Book review of Alan Booth’s This Great Stage of Fools published in Japan Forward 16/4/2019

The best place to buy the book is directly from the publisher.

Alan Booth is best known as the author of The Roads to Sata, his account of a solo walk from the northern tip of Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s four main islands, to the southernmost cape in Kyushu. It took him four months of heavy trudging to cover the 2,000 miles.

Published in 1986, Sata was widely praised as a worthy addition to the distinguished line of British travel writing, as exemplified by the works of Freya Stark, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Graham Greene and other literary nomads.

Booth gave voices to the individuals he met on his journey, chronicling encounters with “businessmen, farmers, grandmothers, fishermen, housewives, shopkeepers, schoolchildren, soldiers, policemen, monks, priests, tourists, generals….. truck-drivers, Koreans, Americans, bar hostesses, professional wrestlers, government officials, hermits, drunks and tramps.”

In so doing, he uncovered an ura Nihon (“back side of Japan”) which is not geographical but social and psychological. He summarized his project in words he put into the mouth of an aged shop-keeper. “A country is like a sheet of paper: it’s got two sides. On one side there’s a lot of fancy lettering – that’s the bit that gets flaunted about in public. But there’s always a reverse side to a piece of paper, a side that might have ugly doodlings on it or graffiti.”

The place that fascinated him the most was Osorezan – “Terror Mountain” – a dark twin to photogenic Mount Fuji, located in the very north of Honshu, Japan’s main island.

Osorezan is the site of a primitive folk Buddhism centred on death and communication with the dead. With its scarlet Pond of Blood and mounds of stones built, supposedly, by the souls of children who died before they could repay their parents for giving them life, it evokes, for Booth, “a dusty, crouching terrible god who does not often reveal himself in the world.”

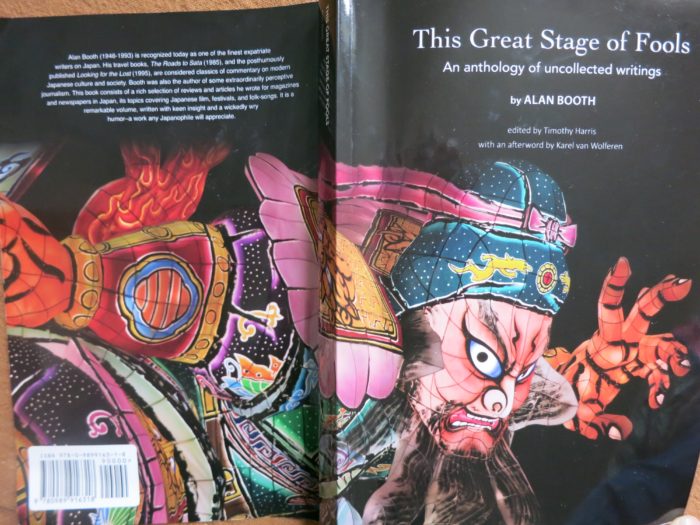

Booth did not publish another book in his lifetime; cancer killed him in 1993, at the age of forty seven. However, his friend Tim Harris has edited two posthumous works. Looking for the Lost, published in 1994, describes three further walks that Booth made. This Great Stage of Fools, published last year, is a collection of journalism, ranging from film reviews to a courageous and harrowing account of his final illness.

Both are well worth reading. Looking for the Lost is in many ways a more impressive achievement than The Roads to Sata, which is marred in places by a thin-skinned tetchiness of tone as Booth records his exasperation with what today’s campus radicals would term “micro-aggressions” – village kids yelling “Ziss is a pen” and “Gaijin, Gaijin”, inn-keepers questioning his ability to use chopsticks or eat sushi etc.

Annoying, perhaps, but if you travel through distant provinces it is no surprise that the people you meet tend to be somewhat, well, provincial. I experienced that aspect when I and a friend journeyed through “the backside of Japan” two years after Booth, taking six weeks to cycle the length of Honshu and unknowingly covering two thirds of his route. That said, most of the people we met were hospitable, interesting and remarkably generous, once the ice was broken.

