Published in Nikkei Asia 12/11/2023

Olga V. Solovieva’s “The Russian Kurosawa” and David A. Conrad’s “Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan” link both famous and less well-known movies to contemporary events in Japan and the world that may have influenced them.

It has been 25 years since the death of the great film director Akira Kurosawa, yet interest in his work remains strong, and fresh insights continue to surface.

Two welcome additions to the critical studies on this renowned director are Olga V. Solovieva’s “The Russian Kurosawa” and David A. Conrad’s “Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan.” Both writers fruitfully explore how Kurosawa’s films, including samurai epics, reflect the condition of Japan when they were made.

Solovieva, a comparative literature specialist at the University of Chicago, analyses Kurosawa’s obsession with Russia, evident in several films, his autobiography and many comments made over the years. The Russia that entranced Kurosawa was not the expansionary state that fought a brutal war with Japan in 1904-1905, let alone the Soviet Union of Lenin and Stalin. It was not a place at all, but a humane literary culture constructed by a remarkable series of writers and thinkers.

In the early decades of the 20th century, Russian literature dominated the field of foreign literature in Japan. Kurosawa claimed to have read Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” 30 times and considered Fyodor Dostoevsky his favorite author. Of his films, the following are adapted from or partially inspired by Russian sources: “The Idiot” (1951, from Dostoevsky), “Ikiru” (1952, from Tolstoy), “The Lower Depths” (1955, from Maxim Gorky), “Red Beard” (1965, from Dostoevsky) and “Dersu Uzula” (1975, from Vladimir Arsenyev).

From “Ikiru”

Solovieva is a highly creative interpreter of Kurosawa’s work, occasionally excessively so, but her thorough knowledge of the source material sheds valuable new light on Kurosawa’s choices. Particularly impressive is her analysis of “The Idiot,” a little-discussed film that was severely cut by the studio, much to the director’s indignation. Sadly, the full-length version has been lost, but many powerful scenes remain, featuring bravura performances by Toshiro Mifune, Setsuko Hara and Masamune Mori, playing the members of the doomed love triangle. Properly presented, it could have been an all-time classic.

The author zeroes in on the backstory that Kurosawa puts together for Kameda, the epileptic “idiot” of the title. Mistaken for a war criminal, he was about to be executed by a firing squad when the Americans realized they had the wrong man. Apparently, such mix-ups were far from uncommon. Now he is returning to his Hokkaido home from Okinawa, where he was confined to a mental hospital.

Mifune with Setsuko Hara, murderer and murderee

The implication is that Kameda was stationed in Okinawa and participated in the horrific scenes of death, destruction and forced suicide there in the summer of 1945. This backdrop of collective war trauma differentiates the film greatly from Dostoevsky’s original.

The long shadow of Japan’s lost war lingers in other films. Solovieva believes that Kurosawa’s preceding film, “Rashomon” (1950), with its alternative narratives of guilt, may owe something to the 1946-1948 Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, which tried 28 Japanese military and political leaders for alleged war crimes. “The Lower Depths” (1957), she points out, is nominally set in Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1867), but the mise-en-scene includes a strand of barbed wire. Given Kurosawa’s minute attention to every detail of his sets, whether visible or not, that had to be reference to contemporary reality in Gorky’ story of down-and-outs living in squalor. As late as the 1970s, disabled veterans could be seen begging for alms in urban centers.

That the war experience remained an important issue for Kurosawa is obvious from “The Tunnel,” by far the strongest of the short films that make up the omnibus piece “Dreams” (1990). In a dynamic enactment of war memory, it gives us an undead platoon of soldiers marching back to our world from the caverns of oblivion.

The women demand to be given as much work as the men

More controversially, Solovieva hypothesizes that in his post-war films Kurosawa reverted to a Tolstoyan antiwar stance to atone for the propaganda film, “The Most Beautiful” (1944), that he made at the behest of the military government. There may be something to that, but Kurosawa’s propaganda effort was mild stuff compared to the racist iconography often employed by the Americans, let alone the Hitler-worship of the German director Leni Riefenstahl, to whom the author unfairly compares him.

