Published in the Nikkei Asian Review 23/4/2019

Turning Japanese was a 1981 hit by a UK pub-rock band called The Vapors. According to the lead singer, the title means “turning into something you didn’t expect to.” In the financial markets, the phrase has become short-hand for an extended period of economic stagnation, on the lines of the “two lost decades” that followed on from the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in 1990.

As with the lyrics of the song, the initial idea was that the phenomenon – also known as ”Japanization” and “Japanification” – was bizarre and highly unlikely to occur in Western countries.

No longer. Low growth and rock bottom interest rates have characterized the economic landscape in much of the developed world since the global financial crisis of 2008.

This year, disappointing data in Europe has set off another round of “turning Japanese” warnings from major finance houses such as Pimco, Societe General SA and Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Dutch bank ING has even developed an index that purports to measure “the risk of the Japanese disease.” Based on research by Professor Takatoshi Ito of Columbia University, it blends such factors as GDP growth, inflation, interest rates and demographic change.

So Japan the outlier has become Japan the precedent or frontrunner. At the turn of the century, German 10-year government bonds yielded 3.5% more than the Japanese equivalent. Now Japanese and German yields have converged in negative territory. Demographics are also not very different. Indeed, Japan’s total fertility rate is higher than the rates for several European countries, including, depending on the year and the source, Portugal, Poland, Spain, Greece, Italy and Germany.

There are however some significant differences – and they are not in Europe’s favour. Japan never experienced the disastrous mass unemployment that afflicted much of southern Europe. Even after several years of recovery, youth unemployment in Spain remains at 38%. Italy’s GDP is no larger now than it was in 2004, making it a rare example of a country that has had a bust without experiencing a preceding boom.

On the other side of the ledger, Germany’s current account surplus stands at an extraordinary 7.5% of GDP, twice the size of the imbalances that triggered the drastic managed appreciation of the Deutschemark and the yen in the mid-1980s.

Not coincidentally, these countries are all members of the Eurozone, which means that adjustment by currency depreciation – which worked wonders for distressed Asian countries in the aftermath of the late 1990s crisis – is not an option.

One-size-fits-all monetary policy and constraints on fiscal policy rule out other standard policy tools. As with the gold standard in the 1930s, membership of the euro has an inherent deflationary bias. Deficit countries in southern Europe have been forced to retrench, but there is no offsetting pressure on surplus countries like Germany to increase demand.

With the Brexit saga hogging the newsflow, the structural flaws of the euro project have become less topical, yet they will continue to pose serious risks to economic and political stability well after Britain’s relationship with the EU is settled.

Economic logic requires the Eurozone to morph into a single state with fiscal transfers from richer to poorer areas. Politics makes that impossible for the foreseeable future. The next significant recession could spark off a chain reaction of rising unemployment, populist rage and street violence that would make the recent “gilets jaunes” protests in France look mild.

Talk of the “Japanification” of Europe is doubly misleading because Japan today is not the stagnant and deflationary Japan of 1997 or 2010. The current economic expansion is, at 72 months old, on the cusp of becoming the longest since the war. During that period, employment has soared to unprecedented levels and business investment has risen to the highest share of GDP in a quarter of a century.

As noted in a recent speech by Yutaka Harada, one of the “doves” on the Bank of Japan’s Monetary Policy Board, better economic conditions have been accompanied by improvements in several indicators of well-being. He cites the declines in suicide, personal and regional inequality, relative poverty of children and single parent households, also the slight uptick in the marriage and fertility rates.

Japan’s new openness towards immigrant workers and free trade initiatives, such as the Trans Pacific Partnership, which it now effectively leads, is also a product of the confidence that comes from a drum-tight labour market and a highly profitable corporate sector. The same could be said for domestic political stability: Prime Minister Abe’s comfortable support rates continue to protect him from the kind of storms that assail his peers in Europe and North America.

Japan managed to shake off its long malaise via large-scale monetary easing, currency depreciation and some well-timed regulatory tweaks. Visa restrictions for foreign tourists were eased and inflows of temporary foreign workers encouraged and stock market practices improved. The recent hostile takeover of sportswear producer Descente by blue chip trading house Itochu is an example of change in corporate behaviour.

If all this constitutes “turning Japanese,” it does not sound too bad at all. Two decades of “turning European,” on the other hand, could prove disastrous. I really think so.

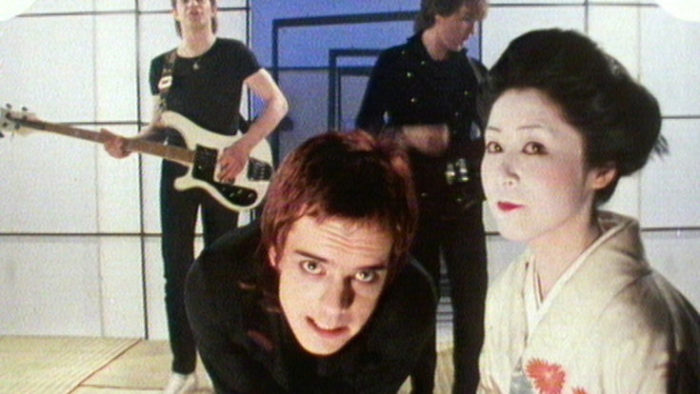

From Takashi Murakami’s short film “Akihabara Majokko Princess,” as featured in the Pop Life exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2009.