional wealth that has accrued to the super-rich and the selfie-friendly appeal of Kusama’s recent productions and you have the background to her rise to superstar status. But you need something else too, an ability to satisfy a widespread yearning as transmitted by the herd mind of the internet.

Adrian Searle of The Guardian explains it like this – “Many people are hungry, I suppose, for some kind of transformative, mystical or even transcendental experience, and one that requires neither fasting nor drugs, let alone months or years of mental and physical preparation.”

In other words, it is secular religion. All you need to join the congregation is a cell phone and the willingness to stand in line for a few hours. The Deity of course never appears in person, as is usually the case with deities.

Kusama remains extremely prolific. “I want to paint 1,000 and 2,000 paintings,” she says. “I want to keep painting even after I die.” That is quite possible since her team of Japanese fabricators can create new product from her ideas and her dealers will certainly be happy to sell it.

On the day of my visit, the other galleries in the Tate were as silent as a morgue. On the way out, I asked one of the staff why Kusama was so uniquely popular. He answered with a laconic shrug and a single word. “Instagram.”

Meanwhile, the Infinity Mirror Rooms exhibition at the Tate Modern has been extended until June 12th 2022. For hardcore fans, there is an evening viewing that includes a £75 dinner.

Pumpkin pie is not on the menu.