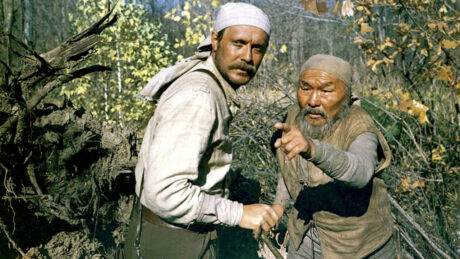

“Dersu Uzala,” Kurosawa’s comeback film after a long period of financial problems, receives a fresh and convincing explication from Solovieva, well backed by historical Russian language sources. At the age of 65, the great director spent a year in the harsh conditions of the Soviet Far East, having been bankrolled by the USSR production outfit, Mosfilm. The film he chose to make was an adaptation of a memoir that was little known in the West but had fascinated the Russophile Kurosawa for decades.

On the face of it, the story of a Russian officer’s friendship with a simple nomadic hunter from the Goldi ethnic minority in the early years of the 20th century is an apolitical meditation on changing times. As Solovieva shows, that could never have been the case. Consciously or unconsciously, Kurosawa was telling a story of the clash of empires and the destruction of the cultures of minority groups.

Arseneyev and Dersu in the taiga

Arsenyev, the soldier who wrote the memoir on which the film is based, met Dersu and hired him as a guide when he was conducting a survey that would prepare the way for expansion of the Russian empire. Earlier in his career, Arsenyev had taken part in pacification campaigns for which he was decorated, though he never mentioned them subsequently. Solovieva quotes the great Russian dramatist Anton Chekov, who journeyed through the Russian Far East, describing Russian settlers and the military killing native people “like animals.”

Kurosawa would have known that the timespan of the events described took in the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War, a decisive step in Japan’s own ambitions of empire; that Japanese troops operating as part of an Allied Expeditionary Force occupied parts of the Russian Far East from 1918 to 1922; that Arsenyev was considered “pro-Japan” by the Soviet authorities and died in disgrace; that his widow was shot as a Japanese spy after a trial that lasted 10 minutes and his daughter was sent to the gulag for 10 years; and that the Soviet army crossed the Ussuri region, Dersu’s home ground, when Moscow unilaterally abrogated a peace treaty with Japan and stormed into Japan-controlled Manchuria in August 1945, ultimately taking some 600,000 military and civilian prisoners to camps in Siberia from which some never returned.

In the harsh conditions of the taiga (northern snow forest), the tall, pale-skinned Arsenyev is the pupil and Dersu, with his squat build and broad Oriental features, is the master. One lesson that he delivers is that travelers should leave some of their food and fuel behind in shelters they have used to benefit unknown others. Solovieva connects this custom with the “mutual aid” theories of Peter Kropotkin that were highly influential in Japanese anarchist circles in the early 20th century. Did Kurosawa know them and find them appealing?

The richness of Solovieva’s approach lies in the literary connections she makes. David A. Conrad sees Kurosawa through the eyes of a Japan specialist, examining all 30 of the films in chronological order and commenting on contemporary events in Japan and the world that may have influenced them.

