Published in Nikkei Asia 18 May 2024

Sadao Watanabe is a monumental figure in the world of Japanese music. His life story, rich in often self-deprecating anecdotes, is fascinating, even for those who have little interest in jazz. The tale it tells, of resilience, positive energy and total commitment, is also the tale of post-war Japan.

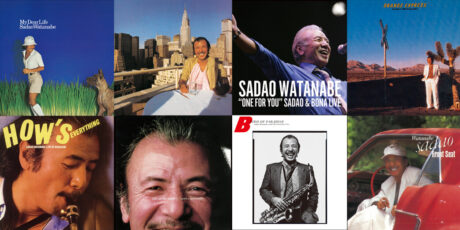

In album covers from the early 1960s to the 21st century, the saxophonist is often shown with a joyous smile on his face. It is there today as we discuss his latest release, making a total of about 80 since his recording debut in 1962. At the age of 91, he is spry and affable and brims with enthusiasm as he prepares for an eight-date tour of regional Japanese cities.

A self-taught musician, Watanabe got his start playing dance music for the American occupation forces after World War II and went on to explore many other genres, from Charlie Parker-style bebop to 1980s fusion, from African music to the work of classical composer Pierre Max Dubois.

The first jazz musician to be awarded the prestigious Order of the Rising Sun by the Japanese emperor, he has seen huge commercial success. In 1980 he managed the feat, extraordinary in the world of jazz, of selling out the 30,000 capacity Budokan arena for three consecutive nights.

He has also collaborated with many heavy hitters from overseas, such as pianist Chick Corea, saxophonist Michael Brecker and Tony Williams, the drummer in Miles Davis’ second great quintet.

The new album is a collection of ballads. Nabe-Sada, as he is affectionally known, was never a politically engaged musician, but the choice of the title track — “Peace” by Horace Silver– was, he tells me, a reflection of current events. “If I Could,” one of the three original numbers on the album, is dedicated to the Tibetan people. Watanabe visited Tibet in 1996 and credits the experience of playing for children in the street there with reviving his appreciation of the basics of music.

Watanabe has had a long relationship with Brazilian music, which he was responsible for introducing to Japan in the mid-1960s, so it is no surprise to find a delicate piece by Antonio Carlos Jobim on the record. Other numbers include “Deep in a Dream,” closely associated with Chet Baker, and “I’m a Fool to Want You,” which was partly written by Frank Sinatra during his troubled relationship with Ava Gardner.

Watanabe with Brazilian friends

The format is a classic quartet, led by Watanabe’s spare, unhurried alto sax. It features drummer Ittetsu Takemura, who is almost 60 years younger than the leader, as well as experienced Americans Russell Ferrante and Ben Williams on piano and bass, respectively. Why the emphasis on ballads? I ask.

“I had wanted to make an album of ballads for a long time. I like Frank Sinatra’s ballad album “In the Wee Small Hours,” and there was a time when my wife and I used to play it when we went to bed. I still play this album as background music whenever someone comes over to my house”

Watanabe was born in 1933, as were Yoko Ono and retired Japanese Emperor Emeritus Akihito. It was the year in which “King Kong” was wowing cinema audiences and Japan walked out of the League of Nations, putting itself on a collision course with the U.S. and the U.K.

Watanabe’s father ran an electrical shop in Utsunomiya, then a rural town north of Tokyo, but had previously been a professional player of the satsuma lute. According to his son, the music it made was highly rhythmic and had a distinct “swing.”

In one of the contradictions of the era, Watanabe senior was also an admirer of the military spirit, and the boy who would devote his life to to the improvisational freedom of jazz was named after the Japanese general Sadao Araki, who was later imprisoned as a war criminal.

There must have been something special in the water of pre-war Utsunomiya. Watanabe’s late brother was a jazz drummer, and his sister is Chiko Honda, a well-known jazz singer who is also the mother of Tamaya Honda, one of the most explosive drummers on the Tokyo scene.

In the final phase of World War II, two-thirds of the market town was destroyed in a 100-plane bombing raid. From an air-raid shelter, young Watanabe watched the electrical goods store which doubled as his home go up in flames.

One of the few possessions he had brought with him was a harmonica, given to him by his father. He played it in the rice fields as the family moved to the farming areas in search of food. When Japan’s surrender was announced, his overwhelming emotion was relief.

There had always been music in his world — the sound of violins, pianos and accordions — but the life-changing epiphany came when a friend whose father ran a cinema took him to see a Bing Crosby movie called “Birth of the Blues.” The hero, initially shown as a young boy of roughly Watanabe’s age at the time, is a brilliant clarinettist who neglects his classical lessons in favor of playing jazz with black musicians in Bourbon Street dives, much to his father’s displeasure.

Watanabe’s own father was not much happier when his son set his heart on becoming a clarinet player — which would require the purchase of a clarinet. Such an expenditure was out of the question in Watanabe senior’s view, but Watanabe junior proved his determination by going on hunger strike, and in the end a second-hand instrument was procured.

In a glimpse of the devotion to practice for which he became famous, Watanabe clambered onto the roof of his house and played there for hours. Many decades later he would rehearse the complex scores of Dubois in a bullet train toilet.

Young Sadao; already a musician in his high-school years

Jazz boomed during the 1945-1952 American occupation of Japan, offering plenty of opportunities to keen young musicians. For lucrative gigs entertaining American officers, an A to D ranking system was employed, with the best bands commanding the highest remuneration. Needing a favorable verdict from the jazz critic who made the ranking decisions, Watanabe’s group of hopefuls treated him to a dinner of broiled eel. Their reward was a new grade created especially for them: E. Their egos were bruised, but they were in.