Looking For the Lost is less judgmental and digs a lot deeper, not least into the author’s own psyche. The book benefits from a clearer structure, consisting of three walking trips in the steps of doomed historical figures – the decadent-school novelist Osamu Dazai, the samurai rebel Takamori Saigo and the Heike clan who were crushed by their rivals the Genji in the twelfth century. Dazai and Saigo killed themselves. The Heike disintegrated and the survivors were scattered to the winds.

Loss and lostness were attractive to Booth, which could be why he admired the “decayed grace” of the dingy towns of the Tsugaru plain, in the impoverished, storm-battered, snow-smothered north of Honshu. Never a true nomad, but rather a man in search of a home, Booth respected and perhaps envied rootedness. “They gave you the sense,” he writes of the northern towns, “of being in a place that was built to be lived in, not just passed through.”

This Great Stage of Fools is likewise more about Booth’s loves than his dissatisfactions. One of the strongest pieces is a homage to Chikusan Takahashi, the blind master of the Tsugaru shamisen. For Booth he was a totem of artistic integrity and creativity, rather as Mississippi bluesmen were for a generation of British musicians.

There is a fascinating series of essays on nine Japanese folk-songs and a similar series on fourteen Japanese festivals, from small local celebrations to the enormous four-day Bacchanalia that is the Awa Odori in Tokushima. Booth quotes some good advice from the Awa Odori festival song –

You’re a fool if you dance

You’re a fool if you watch the dancing

So you might as well dance.

At small festivals in Akita and Yamagata, Booth does join in, thumping the taiko drums and dancing himself into a frenzy.

Alan Booth arrived in Japan in 1970 at the age of twenty three. He had already made a name for himself as a promising theatre director. Indeed, as Tim Harris recounts in the foreword to This Great Stage of Fools, he became probably the first and last person to have vomited live on Belgian TV, after an over-enthusiastic celebration of winning the grand prize in a European students’ drama competition.

Although a prodigious drinker and, apparently, a world-class karaoke singer, skills that lubricated some of his on-the-road encounters, Booth was deeply serious about theatre, literature and the culture of Japan. That underlying seriousness, coupled with impressive background knowledge and insatiable curiosity, is the strength of his writing in all three books.

The world has changed a lot since Booth set off for Sata forty years ago. In retrospect, the 1980s boom in travel writing marked the peak of the genre.

Travel writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had been (usually) gentlemen of leisure, journeying through impoverished, little-known lands and recording what they saw, with varying degrees of empathy, for the benefit of a domestic readership with little opportunity to experience such exotic locales.

By the 1980s, travel had become much cheaper and more convenient and previously inaccessible lands were opening up. Colin Thubron wrote memorably about his long trip through China and Bruce Chatwin shot to literary celebrity on the strength of his adventures in South America and amongst the Australian aborigines.

Wanderlust, literary flair and an iron stomach seemed to offer, quite literally, a passport to bestseller-dom.

Since then, economic and political barriers to travel have continued to crumble, to the extent that travel to distant lands is possible not just for Western writers, but for their entire readerships as well. In today’s world of Google Earth, social media “bucket lists” and “gap year” students digging wells all over Africa and Asia, encountering “Remote People,” as Evelyn Waugh entitled one of his travel books, is no longer a privileged activity. .

Just as the gap between the writer and reader has shrunk, so has the gap between the writer and the written about, which was based on notions of economic and cultural supremacy which are increasingly under challenge. Perhaps the next masterpieces of travel literature will be written by citizens of Asian countries trekking through lesser known regions of Europe and finding much to appall and amuse them in their encounters with the natives.

Alan Booth, however, for all his emphasis on making his way on foot through a land largely unfamiliar to his readers, is more concerned with immersion in a culture, rather than passing through it – and this is especially true of the two posthumous books.

Even his outbursts of frustration and disappointment could be seen as a sign of commitment to and ownership of his Japanese experience. There is no metropolitan “centre” to which Booth will return after the journey is over, as was the case with part-time nomads like Waugh and Chatwin. He will die in Japan, where he spent nearly all his adult life.

At Osorezan, a blind medium told Booth that two hundred years previously he had been born a Japanese in a Tohoku town, but because of the sins he had committed in that life he had been reborn as a foreigner.

Perhaps in a time to come he will be reborn again in Tohoku.