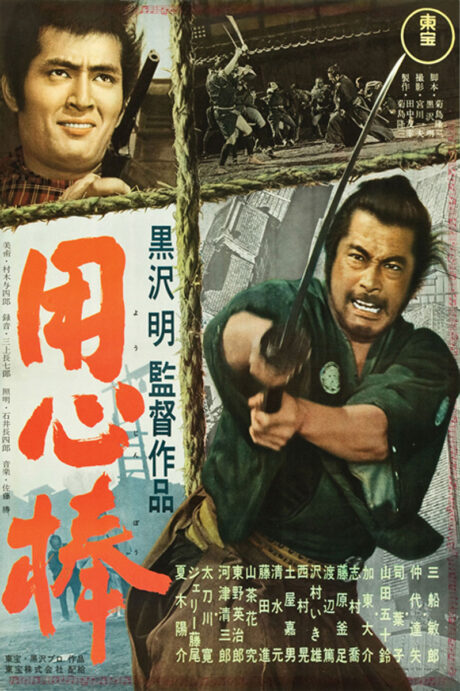

Like Solovieva, he sometimes uses imaginative projection to give new meanings to the films. For example, he associates the supercool samurai memorably played by Mifune in “Yojimbo” (1961) with the nonaligned movement which held its first conference in the year of the film’s release. Just as the nonaligned countries sought to take a neutral stance in the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, so Mifune’s nameless hero views the film’s two rival gangs with equal contempt.

Yojimbo poster

Likewise, Conrad offers an unusual perspective on “The Hidden Fortress” (1958), an upbeat and entertaining film to which George Lucas paid tribute in the original “Star Wars” (1977). When the Kurosawa film appeared, Japan was well into its post-war recovery, and tourism and sightseeing were all the rage — part of a reassessment of Japanese traditions after the shock of defeat and occupation started to fade. Kurosawa pitches in with a long climactic sequence featuring a fire festival, an age-old ceremony, as well as many scenes of great natural beauty. The dappled light of the forest is sparkling and magical, not sinister, as in “Rashomon.”

The plot, later borrowed by Lucas, concerns the secret journey of a young princess to take up her rightful position on the throne of her country. Conrad links her with a real Japanese princess-to-be who was also on a journey at the time the film was made. Michiko Shoda was the modern-minded daughter of the CEO of a flour milling company. She met the emperor of Japan’s son on a tennis court and became engaged to him soon after. Their marriage in 1958 was televised and half a million people followed the wedding procession. In 1989, Princess Michiko became become Empress Consort when her husband succeeded his father as emperor.

One of the strengths of Conrad’s book is that he gives as much attention to the more obscure items in Kurosawa’s filmography as to the celebrated masterpieces. His verdict on “The Most Beautiful” is more generous than Solovieva’s: “emotional complexity gives it a staying power that propaganda rarely retains after its historical moment has passed.” He also writes perceptively about “Sanshiro Sugata” (1943) and the entertaining but often maligned “Sanshiro Sugata Part Two” (1945), two martial arts films that helped pave the way to the era of Bruce Lee.

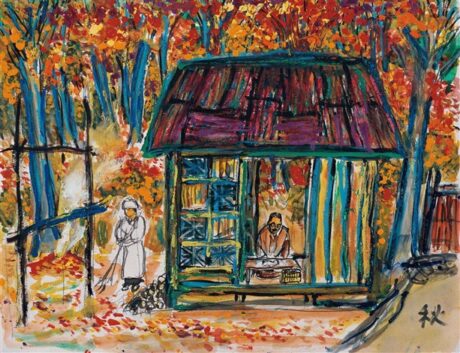

Most impressive, though, is his analysis of the maestro’s last film, “Madadayo” (1993). Kurosawa is often said to be the “least Japanese” of the prominent Japanese directors, but his swansong was squarely aimed at his domestic audience. Foreigners may find it difficult to understand the long-lasting relationship between a cat-loving writer and his former students.

Kurosawa’s sketch of the teacher’s house

Little happens, even in the war years and the occupation, which are treated with unusual lightness. The characters drink beer, they laugh, they get older. The only tension comes when a cat goes missing. But that is exactly the point of this gentle meditation on mortality, the inevitability of change and what it means to have a good life.

Madadayo, meaning “not ready”, is the call in a children’s game of hide-and-seek, but here it means “not ready” to give up on friendship, the glories of nature and the joy of existing in this transient world in which we find ourselves.

Conrad sums it up superbly. “The old man remembers an idyllic scene from his childhood. ‘Madadayo’ says a boy as he gazes into the blazing sky that changes from pink and yellow to blue and green and finally to gold. Just off camera, Kurosawa sat motionless while the final scene of his career played out in front of him. After a period of silence, he announced ‘cut’ then stood and walked away.”