Graduating from clarinet to alto sax, Watanabe moved to Tokyo and his playing improved dramatically. He had promised his father that he would return to the family business if he could not support himself as a musician within two years. But soon he was earning twice as much as the average office worker. On one occasion, the 18-year-old had so much cash on him that the police pulled him in as a robbery suspect.

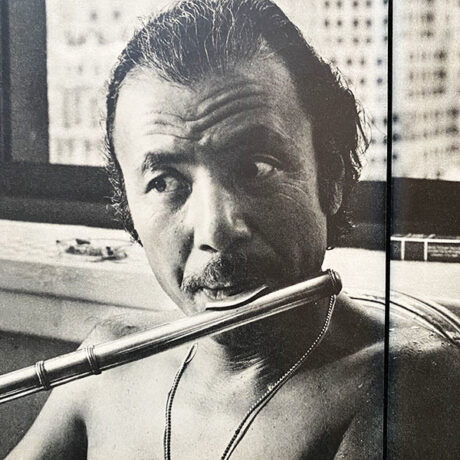

Typical of his drive was his decision to take up the flute, joining a class run by a prominent classical player who was a strict disciplinarian. Happening to hear him playing on the radio, she made him promise never to play the flute in public again unless he could produce an acceptable sound. Watanabe responded by practicing eight hours a day, and his flute would be showcased to great effect in his African- and Brazilian-inspired albums of the 1960s and 1970s.

Watanabe on flute

By the mid-1950s, the U.S. was drawing down its military presence in Japan, which meant recession for the jazz economy. At the time, Watanabe was a member of Toshiko Akiyoshi’s band, the best in Japan. The star jazz pianist and composer was a forceful leader and had become his mentor, exposing him to new ideas and requiring him to improve his shaky sight-reading skills.

Having been discovered by Oscar Peterson playing in a Ginza club, Akiyoshi headed for the Berklee School of Music in Boston and has spent most of her subsequent life in America.

Watanabe took over the band in 1956, but life was tough. He had married and he and his wife had frequent recourse to the services of pawnbrokers. Joining a crowd-pleasing jazz quartet called The Big Four as a guest musician, he went on tour and witnessed a dramatic event in a tough part of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands. In a gangland dispute about the takings, the promoter was shot dead at the climax of the drummer’s solo, and the band had to be hustled out of town.

At this crucial juncture in his career, his old mentor Akiyoshi came to him with some advice. Why not follow in her footsteps and study at Berklee? It would mean being away from his family for a lengthy stint — by then the couple had a daughter — but his wife was supportive.

Watanabe in the Toshiko Akiyoshi quartet in the mid-50s.

In 1962, Watanabe left Japan on his first overseas trip. On his first night in New York, Akiyoshi took him to the Five Spot club, and he was called to the bandstand to play with the Charles Mingus group, one of the most brilliant formations of the era.

Watanabe combined study at Berklee with a key role in the popular Gary McFarland band, which was riding the bossa nova boom. But unlike Akiyoshi he had no intention of basing his musical activity in the U.S. He learnt a lot there, in terms of composition, improvisation and harmony, but there was another lesson that was to prove important to the future of Japanese jazz.

As he put it on his return to Japan, “Going to America enabled me to have the confidence that what I was doing in Japan before was not a mistake.”

Shucking off the inferiority complex was a radical move. At the tine, it was taken for granted, by both Japanese and foreign critics, that Japanese jazz was a poor quality imitation of the real thing.

That was part of a broader seam of condescending cultural judgements such as “the Japanese have no creativity” etc, as highlighted in Endymion Wilkinson’s 1980 book “Japan Versus the West: Image and Reality.”

Watanabe was living proof that it did not have to be that way. For a while, he more or less was Japanese jazz

E. Taylor Atkins, author of “Blue Nippon” (2001), a history of jazz in Japan, put it like this: “Watanabe found an eager audience that practically begged for his leadership, and he did not disappoint them… It would be difficult to discount [his] high-profile campaign to resuscitate his nation’s interest in jazz; he energized Japan’s lethargic jazz community, bridged its generation gaps, piqued the interest of jazz fans young and old and inspired musicians to develop their talents.”

As it happens, a new generation of adventurous and highly skilled musicians was arriving on the scene, several of whom got their grounding in his new group, such as guitarist Yoshiaki Masuo, who was later to spend several years with Sonny Rollins, and cerebral pianist Masabumi Kikuchi.

Watanabe with Kikuchi, Masuo, tenor sax player Mine and others destined to have illustrious careers

Such was Watanabe’s cachet that he was able to take his young colleagues to perform at major overseas festivals such as those in Montreux and Newport, in the U.S. state of Rhode Island.

Figures from Japan’s nascent avant garde, such as guitarist “Jojo” Takanayagi, appeared on his albums too. The tradition of encouraging new talent continues today, with drummer Takemura having joined Watanabe’s band in 2010 at the age of 20.

Apart from his own music, Watanabe has been a tireless educator and booster of Japanese jazz. Taking a position in the Yamaha music school, he shared the knowledge he had acquired at Berklee and has continued to teach the fundamentals of jazz to all kinds of people, from elementary school children upwards. For more than 20 years he ran a popular radio program, often introducing new music, Japanese and foreign, to listeners.

“On days when I don’t have a gig, I get up at around 5 a.m. and go for a walk,” he says, explaining his simple routine. “After breakfast, I doze off for a bit and then practice my saxophone for about two hours; I spend around an hour playing etudes and other pieces I have memorized and letting my mind wander… the tunes I want to create are not technically difficult. I try to use simple notes and melodies from my heart.”

Nabe-Sada clearly loves what he is doing, as his radiant smile testifies. It is the smile of a man who has lived a good life and still has much to give.