Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 14/11/2018

As a confirmed film buff and long-term fan of the work of Akira Kurosawa, I was delighted to see the results of the BBC’s recent ranking of the greatest foreign-language (that is, non-English) films of all time. The top five selections included three Japanese films, two of them directed by Kurosawa.

1. Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954)

2. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio de Sica, 1948)

3. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

4. Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

5. The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1938)

The sweep and diversity of the survey gives it more credibility than most such exercises. A roster of 209 prominent film critics from 43 different countries were asked to list their 10 favourite films. Rather than restricting the survey to Western pundits, the BBC spread the net wider, with North Americans and Western Europeans making up less than half of the “electorate,” and female critics accounting for 45%.

If the methodology is in line with changing global realities, so are the results. One quarter of the top 100 films are East Asian in origin – with 11 from Japan, six from China, four from Taiwan, three from Hong Kong and one from South Korea. If you narrow the focus to films made in the last 30 years, six of the top 10 are East Asian – one each from South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and China and two from Taiwan.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out that different regions have different cinematic preferences. East Asian critics tend to favour East Asian films and have less enthusiasm for inward-looking European masters such as François Truffaut and Ingmar Bergman. On the other hand, Kurosawa seems to be well-appreciated everywhere, with two more of his films — Ikiru (1955) and Ran (1985) — also appearing in the BBC ranking.

There is, however, one part of the world where the Kurosawa oeuvre appears to be less highly esteemed. That is in Japan itself. Of the six Japanese critics who participated, not one chose a Kurosawa film. This is not out of some misplaced sense of national modesty. One Japanese critic listed six Japanese films in her top 10, but found no room for anything by Kurosawa. Another did nominate a Kurosawa film – one by contemporary director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, best known for his grisly thrillers, rather than the more celebrated Akira.

The contrast with Chinese critics is remarkable. Out of the 21 surveyed, 16 included an Akira Kurosawa film in their selections. Such is the respect for Kurosawa in China that production company Jinke Entertainment has bought the rights to his unfilmed screenplays. A Taiwanese version of Rashomon is also under development.

The truth is that Kurosawa, who died 20 years ago this year, has always had a complicated reputation in his own country. Not for nothing do the media often write his name in the katakana syllabary reserved for foreign loan-words. By winning the Golden Lion prize for Rashomon at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, Kurosawa became famous internationally before achieving prominence at home, thus overshadowing his “senpai” (seniors), Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. From 1965 onwards, Japanese studios refused to back his projects financially, forcing him to raise money from foreign sources.

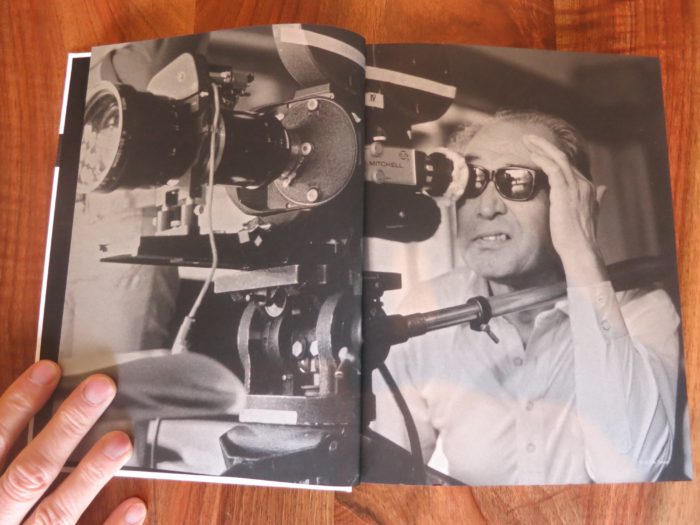

The idea that Kurosawa is not fully Japanese derives both from his persona and his works. Unusually tall for a Japanese of his generation, he could be autocratic and wilful, hence the nickname of “the Emperor.” Although he created the modern samurai film, his work rarely explores intricate Japanese social codes in the manner of Ozu and Mizoguchi. Instead, the Kurosawa world is mythic and universal. That is why foreign remakes of his films, such as The Magnificent Seven (1960), have proved so popular and why Kurosawa was able to “samuraize” Shakespeare so successfully in Throne of Blood (1957), based on Macbeth, and Ran, based on King Lear.

Perhaps it is this universality that turns off Japanese critics looking for familiar cultural context while attracting film-lovers in Colombia, Turkey, Singapore, South Africa, Belgium and elsewhere.

In today’s world of fake news and competing historical narratives, Rashomon, with its multiple perspectives on the same bloody event, is more relevant than ever. Likewise, the kind of epic struggle depicted in Seven Samurai dates back eons in both Eastern and Western cultures. The film will continue to thrill as long as against-the-odds battles remain to be fought, which is to say as long as human nature remains as it is.

Rankings are inherently subjective and people can argue about them all day long. What is indisputable is that great films travel far through time and place. When viewed by fresh eyes, they become new films.

I know that from personal experience. If it had not been for an encounter with the Seven Samurai at a university film club on a rainy night many decades ago, I doubt that I would have come to spend the greater part of my career in Japan. I can honestly say Kurosawa changed my life.